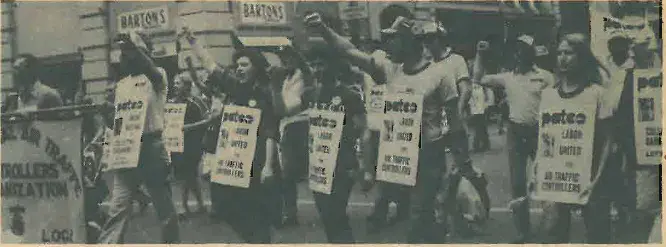

Patco Strike protests. Photo: Socialist Worker archives.

I had recently turned twenty-one in 1981, when President Ronald Reagan fired thirteen thousand striking air traffic controllers. It was a hot muggy August day in Boston. I remember that myself and one of my oldest friends Bill Almy were driving past the Boston Common, the country’s oldest public park and refuge for the city’s residents in the downtown area, when it was announced on the radio. Bill’s car has no air conditioning which added to the already stifling atmosphere of Reagan’s first term in office. We both looked at each other and wondered what would come next.

The Reagan administration’s destruction of PATCO was an historic turning point, not simply for the organized trade union movement at the time, but for the fortunes of the entire U.S. working class during the four decades that followed. “Concessions” became the watchword of contract negotiations. The ongoing deregulation in the airlines, banking, and trucking industries meant that such unions as the UAW, the Steelworkers, and the Teamstersshrank to the margins or literally disappeared from key sectors of the U.S. economy, while new, non-union employers emerged. In many ways, we have never recovered from the destruction of PATCO four decades later.

Today, Donald Trump and his chief hatchet man and Nazi sympathizer Elon Musk are carrying a much greater and deeper attack on basic constitutional rights, legal rights of workers, and the already thread bare welfare state that exists in the United States, something Reagan could not have imagined. Some call, “PATCO on steroids.” Faced with an existential crisis during the PATCO strike, the AFL-CIO, the United States’ main trade union federation led by Lane Kirkland, fumbled the ball. They protested loudly, organized a massive demonstration in Washington, D.C., and then told people to vote in the upcoming 1982 election.

If anything the AFL-CIO’s tepid response emboldened our enemies. Will the organized trade unions’ response to the Trump-Musk offensive fare better today?

PATCO

A few months before PATCO went on strike, newly sworn-in President Ronald Reagan had survived an assassination attempt. He was leaving a luncheon meeting with leaders of the AFL-CIO, the country’s largest trade union federation. Ironically, the man who killed the trade union movement was saved by a trade union official. He was much closer to death than revealed at the time, but Reagan recovered and began to project the jovial virility that appealed to many conservative voters and working class, male Democrats. The clever White House propaganda about his recovery boosted his popularity.

While Reagan won a landslide victory over the hapless, Democratic incumbent Jimmy Carter, he was viewed as a throwback to the McCarthy era. Reagan’s militant anti-Communism and dangerous swagger many feared would lead to nuclear war with the U.S.S.R. But, the assassination attempt wiped all that away, at least for a while. Veteran Washington Post reporter, the late David Broder wrote at time:

“The honeymoon has ended and a new legend has been born. … As long as people remember the hospitalized president joshing his doctors and nurses — and they will remember — no critic will be able to portray Reagan as a cruel or callous or heartless man.”

So, when air traffic controllers hit the picket lines on August 3rd, 1981 across the country, the political advantage was with Reagan. The whole story is best told in Joseph A. McCartin’s Collision Course: Ronald Reagan, the Air Traffic Controllers, and the Strike that Changed America.

Speaking from the Rose Garden of the White House, Reagan struck a moderate, almost reasonable tone compared to the current President Donald Trump. He leaned on his own history as a union president (he was president of the Screen Actors Guild (SAG) and a lifetime member of an AFL-CIO union), he defended the right the right of private sector workers to strike, and praised supervisors and workers who crossed the picket line in the name of public safety. But drew the line at public sector workers. Reagan declared, “If they don’t report for work in forty-eight hours, they have forfeited their jobs and will be terminated.”

Like many people who’ve written about the labor movement during the past four decades, PATCO, the acronym for the Professional Air Traffic Controllers Organization, was at the heart of any analysis of the collapse of U.S. trade unions for the two decades that followed. The facts are well-known. Little has changed with understanding what transpired and why since then. Nearly two decades ago, I wrote:

“You can rest assured that if I am elected president, I will take whatever steps are necessary to provide our air traffic controllers with the most modern equipment available and to adjust staff levels and work days so that they are commensurate with achieving a maximum degree of public safety, the Republican candidate for president, Ronald Regan promised Robert Poli, the head of PATCO in a letter dated October 1980.

PATCO, along with a handful of other unions including the Teamsters led by Mafia patsy and FBI informer Jackie Presser, endorsed Reagan in the 1980 presidential election, while the bulk of unions in the AFL-CIO endorsed the incumbent Democratic president Jimmy Carter, whose administration had broken every promise it had made to the labor movement in his four turbulent and disappointing years in Office.”

Jimmy Carter was widely despised in the labor movement. William Winpisinger, the head of the International Association of Machinists (IAM) and the only avowed “socialist” on the AFL-CIO, during an interview with the the New York City-based Village Voice, he was asked what could Carter do to redeem himself in Labor’s eyes? He responded, “Die.” In fact, Reagan’s blueprint for breaking the PATCO strike was drawn up by the Carter administration. The New York Times reported on August 6, 1981:

It was more than 20 months ago that the Federal Government began planning its response to a nationwide strike by air traffic controllers. Officials at the Federal Aviation Administration said today that they started in January 1980 to draft a detailed contingency plan for operating airport control towers and radar scopes with supervisory personnel, on the assumption that members of the controllers’ union might strike.

Reagan Administration officials enthusiastically polished and put into effect the plans first drafted in the Carter Administration. In the Federal Register of Nov. 13, 1980, the aviation agency published a ‘’national air traffic control contingency plan for potential strikes and other job actions by air traffic controllers.’’

PATCO’s picket lines were large and confident during the first days of the strike, but the atmosphere changed rapidly. I was a young member of the International Socialist Organization (ISO) and a student at UMass-Boston at the time. I have a hazy memory of going out to the PATCO picket line at Boston’s Logan Airport. A history of PATCO’s Boston Local 215 is available here. Kevin Murphy and Peter Lowber of Boston interviewed Local 215 Bill Robertson for Socialist Worker. Over one thousand trade unionist rallied in support of PATCO, which included teachers, postal workers, and Mike Ferman, PATCO’s eastern regional vice-president, who told the crowd:

“To hell with the laws against the air traffic controllers striking. If there’s an unjust law, if there is a fascist law, we’re right to break it. We’re right to fight it.”

My political education in labor struggles and socialist politics was in its early stages. Watching history unfold before me was thrilling but the confident atmosphere in the early days of strike turned darker after Reagan began to make good on his threats. The ISO’s monthly newspaper Socialist Worker had a tiny circulation but it’s first editorial “Union Buster Reagan”, though slightly behind political developments, captured what was at stake:

“They [PATCO] deserve to win — and they deserve the unqualified support of all airline workers — pilots, attendants, and ground and maintenance workers — and all workers. They can also teach Ronal Reagan a lesson. The president and his administration will take as much away from workers as they possibly can — with cuts and in contracts. The time to stand up and fight is now.”

A fractured labor movement

PATCO and its members were not simply badly prepared for the upcoming battle with the Reagan administration, it was so naïve as to be living in a delusional world. After Reagan fired PATCO strikers, the union’s president Robert Poli told the New York Times, “I have to say it was a surprise. ‘’I believe the air traffic controllers of the country, and myself included, never thought that would happen.’’ Why? Socialist Worker wrote at the time:

Ronald Reagan, of course, campaigned for president by boasting that he was a friend of labor and that he had himself once been a union officer. Some workers, apparently believed him. But if there were any doubts at the time, there should be none now. He is anti-union, and intends to give his backing to the union-busting campaign now in full swing in this country.

Reagan was successful with the postal workers. His threats — also of military intervention, firings, fines — worked against “militant” [postal] union presidents Vincent Sombrotto and Moe Biller.

Will they work against Robert Poli, the head of the air traffic controllers’ union and the 15,000 union members? Perhaps.

It became very clear that Reagan was not interested in bludgeoning PATCO into concessions but its destruction. Poli and the rest of the PATO leadership had not simply miscalculated what Reagan was up to but their own power. The New York Times reported in late October 1981:

The union believed that a walkout would dramatically curtail air travel and that the airlines and business executives, whose private flights would also be reduced, would bring pressure on President Reagan to accede to the union’s demands.

An article in a Seattle controllers’ newsletter before the strike said: ‘’Our power stems from one, and only one, source. That is our ability to withold our services en masse, thereby halting the air transportation system of this country.’’

Although air travel has been curtailed and passengers have been subjected to vexing delays, enough has been continued — about 80 percent, the Government says — to allow the system to function.

There was widespread sympathy for the air traffic controller among union workers in the airline industry, and in some eagerness to do something to support them. However, real solidarity — not verbal protests or wind-bagging at rallies — was not forthcoming. The most important union here was the Machinists led by William Winpisinger. PATCO appealed for support. The editors of the revolutionary socialist Against the Current (ATC) magazine wrote:

What was Winpisinger’s response to the PATCO workers’ request for support? He declared himself in full support and sent a letter to every airport IAM local, calling on them to give the fullest support to PATCO, with the small proviso that under no conditions should they take job actions.

This was followed by Winpisinger’s public pronouncement that every IAM local was free to “act according to their consciences” on the PATCO strike. This could of course be interpreted in two ways — as encouragement to act, or as a form of legitimation for those who did not want to do anything.

The test came when the San Jose, California, IAM, under pressure from its ranks, actually demanded that the International give them support in attempting to shut down the local airports. Winpisinger’s response was a prudent silence.

Without the IAM striking in support of PATCO with the full support of the AFL-CIO, the strike was doomed.

For those familiar with the history and politics of the U.S. labor movement this inaction was not a surprise. William Serrin, the chief labor reporter for the New York Times wrote at the time:

The strike also demonstrate[d] the fractiousness of the union movement. The movement has always been less idealistic and united than its statements and songs suggest, Jerry Wurf, president of the American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees, said in August.

Moderate unions, often with nothing to lose, oppose nuclear power; construction unions support it. Liberal unions often oppose military production; more conservative unions favor it, for it means jobs. Public sector unions, out of self-interest, support tax increases and oppose tax reduction referendums; private sector unions campaign for reduced taxes and are often vexed by the rising wages of public workers.

But a singular lack of solidarity marked this strike.

Solidarity Day

The lack of Solidarity on the picket line for PATCO appeared to be made up for by the AFL-CIO’s massive Solidarity Day march on September 19, 1981. For many people, the march was a direct response to Reagan’s strike breaking, but plans for the march were conceived much earlier. AFL-CIO leaders, especially federation leader Lane Kirkland, were frustrated and annoyed at being shunted aside by Ronald Reagan, who attempted to appeal directly to the ranks of the labor movement, with some success.

Reagan’s destruction of PATCO gave added urgency to Solidarity Day on top of his draconian cuts to social welfare spending and regressive tax cuts for the Uber wealthy. Historian Timothy J. Minchin Labor Under Fire gives us a vivid description of the vast outpouring of opposition to Reagan’s policies that the march expressed:

“Although it was initiated by the AFL-CIO, the march mobilized a broad swath of the American population. Its leaders — including civil right icons such as Jesse Jackson, Bayard Rustin, and Coretta Scott King — were diverse. Closely monitoring events, the Reagan administration estimated that no fewer than 250 organizations were taking part, including 100 unions, and a variety of civil rights, religious, and civic groups. Turnout was impressive. According to the National Park Service, 260,000 people attended Solidarity Day, more than the number that turned out for the iconic March on Washington in 1963 or the Vietnam Moratorium in 1969.”

Many participants and observers put the number at somewhere between 400,000 to 500,000 demonstrators, including six thousand PATCO strikers. It was no doubt a personal triumph for Lane Kirkland. Minchin’s book Labor Under Fire reveals many things about the organizing of the march that will surprise many people today, including, “Kirkland also permitted communist and socialist participation in the march.” It’s worth noting that the Teamsters were absent from Solidarity Day. If you look at the Teamster magazines for August, September or October 1981, you would never know that there was a PATCO strike, Reagan broke the union, or there was a massive labor march in Washington, D.C. in full view of Teamster headquarters.

I remember Solidarity Day quite vividly. It was a beautiful day. For national demonstrations, it was typical to drive down Washington from Boston late on Friday night and gather blurry-eyed with comrades and friends of the ISO, who made their way to the capital. There was a big push to get the tiny membership of the ISO out to the march. As the old ISO internal bulletin put it: “Most important — everyone should be there. It’s quite difficult, to be blunt, to imagine a socialist who would not want to be on this demonstration.”

Traveling around D.C. was made a lot easier because the public transit system was free that day, because the AFL-CIO covered the cost. The ISO gathered in this sea of people and were encouraged to march close but behind the Machinists contingent. While Kirkland allowed the left to participate in the march and Winpisinger’s reputation on being on the left, this didn’t work its way down to the ranks of the IAM, many of whom worked in the defense industry. Anti-communism was a very real thing. I remember there being a lot of tension, at least initially, with revolutionary socialists mingling so closely but it eventually dissipated.

Two of my most important memories of the march was that union contingents were well organized including banners, signs, and jackets, but many were uncomfortable with chanting slogans. The other memory was following the demonstration the ISO had a public meeting to assess the day. I remember the late Milt Fisk speaking and saying something like, “Some day I hope we can see workers in these great numbers, not just walking away after a great demonstration of strength, but to actually seizing power.” It was the first time I heard someone describe what a workers’ revolution would look like in the United States.

But, how to assess what Solidarity Day really meant? Minchin pointed to a serious problem with Solidarity Day from the very beginning. He wrote, “In protesting against the Reagan administration’s cuts, the AFL-CIO was on the back foot. A key problem was that the rally was held after the administration enacted its budget and tax programs, robbing it of the ability to block these polices.” True, however, the problems ran even deeper.

Socialist Worker’s editorial “Solidarity Day: It must be turned into action” declared that, “Solidarity Day was a fantastic success.”

“But there were important problems as well. First and foremost, the march was not used to organize and build support for the 12,000 PATCO strikers, despite the fact that some 6,000 air traffic controllers took part in the march and were greeted enthusiastically by nearly everyone they met.

The PATCO strikers are still fired. Their union is being destroyed. And daily the picket lines are crossed by all the other airport and airline unions. Secondly, it is clear, despite the absence of politicians on the podium, that the prime purpose of the demonstration was to give the Democrats a boost in their efforts to recover from Reagan’s victories in November [1982] and in Congress. A machinists banner read “Get Ready for Teddy.”

There were thousands of American flags on the march, even some confederate flags. At one point a huge part of the rally rose to sing “God Bless America.” The United Auto Workers union passed out tens of thousands of hats with the slogan “Buy American.”

Finally, the editorial continued:

The march can “only be the beginning” — if it means that more people take from it the lesson that words are not enough, especially in the case of PATCO. Action is absolutely necessary. And the lesson that rank and file organization is necessary, if the movement is to be built and carried on. And that the politics of the movement, including a socialist current, must be built.

Reading all of this four decades later, while I’m aware that there are many differences today, I’m also struck by how broadly similar and the political tasks for us remain the same.

The post “PATCO on Steroids”: Will Labor’s Response be Different Today? appeared first on CounterPunch.org.

This content originally appeared on CounterPunch.org and was authored by Joe Allen.