Angolan journalist and lawyer Teixeira Cândido wants to know who targeted him with spyware, and he wants justice.

“First and foremost, we must seek to find out who the entities are that have acquired these spyware tools,” Cândido told CPJ, as findings published by Amnesty International’s Security Lab show that a malicious link sent in a WhatsApp message infected his phone with Predator spyware.

The commercially available spyware can provide access to an infected device’s microphone, camera, and data, including contacts, messages, photos, and videos, without the user’s knowledge.

Amnesty, the University of Toronto’s Citizen Lab, and U.S.-based cybersecurity firm Recorded Future have previously documented infrastructure for operating Predator in more than a dozen countries, including Angola. But this marks the first publicly known case of spyware targeting in the country, where restrictions on the press have tightened ahead of elections in August 2027.

The detection of Predator on Cândido’s phone reveals how powerful surveillance technology has been wielded against Angola’s press and civil society, alongside repressive laws and other forms of intimidation.

“I literally felt naked! It’s as if someone I don’t know had stripped me naked in public. It’s like taking a shower with people watching. That’s how it feels,” Cândido told CPJ during an interview in Luanda, Angola’s capital. “I don’t know what kind of information they had access to. I don’t know to what extent they shared my intimate conversations.”

Russian editor Galina Timchenko similarly described feeling “naked in the street” after being targeted with Pegasus spyware sold by Israel-based NSO Group.

Malicious links

Forensic traces prove that Cândido received a link on May 3, 2024 — ironically, World Press Freedom Day — and likely clicked on it, resulting in Predator installing on his phone the next day. The infection lasted less than 24 hours and was removed when Cândido restarted his device. The attacker sent more malicious links over the following weeks but these appear not to have resulted in additional infections, likely because he did not click them, Amnesty reported.

Identified in collaboration with human rights groups Friends of Angola and Front Line Defenders, Amnesty’s findings do not reveal who ordered the surveillance.

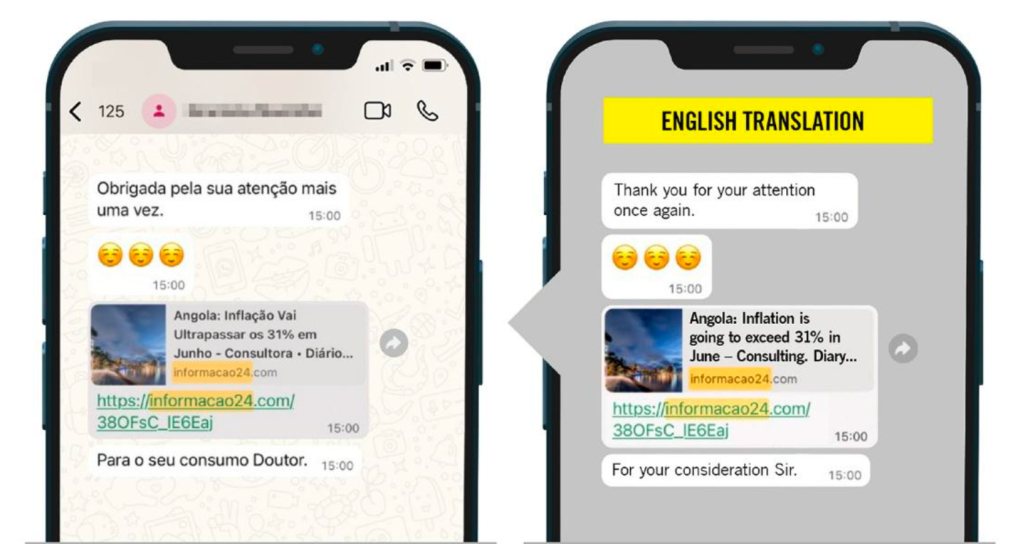

“This was a typical one-click attack,” said Carolina Rocha da Silva, Operations Manager at Amnesty International’s Security Lab, which has been tracking Predator for several years. “The sender was using an Angolan phone number, a traditional Angolan name, and had a story, a motive for reaching out.”

The WhatsApp message came from someone purporting to represent Angolan students interested in talking to Cândido about socioeconomic development, Amnesty said.

Predator was developed by the Intellexa Consortium, an international network of companies selling surveillance services, founded by former Israeli military officer Tal Dilian.

The “Intellexa Leaks” reported in December 2025 suggest that staff of the company may have access to parts of their clients’ Predator systems, including the ability to view data gathered from spyware targets.

Dilian did not respond to CPJ’s request for comment via email.

In a response to the December leaks investigation, Dilian’s lawyer said, “Companies seeking export licences [for active cyber-tools] must take responsibility before selling a system, while governments bear full responsibility for their use after purchase.”

Democracy under strain

Spyware poses an existential threat to press freedom — menacing journalists’ physical, digital, and psychological safety, and undermining their crucial role in democracy.

“It’s really a matter of personal safety. You don’t know if you’re being watched, if you’re being followed,” Cândido said, describing how the attack affected him. “Despite all the security measures you can take, there’s always a feeling of insecurity that doesn’t go away.”

Cândido told CPJ he started to worry about digital surveillance around Angola’s 2022 national election, after repeated burglaries at the headquarters of the Syndicate of Angolan Journalists, which he headed until 2024.

“They only stole computers and weren’t interested in anything else,” he said. “The fact that they took our computers made us aware of the interest in our documents and contacts, and it would be natural for them to also be interested in our phones.”

As a host with the privately owned Radio Essencial broadcaster, Cândido is a prominent Angolan media figure, often critical of authorities. But he suspects the spyware attack was prompted by his work as a union leader and fierce advocacy for press freedom.

‘Draconian laws’

Angola transitioned from communism to democracy in 1992, Florindo Chivucute, executive director of Friends of Angola, told CPJ. But a wave of “draconian laws” introduced during President João Lourenço’s second term, which began in 2022, have set the country back.

“He managed to undo the steps that we have made in terms of creating institutions and guaranteeing certain freedoms,” Chivucute said. “Now it’s fair to say … Angola is an authoritarian regime.”

CPJ has for years documented Angolan authorities’ prosecution of journalists on criminal defamation and insult charges, as well as broadcast suspensions and other forms of harassment.

In 2024, Angola passed the National Security Law, giving security organs powers to disrupt telecom and internet systems under “exceptional circumstances.” The same year, a law on vandalism made it a crime to film, photograph, or publish information relating to the security of law enforcement and other public services, although much of the law has been declared unconstitutional.

Already in 2026, parliament has advanced two more draft laws: one would criminalize sharing “false information” and a second on cybersecurity would expand surveillance powers with limited oversight, which Cândido worries would promote fear among citizens.

“Only judges can authorize [wiretaps] … and only when there is suspicion that the person has committed a crime,” Cândido said of the current law. “I am a journalist, I am a lawyer. I don’t know to what extent there could be an order of this kind.”

But the proposed cybersecurity legislation would create a National Cybersecurity Centre with “regulatory, supervisory, inspection, and sanctioning functions.” This would include the ability to demand information deemed “against state security” from communications operators, such as internet providers, without a court order.

Responding to CPJ’s request for comment about spyware targeting in Angola, Alvaro João, spokesperson of the General Prosecutor’s Office, said his office “always tries to act within the limits of the law and has no knowledge of such situations.” Luis Fernando, spokesperson for the presidency, similarly told CPJ that he had no knowledge of any proof of spyware use. In response to CPJ’s questions via messaging app, Ministry of Interior spokesperson Wilson dos Santos said he would be able to comment when details of the attack had been made public.

In pursuit of accountability

Litigation is one avenue for responding to spyware abuses.

In January, a U.K. high court ordered Saudi Arabia to pay over 3 million British pounds (US$4 million) in damages to London-based dissident Ghanem al-Masarir, whose phones were targeted with Pegasus. A California judge in 2025 also ordered NSO Group to stop targeting WhatsApp users with Pegasus and to pay damages, while a trial is ongoing in Greece over the targeting of journalist Thanasis Koukakis with Predator.

Cândido said he hoped for accountability within Angola, but called for international support to reveal those behind surveillance abuses. CPJ continues to call for governments to curb spyware attacks.

In 2023, the U.S. added Intellexa firms to an Entity List, which restricted their ability to do business with U.S. companies for “engaging in activities contrary to the national security or foreign policy interests.” Then, in 2024, the U.S. sanctioned Dilian and more Intellexa-linked individuals and firms.

But in December 2025, three of those individuals were removed from the sanctions list, triggering questions from human rights experts and lawmakers. On February 13, five U.S. Congress members wrote to the Treasury Department and the State Department expressing “deep concern” and requesting a briefing by February 27 “to ensure Congress understands the Administration’s justifications for these delistings.”

The U.S. Treasury Department, which announced the sanctions removals, did not immediately respond to CPJ’s emailed request for comment.

“Surveillance ultimately threatens our professional activity. We must unite and create a large international network, even against states, if necessary, to raise awareness, because it must be possible to defend freedom,” Cândido told CPJ.

“Otherwise, one day we will wake up and there will be no more journalism!”

This content originally appeared on Committee to Protect Journalists and was authored by Jonathan Rozen.