Part of a multimedia series on four RFA staff members who look back on life under the Khmer Rouge fifty years later

People streamed onto the streets as the Khmer Rouge soldiers entered Phnom Penh. For months, a relentless bombing campaign had the capital on edge. The war was closing in.

As soldiers clad in black uniforms marched into the city, thousands came out to cheer them on.

Soldiers of Cambodia’s pro-American Lon Nol regime waved white flags and laid down their guns. Civil servants watched on from their offices and shop owners and market traders cautiously opened their doors.

That was how the day began. By the afternoon, Phnom Penh, a city of 2 million people, was being forced at gunpoint to leave.

It was step one in implementing the vision of Pol Pot, the country’s new leader, of transforming the country into an agrarian utopia.

Sum Sok Ry remembers that morning. Dressed in short pants and a short-sleeved shirt, he stood in front of the doorway to his family home, waving as the soldiers went by.

There was a sense that the country’s civil war, which had raged for more than eight years and in which the United States had sided against the Khmer Rouge with a massive bombing campaign, was finally over.

“I remember it was one of the hottest days of the year, and it was Khmer New Year,” Sok Ry said.

Just hours later, they were ordered out of the city.

“It was so hot, burning. And the walk – I was crying so much because we were so confused.”

“They lied to the people that the Americans were going to bomb all of the city, all of the capital,” he said.

Between 1975 and 1979, between 1.5 million and 2 million Cambodians died by execution, forced labor and famine.

“I struggled so hard,” Sok Ry said. “I almost died so many times, but I refused to die.”

Ten years in a refugee camp

Sok Ry tells of the day his mother begged him to let her sneak into the cornfield he had been ordered to protect to pick food to eat. He first told her no, fearing that she would be caught.

“I was not the only guard,” he said. “There were many other boys, all sitting in trees looking down on the field. I was so scared.”

He told her she had to crawl into the field on her belly and “when you see the corn, just pick it and eat it, with your body lying flat.”

The first member of his family to die was his nephew, who was also just a young boy. His father was next, and then later his mother.

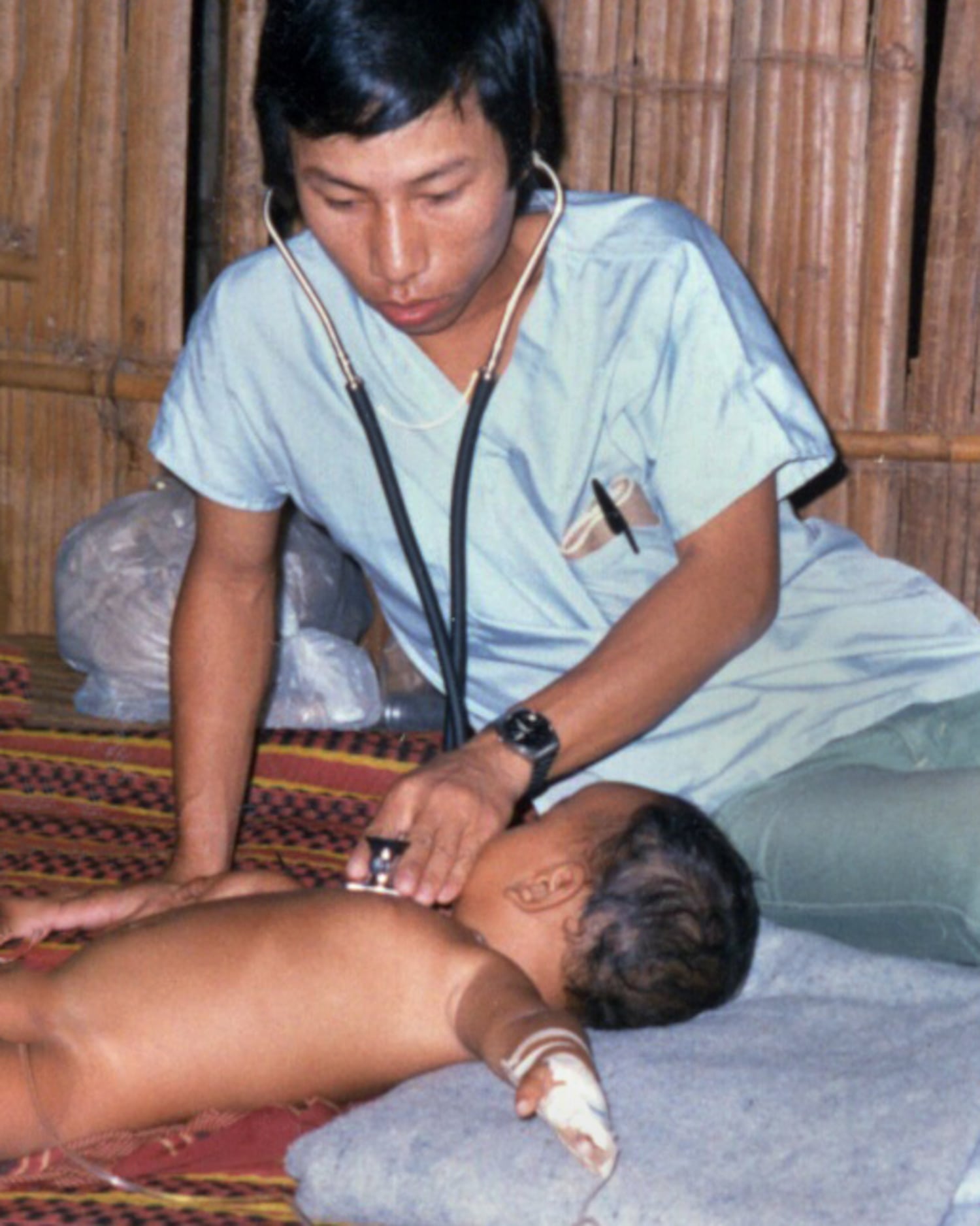

After the Khmer Rouge was driven from power in 1979, Sok Ry lived for a decade in a refugee camp on the Thai-Cambodian border. He earned his high school diploma and was trained as a medic.

He worked in the camp under an American doctor, and eventually found a new home in the United States. A scholarship earned him a law degree, and a master’s degree in international studies followed. Now, he is a senior editor with RFA’s Khmer service.

When asked how he feels now about what he went through, Sok Ry says he still has a clear memory of the slow and painful deaths suffered by his parents.

“Normally, you give forgiveness to someone who admits their mistake or wrongdoing and asks for forgiveness,” he said. “But none of the Khmer Rouge leaders have done that.”

Edited by Matt Reed

This content originally appeared on Radio Free Asia and was authored by Ginny Stein for RFA.