Image by Annie Spratt.

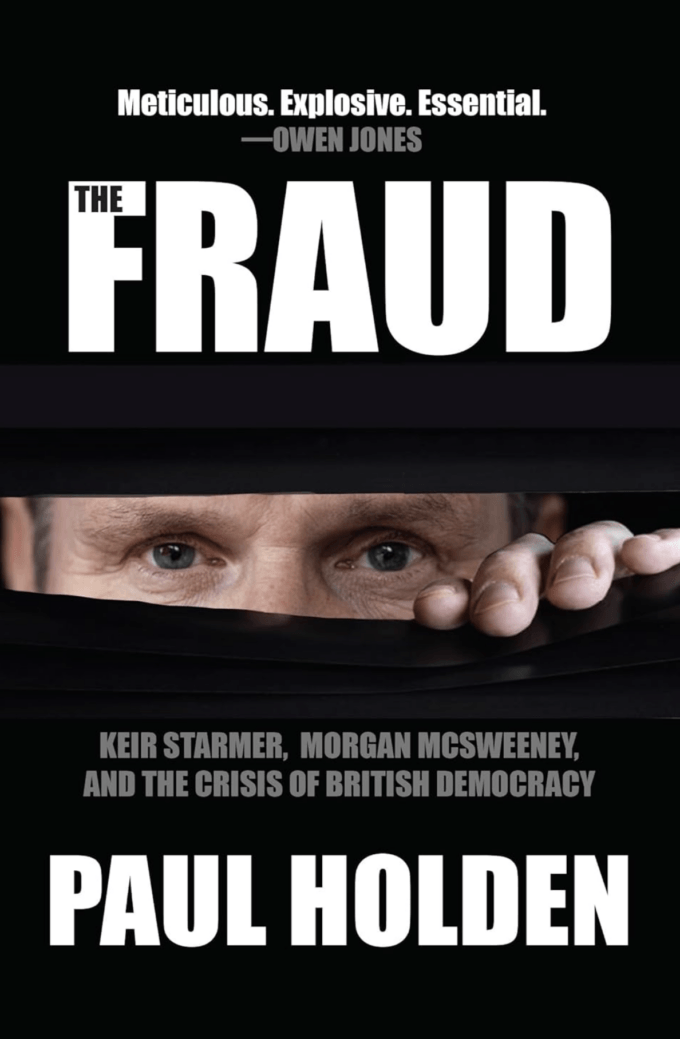

Paul Holden, The Fraud: Keir Starmer, Morgan McSweeney, and the Crisis of British Democracy. New York: OR Books, 2025. 534pp. $26

+++

More than a half century ago, Ralph Miliband’s Parliamentary Socialism—published by Monthly Review Press in 1964—described the uncertain course of the Labour Party. It was, truth to tell, pretty much always uncertain about what its leaders meant when they called themselves socialists.

They had carried over a vague sense, from earlier generations, that capitalism, a system of exploitation, somehow and sometime had to go. But left to their own devices, they could just as easily devote themselves protecting the Monarchy, a favorite project of Harold Wilson. Or to demanding somewhat better government services in lieu of public ownership of the means of production. At moments of real social crisis, as in the early 1930s, they would rush to join the Tories to save society, that is, to save capitalism from public bankruptcy. At present, they seem to be in a rush to do the same.

And here we are in 2026, amidst a Labour Party collapse from within. Most US readers, especially those who mainly take pleasure in visiting England, Scotland or Wales, may be missing the scale of the drama now taking place. Elected in historic parliamentary numbers by a historically low voter turnout in 2024, seemingly secure until at least 2029, the Labour Party is now at 15% public approval. “Reform,” the anti-immigrant party, seems to be filling the void, with a following twice that large. And yet demonstrations supporting the Palestinians are everywhere, especially in the Gaelic zones, i.e. those historically colonized by England. The Green Party is more openly socialistic and attracting new members. Further to the Left, a group calling itself Your Party is in the process of launching itself formally, struggling to sort out how to move ahead.

“Dysfunction” seems meanwhile to have become a favorite word to describe the flailing of Labour leadership. A desperate (perceived) need to please American leaders, ak Trump, has PM Keir Starmer desperate at once to hold Nigel Farage of the anti-immigrant party at bay and somehow to woo Farage’s US fans and partners, notably Vice-President Vance. Likewise to convince union leaders to stay in line while refusing to tax the super-wealthy, as a feeling of desperation spreads across the landscape. And insisting that his leadership, alone, can halt the largely imagined wave of anti-Semitism, especially present among critics of Israeli behavior in Gaza.

Looking back, the programmed expulsion of its Left, from Labour veterans of long (and high) standing to maximum cultural figures like film-maker Ken Loach, seemed, at least to the leaders around Keir Starmer, to be an effective consolidation of their power. Instead, it dramatized the top-down mentality of the leadership as one after another of the campaign promises around the welfare state are jettisoned in favor of rewards to corporations of various kinds, including prospective nuclear power plant hucksters.

Fraud allows us to take a step yet further back in time. The rise of Jeremy Corbyn to the leadership of Labour during the middle and late 2010s seems, in retrospect, to have been an astonishing feat. No one nearly so far to the Left, on global issues in particular, had captured Labour’s leadership. In more recent decades, the shame of Tony Blair—unindicted war criminal in the eyes of the public—made the rise of the Left possible. Corbyn was never the most brilliant orator or even best strategic advocate of that Left. Rather more of a moral leader in a moment of exposed immorality, he expressed aloud the public sentiment, as the British, notwithstanding their own centuries-long tradition of torture, winced collectively at the chambers of horror created for George W. Bush’s Iraqi campaign.

Whatever Corbyn’s weaknesses, his vote totals in 2017 against a winning Tory party stunned observers, devotees and opponents alike. He and his supporters, or more properly their vision of a different British society in a different world, had touched a new constituency, mainly young idealists along with minorities, especially the growing Muslim minority that had been ill-treated, regularly accused of disloyalty and worse whenever the Israel abuse of Palestinians came into public view. They turned out in massive numbers, as the old Labour constituencies continued to fall away with the closure of factories and the memories of “pit villages,” the cohesive and class conscious coal villages, sunk further into memory. And more specifically: as the ever-reliable, ever-crucial Labour vote from the North staggered into uncertainty.

Thus the conspiracy began, concocted in part by an erstwhile Blair insider, Morgan McSweeney. Paul Holden goes into detail, indeed so many details that it takes determination to take them all in, page after page. It’s a long book!

Starmer-centered projects under the umbrella “Labour Together,” aimed at anything but “together.” In hindsight, Starmer and McSweeney, mobilzing allies from 2015 onward, aimed at disestablishing Corbyn. An attempt to force him out in 2016 had already fallen flat, and the election totals of 2017 made the cries of the opposition worse situation worse precisely because Labour scored so big, in the face of bucreacratic efforts to direct party funds away from known Left candidates for office.

Starmer’s ardent allies, that is to say the bitter opponents of the Left, prominently included the reborn Jewish Labour Movement, known a century ago as the Poale Tsionists or Labor Zionists. Generations ago a working class Jewish movement with middle class participation, it re-emerged after decades of silence, now largely a movement of professionals and businessmen with scarcely a factory worker to be seen. The JLM was indeed a part of the Labour Party (as of old), but now prominently linked to a longer list that included the Board of Deputies of British Jews, the Zionist Federation and the World Zionist Movement, spiritually connected to the more or less defunct Labor Party in Israel.

The funding of the mendacious anti-Corbyn strategy, according to Holden, cannot be limited or properly attributed to the Jewish establishment. But it can be traced to hedge fund mangers and a handful of businessmen, coming together decisively at the moment of Corbyn’s surprisingly high 2017 vote. They would be swiftly joined by the right-leaning press, eager to find an alternative, another Labour leader making no unpleasant demands upon big business or the foreign office, also one strongly deferential toward US foreign policy. Brexit offered that opportunity.

So much time now seems to have passed, so many events including the Covid Moment and the return of Trump to the White House, that we have forgotten the Brexit Effect on British politics. Corbyn and Labour faced the horns of a dilemma with the inevitability of a second referendum on Brexit, after one passed by the Tory government in 2016. To oppose Brexit would threaten the working class base, wrongly taught to consider it their salvation, while to support it vigorously would be viewed as treachery to the educated middle classes. Weak support, the Labour default position, pleased no one.

Labour did indeed lose the Northern “Red Wall” in 2019. Holdon argues that this calamity must be understood together with something more subtle: the charge that Corbyn, and all around him, had become the supporters of the growing Muslim presence in the UK and by that measure but by support of the Palestinian cause, an anti-Semitic menace to liberal society. This anti-Corbyn strategy, if ridiculous on its face, purported that the strong Jewish element in the Labour Left, anti-Zionist and more strongly supportive of the beleaguered Palestinians, had become guilty until proved innocent. Those Jews most prominent on the Left, a disproportionately elderly crew with familiy and community memories of fascism, have been pilloried ever since.

Participants in Jewish Voice for Labour could expect expulsion and by Fall, 2025, “Palestinian Action” marchers holding up signs indicating support for Palestinian rights, were subject to arrest, supposedly for threatening national security by throwing red paint on weapons made and prepared to send to the IDF, that is, to be used on Gazans. The sight of elderly men and women dragged away offered an especiallly ugly face to Starmerism.

Only a half dozen years earlier, Starmer had carefully sworn his fealty to Corbyn, no doubt because the 2019 Labour defeat nevertheless left in its wake wide sympathy for the vanquished political champion of social change and human rights. Starmer’s “Ten Pledges” set forth to win back Labour voters largely echoed Corbyn. Starmer’s promotional videos included the determined British marchers against the invasion/war on Iraq that Tony Blair had made his own global crusade. Indeed, photos of Starrmer embracing Corbyn, a very few years before denouncing him as an agent of antiSemitism, remain vivid in rewatchings today.

“Labour Together,” the slogan of the enmerging new leadership, actually disguised a campaign of anything but unity. A very strong argument in Fraud recovers how, by 2023, Labour’s emerging leaders were lurching Rightward. They had come to assume, as per US Democratic leaders, that loyal voters would remain loyal while “the middle” was to won over on crime, immigration and reassurance of properly rights. Corbyn himself was effectively drummed out of the Party, along with a wide circle of respected local and union leaders. In this, at least, the new leadership proved highly effective.

Now, as the author says, the genius strategists have run into a wall of their own making. Supporting what amounts to Genocide in Gaza is not a crowd-pleaser. Reducing social benefits while offering tax breaks to the rich, revving up war fever in a crusade for the Ukraine—these do not go over big. Nor did the demonizing of racial minorities, resented in particular by Muslim communities that had, in recent decades, supplied Labour with the vote totals lost to vanished working class constituencies. The Green Party on the Left and Reform on the Right continue snapping up voters.

Two events of recent days drive home key points in this book.

First, the Mamdani campaign seems to have had a huge, perhaps unexpectedly huge, effect on the British political class. The very idea of building a frankly socialistic movement up from the grass roots is rewriting opinion polls, making Labour Party leaders nervous.

Second, the convention launch of the project known as “Your Party,” over the final weekend of November, 2025, appears to be the badly-awaited, uncertain but vastly hopeful sign of a new beginning for the British Left.

Whether that newer Left will be able to overcome all the obstacles ahead, from the financial and institutional backing of Labour’s bureaucracy to the painfully impressive momentum of Reform? We will surely see. But Paul Holden’s Fraud gives us a road map of sorts, and we are grateful.

The post The Crisis of British Democracy appeared first on CounterPunch.org.

This content originally appeared on CounterPunch.org and was authored by Paul Buhle – Raymond Tyler.