Janine Jackson interviewed Dedrick Asante-Muhammad, president of the Joint Center for Political and Economic Studies, about State of the Dream 2026 for the January 23, 2026, episode of CounterSpin. This is a lightly edited transcript.

Janine Jackson: Media’s insistence that there’s something called “the economy,” that can be doing well or poorly, actively obscures the fact that we are differently situated, and what’s good news for some may mean nothing, or worse, for others. Economic news could be presented, not just in terms of different impacts on different people, but in relation to where we want to go, as a society that has yet to rectify grievous historical and structural harms.

That’s why you can appreciate the framing of a new report on the economic and social well-being of Black Americans, released on Martin Luther King Day, entitled State of the Dream 2026. It’s a status update, because we’re supposed to be going somewhere. It may feel new now—and these times are weirdly special–but holding the vision of racial equity in this country has always been hard, because powerful people have always been set to roadblock the effort, and even to reverse its course.

Joint Center for Political and Economic Studies (1/19/26)

The report—a diagnosis and a call to action—is a collaborative effort spearheaded by the Joint Center for Political and Economic Studies. We’re joined now by the president of the Joint Center, Dedrick Asante-Muhammad. Welcome back to CounterSpin, Dedrick Asante-Muhammad.

Dedrick Asante-Muhammad: Thanks for having me.

JJ: The report goes beyond economic issues per se, but those issues are central. The full title is State of the Dream 2026: From Regression to Signs of a Black Recession. So let’s start there. What stands out in the economic data that you looked at?

DA: What stands out is always, too, what could be measured. I think one challenge is:, the policy change that occurred in 2025, it’s hard to get good analysis, good data, until a year, two, three afterwards, right?

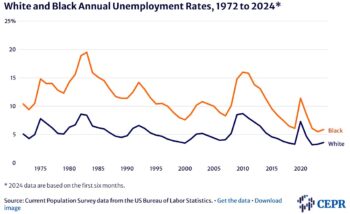

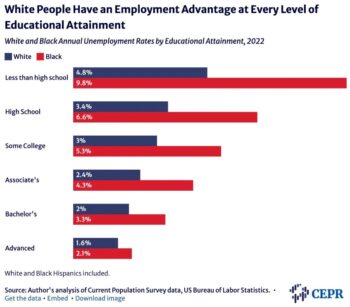

So, the things that are most regularly measured are things like unemployment. And that was something that really stood out to me, is that during Trump’s first administration, Black unemployment actually went down about 0.8%. But in 2025, we saw Black unemployment increase by over a percent, to 7.5%, which is getting close to this high level that traditionally African-American employment has been at—8%, higher—levels that would be considered a serious recession if that were to be the unemployment rate for the country as a whole. So it is fascinating to see that Black unemployment, within a year’s period, had gone from about 6.2% to 7.5%.

Center for Economic and Policy Research (8/26/24)

JJ: And I just want you to underscore that if that number for Black unemployment were the national number, we would consider the country in a recession.

DA: That’s right. A serious recession. That’s right.

JJ: And let’s break it out, because I think folks are thinking of it this way, at least a little bit: The layoffs of Black people, and Black women in particular, from the federal government, that seems to me to be a clear illustration, were it needed, of how this supposed anti-government, or small government, project, whatever you want to think about its intentions, it is anti–Black employment in its effects, right? So when we’re looking at Black unemployment/employment, we have to look at the efforts of this administration to unemploy Black people through their attacks on the federal government.

DA: Yeah, the attacks were so strong; it was a mixture, on top of each other, of slashing government employment, which is a great path for middle-class security, in that they are professional jobs that oftentimes have good living wages, benefits, some aspects of retirement, and is the type of economic stability needed for, particularly, first generation/second generation middle-class or middle-income households.

But at the same time, there was a ramp up on the verbal attacks on diversity, equity and inclusion programs, as well as executive orders that directly undermined and attacked historic, like, 1965 Lyndon Johnson’s Equal Employment Opportunity executive order– tearing apart aspects that had been created in the federal government to inhibit or lessen discrimination and make it a place where racial minorities in particular could have greater opportunities.

ACLU (7/2/24)

So you’re having an attack on the civil rights infrastructure that’s in the federal government, as we’re also slashing positions and jobs, and having probably one of the most serious declines in federal employment, in a year, that we’ve seen in quite a while.

And then I’ll just add, one other thing that was happening at the same time were these tariffs, and the tariffs were having effects on small businesses across the country, and threatening their ability to understand their costs. Everyone’s talked about that this economy over the last year has been one of very little hiring—of generally not mass firing, except for maybe federal government, where they did push out hundreds of thousands of employees—but the private sector, in this insecure economic environment, has been very hesitant to bring on more staff.

So all of this, I think, has contributed to this substantive increase in unemployment for African Americans.

JJ: Just even in what you’ve just said, I think folks might hear this is just bald economic data. These are choices. And where I fault media is the failure to translate what might seem like across-the-board economic decisions, and to spell out the way that that has a special impact on Black and brown and non-white communities, and to identify the way that there is not “one” economy. And so when you make tax policy decisions, when you make decisions about which businesses you’re going to support, those are things that have racial impacts. Even if you, as a listener, don’t understand, or don’t want to believe, that they have racial intentions, the fallout says what it says.

DA: Yeah. And, honestly, it’s harder and harder to think that there aren’t racial implications when, actually, the federal government is saying that we really can’t talk about African Americans, women, Latinos, and inclusion of them in hiring, but we should be focusing on anti-discrimination efforts for whites. And so, to act like the administration is saying we should not talk about racial discrimination, is not true. They just don’t want to talk about racial discrimination about anyone other than white people. And maybe sometimes I’ve heard things about Christians. And so it’s been even a harsher rhetoric and a harsher reality than we’re used to.

JJ: Absolutely. Well, when we spoke in 2024, you noted that, at the current rate, it would take over 500 years to bridge Black/white income inequality, and nearly 800 years to bridge Black/white wealth inequality. And I would encourage interested folks to look into that interview, where we talk about the difference between income and wealth.

But we live in a country where we were told we would move on non-white people enjoying basic rights “with all deliberate speed.” (That’s Brown v. Board of Ed.) And Black people chuckle at that, because we see the message, “all deliberate speed.” We see that message, which is, “We want you to stay invested in the idea that this will happen, but our actual goal is to slow-foot it, so that it never happens.”

And I fear that equity is seen as something that’s not achievable, it’s too vague and weird, or, it’s something that we tried and it failed, and that there’s not been an understanding that this is work, this is a project, and it’s never been a polite, on-paper, logical kind of argument, yeah?

Reuters (12/30/25)

DA: And also, sometimes I feel like the conversation has moved to the extreme, the idea that racial discrimination is a thing of the past, so we no longer need to discuss these things. And, again, if we didn’t have serious racial economic inequality, if we weren’t at a space where it would take another 400, 500 years to get income equality, 800 years or more to get wealth equality, then there wouldn’t be a need for government programs, and focused research and analysis, in dealing with this problem, because it wouldn’t be a problem. But it is a serious problem.

And one of the things that is also disheartening is the removal of government agencies to even have that type of analysis, to recognize that this is still a serious problem, and then to be able to track how, if you’re going to push out 270,000 federal employees, OK, well, is that having racial implications? Is it having gender implications? Does it have any geographic implications? How is change in the federal workforce actually occurring? Will it affect particular communities? Will it affect the type of policy and the ability for the government to administer and do the work that we are hoping the country does do?

JJ: And that’s the whole thing about what we’re hoping the country does do, because we’re always being asked to produce evidence, to produce data, to produce proof that there is such a thing as discrimination. But when you then say, well, all right, Black people don’t get leases here, we don’t get loans here, we don’t get hired or promoted—we’re still back at a place where it’s OK to just say, “Oh, well, you’re getting differential treatment because your actions are different.” It’s like it’s a respectable perspective to say, “Oh yeah, you can show us numbers—we just don’t care.” We can’t change the narrative with data, necessarily, because no numerical evidence seems like proving inequity will matter to some of these folks.

DA: And I think that there’s a reason why there is an attack on racial equity programs, or racial equity analysis, in government. They are doing that because they do feel that it changes the conversation, that if the Treasury does have a racial equity analysis of what’s going on in the economy, that it will show the need for better regulation, anti-discrimination, and for bridging inequality that they don’t want to deal with.

So I do think it is important to have these agencies do these types of analysis. And there’s some spaces where they’re just trying to roll them up all together, whether it’s the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, which, for a government agency, is still pretty new. We’re talking about issues of affordability, and I think the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau has actually been one of the government agencies most focused on dealing with the day-to-day, nuts-and-bolts financial issues that can make life so unaffordable, with different types of schemes and loans and predatory products that make middle-income life that much more challenging.

So it is a full-scale assault on particular programs in different agencies, and some trying to roll back agencies altogether, including the Department of Education. You mentioned Brown v. Board of Education; there’s a reason the Department of Education, historically, has been looked at as a civil rights agency of the United States, because it was trying to at least analyze what type of “deliberate speed” we were doing in breaking up segregation. And it’s no longer acceptable just to slow roll it; it’s “let’s roll up that whole department,” so there isn’t the pressure to deal with these issues that we’re still trying to deal with, in terms of school segregation.

JJ: I feel like listeners are going to understand that we’re talking about a whole lot of stuff that we could talk about for a long time. I just want to say, I appreciate very much the way that the new report talks about employment, talks about economic factors, but also talks about social media and AI and historical deletions from government websites, because people live 360 degree lives, you know? We’re not a compilation of factors, these things interweave; but if someone asks you, “Well, why are you talking about broadband? Why are you talking about school library policies, when you’re talking about the state of the dream?” How do you respond to that theoretical question?

Popular Information (1/13/26)

DA: Well, I mean, I think broadband’s an important point, and I’m just going to highlight, again, this is a 60-page report, and so obviously we’re not going to have time to talk about all aspects of it. And it’s done with many contributors, all throughout our organization, the Joint Center for Political and Economic Studies. We utilize other organizations, like the National Community Reinvestment Coalition and the Center for Economic and Policy Research. A lot of people came together for this, and we’re hoping that by having all of these different categories—entrepreneurship, financial deregulation, broadband policy—people can hone in on the issues that are most interesting to them.

But everybody’s talking about AI and technology. If you don’t have access to fast and affordable broadband, you are clearly going to be left behind, as we’re talking about artificial intelligence and robots and technology in the 21st century. So we still need some of these nuts-and-bolts policy areas that make everything else even exist, or provide pathways of access. So that’s why, still, too many Americans, rural Americans, economically insecure Americans, don’t have strong access to broadband. So it’s very challenging to tell them how to get ready for the artificial intelligence world, when they can’t even get on the internet.

JJ: And also (we’re going to go back to economics,) we’re going to try to tell them to figure out where they lie in terms of what they’re paying for prices? If you can’t stay in communication, there’s a loss there. And media seems to be a connecting thread, in terms of even these economic issues that we’re talking about.

DA: That’s right. Because more and more people turn to social media for all of their consumption, whether it’s entertainment, whether it’s news, whether it’s understanding even what’s happening at your local schools, people turn to social media channels for that. So it’s important you understand social media policy, and how these things are changing, and how so much of the change that happened in social media policy in 2025 was more from the platforms themselves, less so from outright government legislation, and what type of social media platform policy changes were occurring.

JJ: Well, I’m not mad about corporate news because it’s my job; it’s my job because I’m mad about it. And one of the things that I’m mad about is the way that they disaggregate and separate stories about Black people and immigrants and poverty and tax policy. They separate out these stories in a way that undermines our ability to connect dots, and to see, not just how communities are harmed in layered and intersectional ways, but also where there’s opportunity for connection and for shared purpose.

So I want to end where the report ends, which is a reminder of Dr. King’s question, “Where do we go from here? Chaos or community?” I don’t think I’m being over-hopeful to say that every day I see more people waking up to that question, accepting that that’s part of their lives, and being prepared to engage it, because they don’t want to give up. And so they’re asking themselves, chaos or community? Just any final thoughts from you.

Dedrick Asante-Muhammad: “People want to talk so much about the King holiday as a time for community service, but it’s really a time for community action.”

DA: Yeah, no, it’s fascinating, I think–this is an address and then a book that came out in 1967, Where Do We Go From Here: Chaos or Community–how much that captures today’s moment, where I feel like people are, you know, you turn on the news and you feel like it’s constant chaos. And there’s a feeling, too, of a real lack of community: lack of community with polarized politics, lack of community in that we’re not in touch in real life with people. We’re kind of doing everything through the internet.

And so I wanted to do this type of report, because Dr. King was very clear that his beautiful, idealistic language had to connect to the socioeconomic realities that people are living in.

And some people tried to diminish Dr. King’s birthday. I look at that, not just as history, but as a guide, how he was dealing with similar types of challenges during his time period, and how he was able to have hope for the future and actually push for policy change.

And so that’s why I think it’s essential, when people want to talk so much about the King holiday as a time for community service, but it’s really a time for community action, policy analysis and socioeconomic advancement. And we’re trying to bring that back to the memory of who Dr. King was, and what he did.

JJ: I’m going to end it there for now. We’ve been speaking with Dedrick Asante-Muhammad. He’s president of the Joint Center for Political and Economic Studies. You can find the report we’ve been talking about, and a lot more, on their site, JointCenter.org. Dedrick Asante-Muhammad, thank you so much for joining us this week on CounterSpin.

DA: Oh, and thanks for your continued analysis and reporting on these issues.

This content originally appeared on FAIR and was authored by Janine Jackson.