Powys Castle and terraces from the southeast in fine weather, Powys, Wales. n.d. Photo: CC BY-SA 3.0.

Friday, Jan. 16, 2026: A getaway

The spectacle of America’s at first slow, then rapid descent into fascism is both irresistible and unavoidable – like the proverbial slow motion train crash. Here in the UK, the BBC is now all-Trump, all the time, with occasional breaks to report on the departure of leading politicians from benighted Tory-dom to the sunny lands of Reform U.K., Britain’s leading fascist party. Apart from Trump, the politician whose voice is heard most often on The Beeb is his epigone, Nigel Farage.

My wife Harriet and I need a break from media and the daily outrages of Trump and Farage, so we’ve decided to drive west, about 250 miles to visit the remote studio of a potter/sculptor I learned about, Charles Bound, near Welshpool, in Powys, the largest and least populated county in Wales. The trip by car takes about five hours. We’ll leave early on Sunday to give us time to first visit Powys Castle, the ancestral home of the Herbert family, now a property of the National Trust. I frankly doubt the getaway will ease my mind, but it may give me space and time to reflect for a while about things other than the ongoing catastrophe.

Sunday, January 18, 2026: Castle Powys

We didn’t at first realize we arrived. The driving rain obscured everything, and the castle is nestled on a hillside among trees and terraced gardens. But when I turned to park, there it was, a great, hulking, mass of red stone with round towers and crenelations. A castle! One thing didn’t fit, however: three rows of large windows with architraves vulnerable to medieval weaponry: battering rams, catapults, crossbows, and even slingshots! Sometime in the late 16th Century, the 13th C. castle must have been turned into a manor house. I imagined processions of knights in armor and then three centuries later, courtiers in doublets and women in long, flowing skirts; what we saw was British tourists in Barbour coats and Wellington boots, holding dogs on leads.

Pevsner described the interior of Powys Castle as “the most magnificent in Wales”; that may be true, but I found it dark and dreary. The 16th and 17th C. ceiling paintings were feeble imitations of Veronese, and the early 18th C. portraits – mostly of the Herbert family – were dolls heads on well-dressed, mannikin bodies. The British were good at drama and poetry, but terrible at painting until William Hogarth, Joshua Reynolds and Thomas Gainsborough came along in the middle of the century.

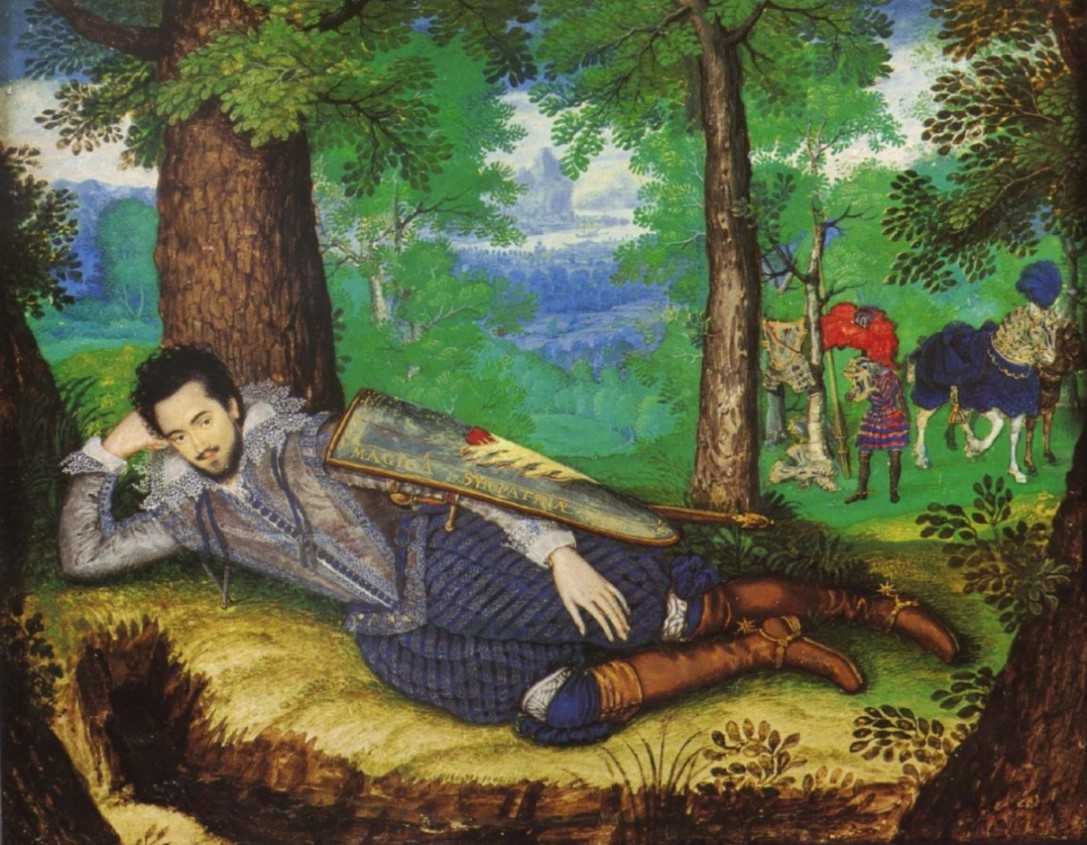

The exception that proves the rule at Castle Powys is Isaac Oliver’s miniature Portrait of Edward Herbert, 1st Baron of Cherbury (c. 1613-4). The baron is shown reclining on the ground beneath a tree, head propped up by right hand and bent arm. An armorial shield covers his side, but not his long-fingered left hand. His retinue is visible at right, and distant mountains are glimpsed between framing trees. Do we see, in Oliver’s portrait, an evocation of the renowned lover, duelist, philosopher and poet? In “An Ode Upon a Question Moved, Whether Love Should Continue Forever,” Herbert rejects the suggestion that humans must seek only the spiritual:

Isaac Oliver, Portrait of Edward Herbert, c. 1613-14. Powys Castle

No sure, for if none can ascend

Even to the visible degree

Of things created, how should we

The invisible comprehend?

The Baron’s doublet and chemise are unbuttoned at the top, opening him to “things created” – plants and trees, mountains and rivers, and the invisible lover at whom he longingly gazes. That attraction is as tangible as the world of nature:

Nor here on earth then, nor above,

Our good affection can impair,

For where God doth admit the fair,

Think you that he excludeth love?

There are few more beautiful or evocative portraits in Britain than Oliver’s.

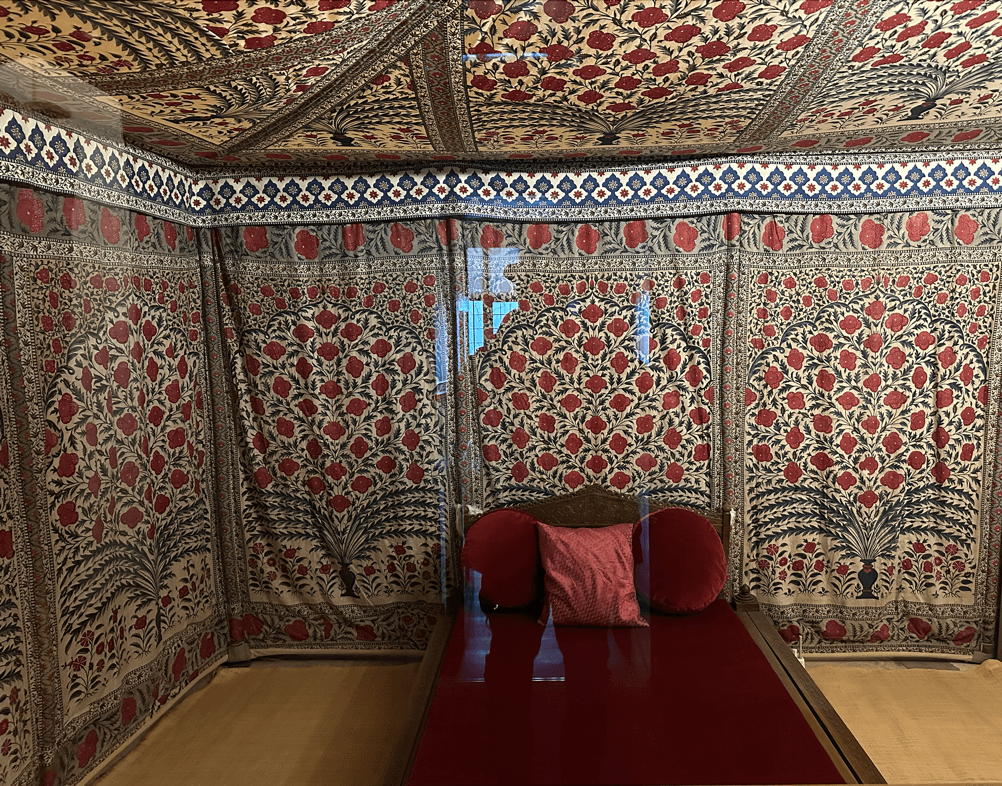

The other highlight of the Powys Castle collection is less romantic. It’s the imperial plunder amassed by Robert Clive (“Clive of India”) and his son Edward Clive. The former established British control of Bengal, via the East India Company, and the latter served as Governor of Madras and later parliamentarian from Shropshire. Edward’s marriage in 1784 to Henrietta Herbert made him Baron of Powys (she had the title; he had the money) and thus lord of the manor. The exhibited spolia include material seized by Clive (I) during the decisive Battle of Plassey (1757), and by Clive (II) following the killing of the enlightened Tīpū Sultān at the conclusion of the Fourth Anglo-Mysore War in 1799. There are Indian weapons, armor, and most remarkably, a bejeweled tiger’s head finial from the Sultan’s throne, Tipi’s traveling couch, or “palanquin,” and a field tent. The tent is made up of twelve, finely printed cotton (“chintz”) panels. Each shows a vase in the lower-middle, out of which radiate branches and red flowers on a creamy white field creating a peacock-like ensemble, perhaps a reference to the great Peacock Throne of the emperor Shah Jehan (early 17th C., now lost or destroyed).

Cotton tent panels, probably used by Tīpū Sultān, c. 1725-50. Castle Powys. Photo: The author.

Beginning in the 17th Century, British and European traders started to buy up fine, printed cotton from India to sell in home markets. More significantly, however, they shipped quantities of finished cotton to Africa to exchange for slaves, who in turn were sent to cotton plantations in the West Indies and later the United Sates. The East India Company and the British state reaped enormous revenues from the evil trade, enabling the latter to build the military strength necessary to eventually suppress or de-industrialize Indian cotton manufactures to the benefit of the cotton mills of Lankashire in England. Thus, was born modern industrial capitalism (and the British empire) out of Indian cotton, African slavery and the triangle trade. Imperialism – the military, political and bureaucratic domination of people, land and resources – is thus on full view at Powys Castle, in the display of gold, jewels, metalwork, furnishings and especially the cotton tent of Tīpū Sultān, looted by Edward Clive.

To clear our minds of these documents of barbarism, we’ll take a nice long hike tomorrow on Glyndŵr’s Way, named for the Welsh rebel leader Owain Glyndŵr, who in the early 15th Century, fought to free Wales from English, imperial rule. He succeeded for a while, but by the time of his disappearance or death in 1415, English authority was restored. Many Welsh today exclaim: “Mae’r frwydr yn parhau!” (“The struggle continues!”)

Monday, January 19, 2026: Middle of the night inspiration

Stirred by what I saw at Powys Castle, and thoughts about the recrudescent American empire (Venezuela and Greenland), I awoke at 2 a.m. with a solution for the Democratic party and the nation. I grabbed my phone from the nightstand and wrote the following in an email to myself:

Schumer and Jeffries and other Democratic Pary leaders, announce they will hold a news conference the following day at which they will make a major statement concerning the president’s health and the fate of the nation. It reads as follows:

“Donald Trump is mentally unfit to carry out his constitutionally mandated duty to ‘faithfully execute the laws’ of the United States, and ‘preserve, protect and defend the Constitution.’ We therefore demand the Vice President and cabinet officers immediately invoke the 25th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution and remove the president from office.

“We are aware of the gravity of our words but ask our fellow Americans to simply listen to President Trump’s announcements and observe his policies in Greenland, Venezuela, Iran, Gaza, and Minneapolis. They are sheer madness, unimaginable at any other time in our history, except perhaps during the age of “Manifest Destiny” in the late 19th Century, when the U.S. violently seized lands to build an overseas empire. Billionaires like J.P. Morgan, Henry C. Frick, John D. Rockefeller, and Andrew Carnegie ate oysters and drank champagne while the teeming masses lived in filthy, urban tenements or rural dirt farms. That’s the world of violence and squalor Trump is re-creating. It’s the product of mental illness, and it must be stopped now.”

I didn’t doubt an effort like this to oust Trump would fail. His cabinet loves (or fears) him too much to invoke the 25th Amendment. But here’s the genius of it: The initiative may have the effect of triggering the president to new, even more bizarre outbursts and threats, stirring greater public anxiety and organized protest. It seems to me Trump is walking on a psychological tight rope, and it would take very little provocation for him to lose his balance. And in politics at this level, there are no nets.

When I got up in the morning, I told Harriet about my brilliant idea. “What kind of plan is that?” she asked. “Isn’t it basically what Kamela Harris and Tim Walz ran on? Isn’t that what every pundit has been saying for years about Trump – that he’s nuts? Where has that got us?” She had a point. Crestfallen, I collected my toothbrush and razor from the hotel bathroom, put them in my backpack, and prepared to head off with Harriet to Geuffordd, Welshpool to meet the artist Charles Bound and his wife, Joy.

Tuesday, January 20, 2026: A visit to Charles Bound

My first love was Jackson Pollock.

By age 12, I had logged dozens of hours at the Museum of Modern Art in Manhattan and my favorite artwork was Pollock’s One: Number 31, 1950. Pollock was at the time (c.1968) still outré to middle-class culture consumers, but to me, he was the heroic artist who dared to throw a can of paint in the public’s face. Though long dead, I saw him as anti-war, anti-Johnson, anti-Nixon and anti-imperialist. While current orthodoxy sees Abstract Expressionism as expressive of Cold War ideology (American freedom beats communist conformism), the artists’ own beliefs and legacy are quite the contrary. Those who survived the 50’s, including Mark Rothko, Willem de Kooning, Barnett Newman, Philip Guston, Robert Motherwell and Norman Lewis, took a consistent, leftist, anti-racist, and anti-imperialist political path, and their works have ever since been endorsed by progressive artists across the global south, as David Craven revealed.

One: Number One, 1950 was endlessly absorbing. I’d follow a single skein as it meandered inside the picture space and out again, wrapped around or over other lines, spatters and drips, and tapered off. I’d try to understand what was painted first, second, and so on, reliving the process of its making – I always failed, everyone does. And I’d stand back, squint and try to take it in as a single pattern or totality – that’s also impossible. I admired the other Abstract Expressionists too but none so much as Pollock.

Charles Bound, three large plates atop a painted beam, Geuffordd, Welshpool, Powys. Photo: The author.

I mention this to help explain the impact upon me of works by Charles Bound when I first saw them at Contemporary Ceramics in London a few years ago. He’s a practitioner of what the critic John Coplans in 1966 called “Abstract Expressionism in ceramics,” that is, ceramics divorced from function, and freed to be as expressive, intuitive, and emotional as any painting or sculpture. Like Peter Voulkos (1924-2002), instigator of the American Clay Revolution, Bound (born 1939) rejects symmetry, refinement, functionalism, and what the Abstract Expressionist painter Barnet Newman called “the fetish of quality” and “perfect form.” His large, wood-fired stoneware plates are out of round, warped, pierced, punched, cut, dented, and burned. The thick necks of amphora are stretched to improbable lengths, pitted, scarred, spalled, encrusted with ash and shells, and blackened by heat and flames up to 1300∘ C. Bowls are coovered with scars and carbuncles, something like Raku (used in Japanese tea ceremonies), but more coarse, hard to hold in the hand, and impossible to put to the lips. Boxes, or chasses (box reliquaries) are more like neolithic dolmens hewn from quarries than precious casks for the bones of saints. Other works suggest columnar grave markers or funerary urns. Some ceramics are deconstructed teapots as big as dogs, composed of discarded or ill-matched slabs, shards, and stumps of clay.

Charles Bound, assortments of pots and posts. January 2026. Photo: The author

And then there are the pure sculptures, some on wooden pedestals, that are both referential and not: An oval mass of blackened clay is a head – in the right light, you can just see eyes, mouth and crooked nose, like an aged prizefighter’s face. Another is a horizontal hunk of clay, flattened but thick enough to stand on its side, with rectangular notches cut at the bottom left and right, and a hole near the top left; you can see in it if you wish, the form of a rhino. One sculpture I admire is convex on one side and concave on the other, with a vertical cavity stuffed with brick-shaped clay — like a punch in the mouth. There are dozens (perhaps hundreds) of works here of similar quality.

Charles Bound, Untitled, n.d. Photo: The author.

Bound is a tall, gangly man with a white beard and shock of hair recalling Sterling Hayden in The Long Goodbye (1973) or Gregory Peck’s Ahab in Moby Dick (1956). His agility is now slightly hindered by a banged-up leg and single crutch (I wondered if a sperm whale took a bite from it), but he easily scampered up and down the stone steps of his barns and into the shed that houses a massive, Anagama-style brick kiln that looks like a barrel-vaulted cave. Hung on the exterior of some barn walls were his large plates, like hex signs. Standing or leaning against them were amphoras or urns the size of middle school children. Smaller pots and pottery fragments were visible almost everywhere.

Charles Bound, assorted torsos and urns, n.d. Photo: The author

Over lunch prepared by his wife Joy (also a fine potter), Charles told us about himself: early rebellion against a privileged upbringing on Manhattan’s upper East Side and Westchester; brief enrollment at Occidental College in Los Angles in 1959 (coincidentally, I taught there 25 years later); first marriage and inability to join the Peace Corps because of his wife’s pregnancy; work and travels in Nigeria and later Kenya; appreciation for Ife and Benin bronzes, as well as vernacular African pottery, such as by the Mbeere, Tharaka, and Tigania communities; influence of Hans Coper’s Cycladic vases; and affinity for Japanese, Edo period Ige pottery, with its rustic and deformed shapes and surfaces. Good potters know the history of pottery.

We also discussed economic and cultural imperialism. During their time in Africa, Charles and Joy had little sympathy with the development officials they met. Their aloofness and noblesse oblige linked them to a long tradition of colonial administration and comprador exploitation and corruption. Bound registered to us his disgust at the looting of African sculpture by European and American collectors and curators, and the subsequent loss of cultural heritage following independence (Nigeria, 1960; Kenya (1963). He recalled a small museum of Ife (Yoruba) bronzes and shared with me – in a follow-up email — fragments of a prose-poem he wrote about it in the early 1970s:

…chickens disappearing to an insane safety under houses,

and the building – only different for having been painted

more recently than the others around it – that housed the

small residue of unearthed bronzes that hadn’t gone off

into some distant museum: like a family’s remains

after an unnatural disaster or a ravaging.

A decade after writing this, Charles and Joy moved to the U.K. and began making pottery at Jacob Kramer Art College (now Leeds Arts University). He reckoned with the achievements of Bernard Leach, Shoji Hamada and the tradition of British studio pottery, as well as the innovative American, Charles Fergus Binns and Warren Mackenzie. But almost from the beginning, he rejected the studio pottery movement for its insistence on function and embrace of refinement and sensuous beauty: tenmoku and celadon glazes, painting or pouring slip to create glassy surfaces, impossibly slender bowls (Lucie Rie), and reduction firing for strong colors and durability. Bound learned about Voulkos from magazines and books, and gradually discovered for himself the joy and freedom of “whacking something thrown, [and] picking up and reusing parts of something that collapsed.” Living in England, he was discovering, in a sense, his own New York roots; He was becoming a latter-day Abstract Expressionist. That awakening, Bound now reflects, came with its own political contradictions:

Certainly, that particular American assertiveness, however muted/suppressed, the assumption of right that comes with the passport, has always been part of my baggage. Though aware of the work of Voulkos & Co, what evolved with me was primarily the engagement with a material (technically, aesthetically) in combination with what else was going on, like having a workshop/kiln on a farm where I helped out as was feasible, seeing varied ways of dealing with problems and finding solutions.

Willem de Kooning, the Abstract Expressionist artist Bound specially admires, said as the war against Vietnam intensified: “It’s a certain burden, this American-ness.” Over 50 years later, Bound still feels this burden. His art remains rebarbative, hard for contemporary clay culture to accept. Bound sells his ceramics, here and there, and has shown in several significant individual and group shows. He has a few contemporaries who share his vision, and some younger artists following his path. His pottery is in the collection of the Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge and other institutions. But at 86, Bound no longer expect fame or fortune for his work, if he ever did. It’s enough for him to practice his craft — throwing, punching, kneading, caressing, pounding and stacking clay; then firing it and seeing forms spring to life.

Tuesday, Jan. 27, 2026: State of the empire

A week has passed since our trip to Wales. In that time, Davos has come and gone, the threat to invade Greenland has (at least for now) subsided, tariffs levels are where they were before, NATO is not (yet) dissolved, and another citizen has been murdered by ICE/Freikorps in Minneapolis. Trump is trying to figure out who to blame for the immigration chaos and violence, and the Democrats are trying to work out the political pros and cons of another government shutdown. The murders in Gaza continue as do deaths on both sides of Russia’s war against Ukraine. Vaccines are down and global warming is up. Medical insurance costs in the U.S. are rising, and employment is falling. In the U.K., Keir Starmer remains almost as unpopular as the former, 49-day Tory Prime Minister and punch-line, Liz Truss. Farage has now collected eight trophy-heads from the Conservatives and his goal of consolidating the right in advance of the next general election three-years from now is advancing with speed. Good to be home.

The post Diary Entries: Art and Empire appeared first on CounterPunch.org.

This content originally appeared on CounterPunch.org and was authored by Stephen F. Eisenman.