Patriarchy is alive and well throughout the world. But the English-language media flatters itself by one-sidedly portraying machismo as a particularly Latin American malady, all the while overlooking significant feminist gains made in the region.

Take, for instance, the entry under “machismo” in the latest edition of Britannica which asserts: “It has for centuries been a strong current in Latin American politics and society.” But the encyclopedia makes no such recognition for its own Anglo society.

An article in the AP on sexual bias in Mexico blames “Mexico’s ‘machismo’ culture and strong Catholic roots,” calling out patriarchy as a defining and harmful feature for the whole of Latin American culture.

Citing the attacks on feminism by the ultra-right president of Argentina, Javier Milei, The Guardian generalizes, how misogyny is “a very serious problem for Latin America.” The article continues: “Of course, Latin women continue to learn from those in the west,” implying that benighted Latinas should take tips from their more enlightened western sisters. The article concludes: “Women in Latin America need women in the west to work with us to put an end to this violent oppression.”

In a worldwide report on last International Women’s Day, Al Jazeera first highlighted Latin America with the examples of Argentina, Ecuador, and Bolivia as places plagued by gendered violence and only then added: “In many European countries, women also protested against violence.”

Verywell Mind, a US-based health website, targets “Latino culture” as patriarchal. They report on “generations of women who live or grew up in Latin American and immigrated to the United States truly believing that their happiness depends on a man.”

The Washington Post, describing Mexico as a “bastion of machismo,” marveled how it got their first woman president before the US.

Mexico

Feminists celebrated Claudia Sheinbaum’s electoral victory in June 2024, making her the first female to accede to the presidency in Mexico. However, had she lost to the nearest runner-up, Xóchitl Gálvez, Mexico would still have had its first woman as chief of state. Gender was simply not an issue in the contest, with both main challengers female.

Digging deeper into the stereotype of Latin American machismo, we see that Mexico having women as the top two contenders for the presidency is notable but not anomalous. In fact, women have held presidencies in several Latin American countries over the past half century.

Most Latin American countries have been influenced by the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women. This international treaty was adopted in 1979 by the UN General Assembly and unanimously ratified or adhered to by all of the Americas with the notable exception of the US, which signed but did not ratify it.

That international treaty had been catalyzed by Mexico, which held the World Conference on Women back in 1975. Marking a significant moment in the global movement for gender equality, this UN meeting was the first to focus exclusively on women’s rights and equality. It produced the World Plan of Action for legal and institutional reforms to combat discrimination against women.

Some revealing comparative statistics reflect differences in the social realities in the US and in Mexico. For example, as of 2025, Mexico achieved gender parity in both chambers of its national legislature. In comparison, women hold only 29% of the House seats and 26% of the Senate in the US.

Since 2014, Mexico has constitutionally mandated gender parity in candidacies for federal and local legislative elections. Going back further to the Mexican Revolution, there were literally thousands of soldaderas, female combatants. And even further back, women held leadership roles among the Zapotecs, Mixtecs, and Maya.

Fast forward to June 1, Mexico popularly elected five women and four men to their 9-person supreme court, consistent with the 2019 constitutional reform known as paridad en todo (parity in everything).

Electoral gender parity

Mexico is not alone in promoting electoral gender parity. A number of other countries in Latin America has established “gender quotas” in electoral lists. The gender quota is 50% in Bolivia, Costa Rica, Ecuador, Mexico, Nicaragua, Peru, Panama, and Venezuela. Honduras, El Salvador, Haiti, and Paraguay have lesser quotas. However, lax enforcement and loopholes to circumvent them continue.

Cuba does not have mandatory statutory gender electoral quotas. Rather, the socialist country has a strong commitment to equity, where its Communist Party promotes women, youth, and racial minorities. Fully 56% of its national assembly is composed of women.

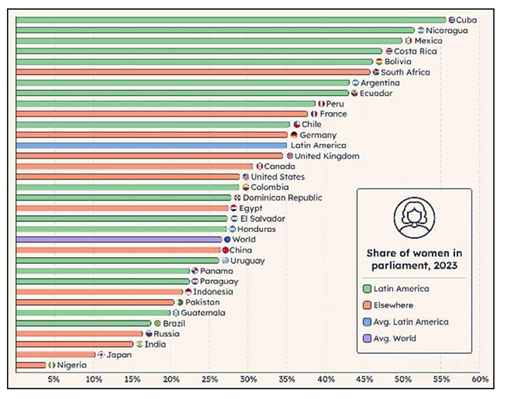

A recently published chart (below) from Latinometrics shows that Cuba, Nicaragua and Mexico are indeed the leaders in female parliamentary representation, not only regionally but globally.

Contrary to what the English-language media’s hype about machismo would have you believe, Latin America has made great strides in gender equality in recent years and now leads the world in female political representation.

Nicaragua

“Women are not fighting for space anymore,” declares Nicaraguan National Assembly Deputy Flor Avellán. “Now we have that space and we are empowered every day.”

Nicaragua may be one of the region’s smallest nations and came just 19th out of 23 Latin American countries in a recent “prosperity” ranking, but it is one of the leaders in establishing the role of women in public life. Just last year it was judged by the World Economic Forum (WEF) to be sixth in its global index for closing the gender gap. This was the highest in the region (WEF does not include Cuba) and was higher than many “developed” countries such as the US and UK.

Since that index was compiled, Nicaragua has taken a further step in creating a unique male/female co-presidency. Nevertheless, and with little explanation, the 2025 gender gap index dropped Nicaragua from sixth to 18th, putting it third in the region, behind Barbados and Costa Rica. This may be because metrics used by bodies such as the WEF are rooted in first-world metric inapplicable to Nicaragua. For example, firms with female majority ownership and female top managers are metrics, but there is no metric for women running their own businesses, let alone micro-businesses, which is Nicaragua’s strength.

Nicaragua is ranked first in parliament and in political institutions by the WEF, achieving parity between male and female representatives. The 2012 law requiring this was initially met with hostility from some men. But now it has become accepted as successful: “having so many women in leading positions has changed the culture,” according to Nicaraguan feminist Abigail Espinoza (pers.com). Nicaragua’s unique approach mandates 50% female leadership at all levels – from city council to municipal leaders to parliament and right up to the presidency.

Empowering women is seen not only in terms of political participation, but as a multidimensional process to achieve societal change, and in particular to improve women’s daily circumstances. There are many instances of this.

For example, over 23,400 small businesses have been formalized in 15 years, the majority owned by women; over 500 new women’s cooperatives have been formed. The “Zero Hunger” program has significantly improved women’s earnings. The program provides livestock, seeds, fertilizers, and building materials to women in rural areas, benefitting one in every six families in the country. Contributing to the nation’s food sovereignty, Nicaragua now produces 90% of the food it consumes.

In the field of health, maternal deaths have fallen by almost 80%, while infant mortality dropped by 58% between 2006 and 2024. Credit is due to the government’s massive extension of health services; specifically the establishment of 201 casas maternas, where women can go in the weeks immediately prior to giving birth.

Until recently, Nicaragua had the highest teen pregnancy rate in the region. Now most Nicaraguan women are having their first child at age 27, and Nicaragua ranks number one in the world for educational attainment for women and girls. Those young women who do get pregnant now have many options for continuing their education while also raising their child.

Violence against women remains a problem, but Nicaragua has reduced its incidence to the lowest in Central America, having established more than 400 women’s police commissions where only female police officers (40% of the national force) attend women and children exclusively. They even make home visits to identify and help resolve domestic abuse. Nicaragua has passed laws against femicide and violence against women, allowing for stricter sentencing and swifter justice.

The feminist movement in Nicaragua, mobilized mainly through the Sandinista National Liberation Front, is a class-based feminism that fights not only against patriarchy but also for an anti-imperialist and socialist class consciousness.

Nicaragua’s “National Plan to Combat Poverty and Promote Human Development 2022-2026” is fundamental to this goal. Its detailed programs, backed by nearly 60% of the national budget, aim to establish women’s rights by guaranteeing access to free, quality education at all levels and in all modalities, access to health care, access to the means and forms of production, and food security. Reduction of poverty and inequality is therefore seen as absolutely key to women’s empowerment.

The geopolitics of machismo

To characterize Latino machismo as mythic is in no way intended to suggest that it does not have a basis in reality; it does. Despite achievements, Latin America still has a long way to go to end patriarchy.

For instance, femicide, the intentional killing of women or girls because of their gender, has been identified as a particular abomination in Guatemala, El Salvador, and Honduras, where “incredibly high rates” prevail. It is no coincidence that this gendered form of viciousness is found in societies that suffered from the US-backed dirty wars in the 1980s and onward, which left a culture of impunity. Guatemala and El Salvador were targets of counter insurgencies and Honduras was a base of operations. Conversely, revolutionary Cuba, followed by Chile and Nicaragua, has the lowest rate of femicide.

Progressive administrations in Mexico, Honduras, Cuba, Venezuela, and Nicaragua have launched campaigns against machismo. Reactionary administrations, such as El Salvador and Argentina – both fully backed by the US – are dismantling feminist advances.

Regionally, feminist gains are being advanced under progressive administrations pursuing greater independence from the US. In contrast, reactionary, Washington-aligned regimes are actively rolling back those gains. As a result, the struggle against machismo in Latin America cannot be separated from the broader struggle against imperialism.

This dynamic helps explain why feminist advances in countries like Cuba, Mexico, and Nicaragua are often ignored by corporate media – or when acknowledged, are reduced to the actions of individual leaders like President Sheinbaum. What is overlooked is the broader social transformation taking place – one that challenges patriarchal norms and offers a model from which others might learn. Once again, it is the “threat of a good example”– this time led by women.

The post Challenging the Media Myth of Latino Machismo first appeared on Dissident Voice.

This content originally appeared on Dissident Voice and was authored by Roger D. Harris, Becca Renk, and John Perry.