(As I was getting ready to send this to CounterPunch, I received word from Marc’s wife that he had passed in the night. I will write a tribute to him once I gather my thoughts. I’ll miss him as a friend, editor and co-conspirator.–Ron J., August 11, 2025)

“People are up to their ears in facts. What they want is story; what they need is story.” So explains the fictional author to his audience near the beginning of Marc Estrin’s 2008 novel The Annotated Nose. It might seem cliche to suggest here that it is in the story that the truth often lies. Yet the truth (there’s that word again) is that this is a fact more than many of us will, upon reflection, acknowledge. While he might publicly reject the notion, Estrin has revealed many truths in his novels and tales. He does this through the magic of fiction and his often magical use of words and the concepts words describe. Informing it all is an underlying theme that contemplates the so-called Other while exploring the Other’s role in revealing certain truths, both through the Other’s existence and its interaction with the majority.

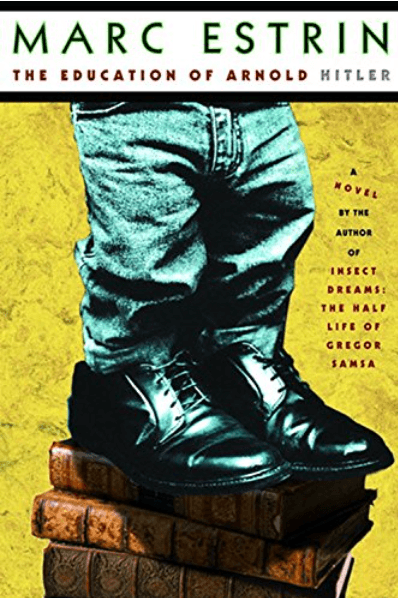

The task Estrin has given himself is one that requires a keen sense of life’s contradictions; of history’s role in creating the future, often in ways few if any could have foreseen. It’s also a task where a sense of humor facilitates the story while assisting in revealing the consequent truth. Perhaps no novel of Estrin’s does this more obviously and with a recognizable delight than his tale of a blonde boy from Texas with the name Arnold Hitler. Titled The Education of Arnold Hitler, Estrin’s novel begins in the small southern town of Mansfield, Texas; the town where John Howard Griffin, the author of the 1961 book Black Like Me, was born. For those unfamiliar with the book, it describes the experiences of the author—a white man—who has his skin darkened and passes as a Black man in a journey across the Deep South in the US. It’s not something anyone would get a book contract to write today, but it was quite a sensation in the early days of the 1960s when legal apartheid described the US South.

Arnold, being blonde, is Estrin’s archetypal Aryan. Of course, Arnold doesn’t have a clue about Aryanism, white supremacy or Dachau. After all, he’s just a white kid in white America doing white kid things. He means no harm. It’s only when he goes east to college on a scholarship that he genuinely realizes that his name can be a problem. Not the Arnold part of it, mind you. Jewish students ostracize him and student Nazi clubs try to recruit him. Arnold just wants to be a college student who’s interested in college things, which in the late 1960s means protests and marijuana, among other things. He could change his name, but that wouldn’t address his intellectual crisis; it would only ignore it. The weight of history is carried in his name and on his shoulders as much as the weight of history is carried in the guilt of the German nation after its murderous Nazi orgy of violence and rationality. His soul-searching includes a conversation with MIT professor Noam Chomsky, a friendship with Leonard Bernstein’s daughter, a kiss from the maestro, intimidation from Harvard white supremacists and a couple of women.

Estrin’s work includes seventeen novels, a couple essay collections and two books he considers memoirs. Of the latter, one is a discussion of the art of writing and the other—titled Rehearsing With Gods: Photographs and Essays on the Bread & Puppet Theater—is a beautifully constructed reminiscence/history of the Bread and Puppet Theater, a phenomenon unique in the world. Estrin was one of the early recruits to the puppet theater group; he joined a few years after Peter and Elke Schumann introduced Bread and Puppet to the world in 1963. At the time, Estrin was working in Washington, DC’s Institute for Policy Studies and had founded (with James Livingston) the antiwar guerrilla theater troupe known as the American Playground Theater which was merely one element of the new left counterculture Washington Free Community in the late 1960s. The Free Community included Raymond Mungo and Allan Bloom’s underground media clearinghouse Liberation News Service, draft resistance organizations and numerous other artistic and political endeavors challenging the imperial war machine at its center. Prior to his residence in DC, Estrin had been part of San Francisco’s Actor’s Workshop, directing Michael McClure’s play The Beard. After turning down McClure’s request to take the show on the road, he spent time in Pittsburgh’s alternative drama scene. One of my favorite stories of Estrin’s involves his meeting with rock music impresario Bill Graham in the then cobweb-covered, rat-infested building in San Francisco’s Fillmore District that would become synonymous with the San Francisco rock scene and Graham himself—the Fillmore West. Estrin determined the building was not what he was looking for in terms of presenting plays and Graham left his job as manager of the San Francisco to become the world’s best (in my opinion) promoter of modern popular music.

I was part of a small collective of people publishing a local agitational newspaper called the Old North End Rag in Burlington, Vermont, in the late 1990s and early 2000s when Marc began sharing the draft of a novel he was writing. Although it was the second novel he had written, it would be the first to be published. And it would be published twice—once as the 2002 Putnam/Blue Hen title Insect Dreams: The Half-Life of Gregor Samsa and later as the 2017 release Kafka’s Roach (Fomite). The latter version is essentially what is called the director’s cut in cinema. In other words, it’s the manuscript I was reading as Estrin finished each chapter back in 2000-2001. It’s the same tale as Insect Dreams only with many details filled in and no wormholes across time..

The story begins the day Franz Kafka’s human wakes up as a cockroach but with a different outcome than the one determined by Kafka. Instead of dying alone and unwanted, he remains Gregor Samsa and goes on to live a life most humans can only imagine. Gregor reads Spengler to audiences in a sideshow act as the Nazis take over Germany; he flies across the Atlantic and ends up having a dance named after him. He then goes to work for Charles Ives as a risk management genius in Ives’ insurance business. There’s romance and an eventual job in the FDR White House. It’s a job that takes him to Los Alamos, New Mexico and the Manhattan Project’s development of a nuclear weapon. Samsa’s final act is to immolate himself in the first test of the discovery that changes the world, in the explosion that saw humanity become the destroyer of worlds. It’s a human moment where the pursuit of science alone requires a barrage of inquiry; maybe the ultimate such moment. Is it worth planetary suicide to answer the question of nuclear fission? Is it worth planetary suicide to build a better a better bomb, especially when that bomb’s purpose is the incineration of human lives?

It should be apparent from the quick plot description above that Estrin is not just interested in telling a good story. Indeed, Insect Dreams/Kafka’s Roach also serves as a history of the twentieth century up to the time of Samsa’s death. That in itself is quite a story; a story that is certainly full of sound and fury even if we have no idea what, if anything, it signifies. Estrin’s life work is one that simultaneously seeks some significant understanding that there may be none while also doing his part to give this life, these lives, this human species some meaning. I wrote this in a 2017 review of Kafka’s Roach: “The underlying context of Marc Estrin’s novel Kafka’s Roach: The Life and Times of Gregor Samsa is the relationship of the Other to a world where its inhabitants reject, ignore and even murder those it considers different. To emphasize this, Estrin’s Samsa is both a cockroach and Jewish; both of them the subject of revulsion in many circles.”[1] Alienation as a way of life, in other words.

If there is one theme that runs through Estrin’s major novels, it would be the one described in that quote. That’s clear in his second published novel, which I refer to in my earlier paragraphs, and it is also apparent in his 2008 novel The Annotated Nose, a sort of metafiction of a fictional novel titled The Nose that exists only in the universe Estrin creates in his novel appropriately titled The Annotated Nose. This is at first glance a merely playful book, but with each subsequent glance (if you will) it becomes a commentary on modern disconnections and the desire to transcend them, on the nature of popular culture and the role the market plays in such culture and, one could argue, the absurdity of it all. Told with Estrin’s particular humor, the reader is introduced to a cult-like sensation centered on a novel by a fictional author named Hundertwasser. This introduction is not through Hundertwasser’s text, however, but through the annotated text and commentary of Estrin’s fictional author Alexei Pigov, described in the book as a “premature goth.” It’s Pigov’s descent into a certain madness that informs The Annotated Nose and, together with the shadowy illustrations by real-life artist Delia Robinson (who also exists as a character in Pigov’s work), Estrin’s novel becomes an artistic delve into the truths of the human endeavor and the rationales for its often nonsensical and tragic reality.

Estrin has several other novels—one might call them minor works, although I prefer the term slight to describe them. Not slight in terms of themes approached or in questions asked, but merely in terms of size. Like the three fictional works mentioned (discussed?) here, all of Estrin’s fictions take place in a world where the fantastic never becomes commonplace. However the commonplace does become fantastic. For Estrin, life is not a joke, it has meaning, yet it is endlessly humorous. Although he might disagree, his fiction implies that it is because of that humor we humans have survived up to now, despite those whose science, politics and economics conspire to destroy us.

In 2011, Marc and his wife Donna Bister told me they were considering starting a small literary press. Estrin’s experiences with the world of corporate publishing had convinced them both that too many good if not excellent writers were not getting published because of the corporate bottom line, despite the numerous imprints that existed as subsidiaries of the corporate houses at the time. I encouraged the idea. Soon thereafter, they asked if I had a manuscript that might be ready. I did. My novel The Co-Conspirator’s Tale became the first book published by the infant Fomite Press. Since that first book, Fomite Press has published over two hundred books. Their list includes novels, short fiction, poetry, creative non-fiction, essays and a number of unique books combining text and graphics from Bread & Puppet’s Peter Schumann. Since October 7, 2023 much of the press’s focus has been on publishing books about Palestine and against the ongoing genocide there. I mention Fomite primarily because it is an embodiment of Estrin’s ongoing project that invites and encourages the mysteries of circumstance, the pursuit of truth and the repercussions and ripples of both the pursuit and the truth itself.

In 2009, Estrin’s novel The Good Dr. Guillotin was published by Unbridled Books. Nominally the story of the invention of the tool for execution bearing the good Doctor’s name, it is also a musing on revolution, the common man(woman), science (again), and killing by the State. Around the time of the novel’s release, I conducted an interview for Counterpunch magazine with Estrin. The 2008 election (Obama’s first term) was still relatively fresh in the popular mind. Here is a brief excerpt:

Ron Jacobs: Ah, yes… the Faustian bargain. I think we’ve all made a few–at least at a personal level–to get a job or maintain a relationship. However, the ones I’m more interested in are those that we make in the political/economic realm as a people. Last November’s election appears to me as a Faustian bargain of this type. Hell, every election is a Faustian bargain of a sort. Anyhow, back to the more general one we make as residents of the United States — we know what our government, its military and the corporate/financial monoliths do to maintain our standard of living… and we support it, if only tacitly. Keeping Nicholas Pelletier (Pelletier is the name of the first person killed by the guillotine)in mind, one could argue that it is only the criminals and others — those that Bob Dylan called “the luckless, the abandoned an’ forsaked”–that do not make this bargain. But then, they probably make their own with Mephistopheles in another form. I guess my question is–can any human in our modern society avoid the Faustian deal?

Marc Estrin: Faustian bargain:

Let’s make some distinctions because not every bargain is a Faustian bargain. The key dynamic in the Faustian bargain is a quest – for knowledge, or power, or the establishment of some ideal – with every attainment receiving some unexpected blowback, usually a just punishment.

I don’t think the US elections represent a Faustian bargain: we certainly don’t learn anything from them, nor do we get any power, nor do we further any ideal. Rather the opposite in each case. [2]

I quote this section of the interview if only to illustrate a foundation of the world Estrin creates in his fiction; a world where despite a daily reality that may be a constant set of negotiations that often mean little, there are humans who still pursue a quest beyond the daily negotiating session.

In the world of Estrin’s fiction, the person pursuing that quest might very well be a human sized insect.

1. Jacobs, Ron, “Gregor Samsa’s Twentieth Century Blues: Marc Estrin’s Roach Novel”,CounterPunch, September 5, 2017, https://www.counterpunch.org/2017/09/05/gregor-samsas-twentieth-century-blues/ ↑

2. Estrin, Marc & Jacobs, Ron, “Dr. Guillotin and Dr. Faustus,” Dissident Voice, September 19, 2009, https://dissidentvoice.org/2009/09/dr-guillotin-and-dr-faustus/

The post Marc Estrin’s Fictions of Alienation appeared first on CounterPunch.org.

This content originally appeared on CounterPunch.org and was authored by Ron Jacobs.