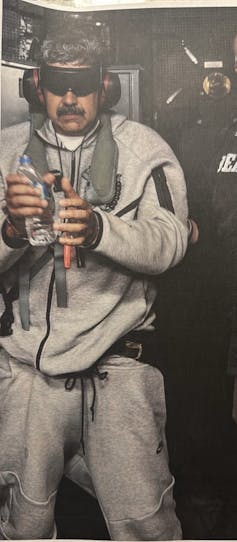

An image of a captured Nicolás Maduro released by President Donald Trump on social media.

An image of a captured Nicolás Maduro released by President Donald Trump on social media.

Truth Social

In the dead of night during the holidays, the United States launched an operation inside a Latin American country, intent on seizing its leader on the pretext that he is wanted in U.S. courts on drug charges.

The date was Dec. 20, 1989, the country was Panama, and the wanted man was General Manuel Noriega.

Many people in the Americas waking up on Jan. 3, 2026, may have been feeling a sense of déjà vu.

Images of dark U.S. helicopters flying over a Latin American capital seemed, until recently, like a bygone relic of American imperialism – incongruous since the end of the Cold War.

But the seizure of Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro, along with his wife, Cilia Flores, recalls an earlier era of U.S. foreign policy.

U.S. President Donald Trump announced that, in an overnight operation, U.S. troops captured and spirited the couple out of Caracas, the Venezuelan capital. It followed what Trump described as an “extraordinary military operation” involving air, land and sea forces.

Maduro and his wife were flown to New York to face drug charges. While Maduro was indicted in 2020 on charges that he led a narco-terrorism operation, his wife was only added in a fresh indictment that also included four other named Venezuelans.

Secretary of State Marco Rubio said he “anticipates no further action” in Venezuela; Trump later said the he wasn’t afraid of American “boots on the ground.”

Whatever happens, as an expert on U.S.-Latin American relations, I see the U.S. operation in Venezuela as a clear break from the recent past. The seizure of a foreign leader – albeit one who clung to power through dubious electoral means – amounts to a form of ad hoc imperialism, a blatant sign of the Trump administration’s aggressive but unfocused might-makes-right approach to Latin America.

It eschews the diplomatic approach that has been the hallmark of inter-American relations for decades, really since the fall of the Soviet Union in the early 1990s took away the ideological grab over potential spheres of influence in the region.

Instead, it reverts to an earlier period when gunboats — yesteryear’s choppers — sought to achieve U.S. political aims in a neighboring region that American officials treated as the “American lake” – as one World War II Navy officer referred to the Caribbean.

Breaking with precedent

The renaming of the Gulf of Mexico as the “Gulf of America” – one of the earliest acts of the second Trump administration – fits this new policy pivot.

But in key ways, there is no precedent to the Trump administration’s operation to remove Maduro.

Never before has the U.S. military directly intervened in South America to effect regime change. All of Washington’s previous direct actions were in smaller, closer countries in Central America or the Caribbean.

The U.S. intervened often in Mexico but never decapitated its leadership directly or took over the entire country. In South America, interventions tended to be indirect: Lyndon Johnson had a backup plan in case the 1964 coup in Brazil did not succeed (it did); Richard Nixon undermined the socialist government in Chile from 1970 on but did not orchestrate the coup against President Salvador Allende in 1973.

And while Secretary of State Henry Kissinger – the architect of U.S. foreign policy under Nixon and his successor, Gerald Ford – and others encouraged repression against leftists throughout the 1970s, they held back from taking a direct part in it.

A post-Maduro plan?

U.S. officials long viewed South American countries as too far away, too big and too independent to call for direct intervention.

Apparently, Trump’s officials paid that historical demarcation little heed.

What is to happen to Venezuela after Maduro? Taking him into U.S. custody lays bare that the primary goal of a monthslong campaign of American military attacking alleged drug ships and oil tankers was always likely regime change, rather than making any real dent in the amount of illegal drugs reaching U.S. shores. As it is, next to no fentanyl leaves Venezuela, and most Venezuelan cocaine heads to Europe, anyway.

What will preoccupy many regional governments in Latin America, and policy experts in Washington, is whether the White House has considered the consequences to this latest escalation.

Trump no doubt wants to avoid another Iraq War disaster, and as such he will want to limit any ongoing U.S. military and law enforcement presence. But typically, a U.S. force changing a Latin American regime has had to stay on the ground to install a friendly leader and maybe oversee a stable transition or elections.

Simply plucking Maduro out of Caracas does not do that. The Venezuela constitution says that his vice president is to take over. And Vice President Delcy Rodriguez, who is demanding proof of life of her president, is no anti-Maduro figure.

Regime change would require installing those who legitimately won the 2024 election, and they are assuredly who Rubio wants installed next in Miraflores Palace.

Conflicting demands

With Trump weighing the demands of two groups – anti-leftist hawks in Washington and an anti-interventionist base of MAGA supporters – a power struggle in Washington could emerge. It will be decided by men who may have overlapping but different reasons for action in Venezuela: Rubio, who wants to burnish his image as an anti-communist bringer of democracy abroad; Trump, a transactional leader who seemingly has eyes on Venezuela’s oil; and Secretary of Defense Pete Hegseth, who has shown a desire to flex America’s military muscle.

What exactly is the hierarchy of these goals? We might soon find out. But either way, a Rubicon has been crossed by the Trump administration. Decades of U.S. policy toward neighbors in the south have been ripped up.

The capture of Maduro could displace millions more Venezuelans and destabilize neighboring countries – certainly it will affect their relationship with Washington. And while the operation to remove Maduro was clearly thought out with military precision, the concern is that less attention has been paid to an equally important aspect: what happens next.

“We’re going to run the country” until a “safe, proper and judicious transition” occurs, the Trump promised. But that is easier said than done.![]()

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

The post A Predawn Op in Latin America? The US has Been Here Before, But the Seizure of Venezuela’s Maduro is Still Unprecedented appeared first on CounterPunch.org.

This content originally appeared on CounterPunch.org and was authored by Alan McPherson.