This content originally appeared on Open Culture and was authored by Colin Marshall

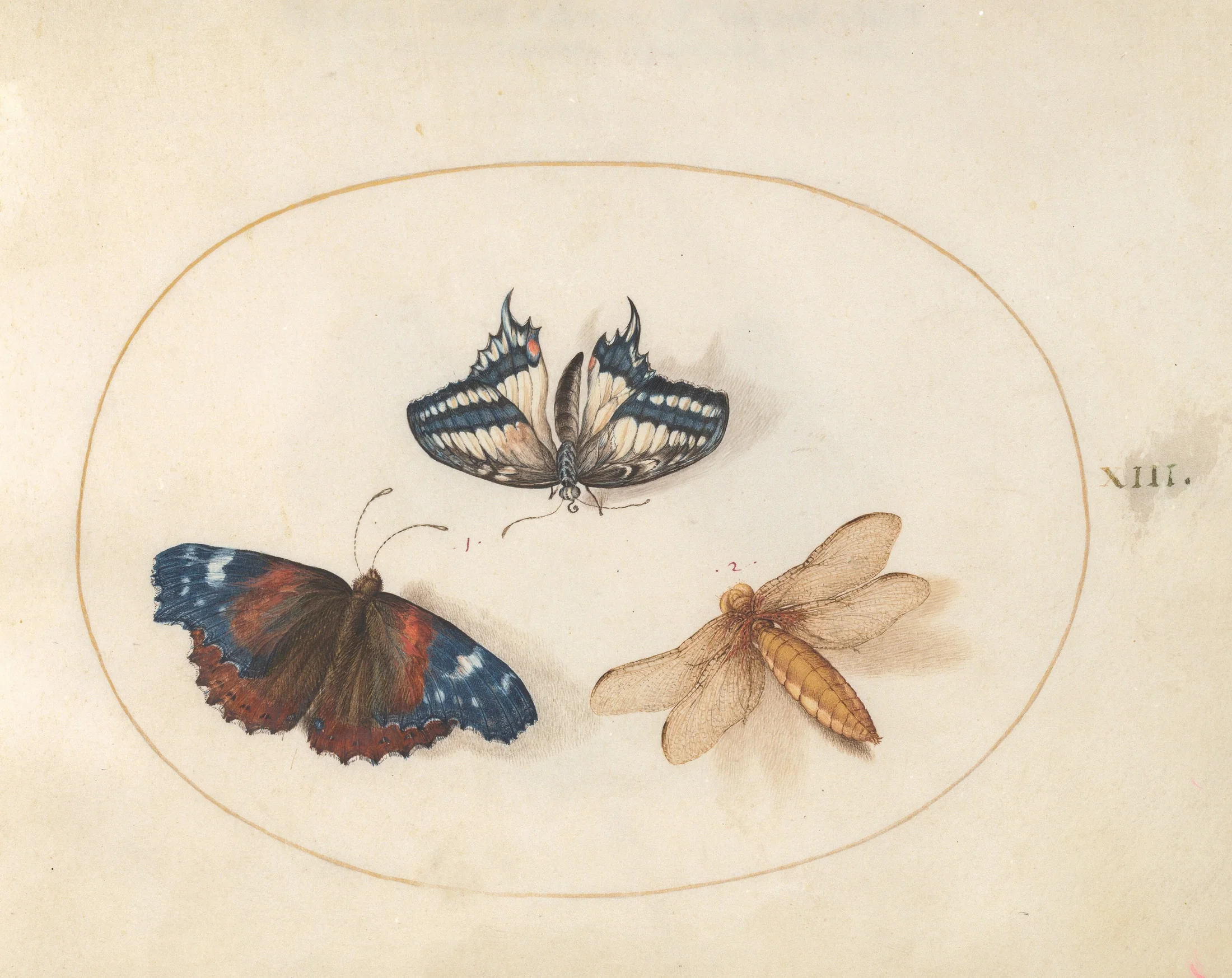

In English, most of the words we’d use to refer to insects sound off-putting at best and fearsome at worst, at least to those without an entomological bent. Dutch, close a linguistic relation though it may be, offers a more endearing alternative in beestjes, which refers to all these “little beasts” in which the artists and scientists of Europe started to take a major interest in the late sixteenth century. As was the style of that era, the magisteria of art and science tended to overlap, a phenomenon nowhere more clearly reflected — at least with regard to the insect kingdom — than in the work of Joris Hoefnagel, a Flemish artist whose illustrations of beestjes combined beauty and accuracy in a manner never seen before.

You can now see Hoefnagel’s art up close at the exhibition Little Beasts: Art, Wonder, and the Natural World, which will be up at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC until early November. If you won’t be able to make it out to the museum, have a look at the exhibition’s web site, which shows off the splendor of Hoefnagel’s work as published in The Four Elements, a collection of about 300 watercolors grouped into four volumes in the fifteen-seventies and eighties, each one named for an element: Aqua contains water animals; Terra land animals; Aier birds and plants; and Ignis, or “fire,” insects.

“We don’t really know why Hoefnagel put insects in the fire volume,” says Evan “Nerdwriter” Puschak in the new video above. “Maybe because both fire and insects symbolize transformation.”

“What we do know,” Puschak adds, “is that these insect miniatures are magnificently rendered.” Hoefnagel even made improvements on the nature illustrations of his artistic predecessor Albrecht Dürer, whose own abilities to render our world with fidelity had been regarded as nearly superhuman. One particular work that surpasses Dürer is Hoefnagel’s depiction of a stag beetle, which he accompanied with the Latin inscription “SCARABEI UMBRA,” or “the shadow of the stag beetle”: possibly a reference to the unprecedented realism of the insect’s shadow as Hoefnagel rendered it, but in any case a common saying at the time about hollow threats. For however frightening the stag beetle looked, as Hoefnagel well knew, the actual creature was gentle — just another wee beastie after all.

Related Content:

The Genius of Albrecht Dürer Revealed in Four Self-Portraits

Vladimir Nabokov’s Delightful Butterfly Drawings

Two Million Wondrous Nature Illustrations Put Online by The Biodiversity Heritage Library

Captivating Collaboration: Artist Hubert Duprat Uses Insects to Create Golden Sculptures

Watch The Insects’ Christmas from 1913: A Stop Motion Film Starring a Cast of Dead Bugs

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities and the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles. Follow him on the social network formerly known as Twitter at @colinmarshall.

This content originally appeared on Open Culture and was authored by Colin Marshall