Janine Jackson interviewed Free Press’s Joseph Torres about the FCC and structural racism for the August 22, 2025, episode of CounterSpin. This is a lightly edited transcript.

(Verso Books, 2012)

Janine Jackson: CounterSpin listeners don’t need to be reminded of how central journalism is to everything we care about. Authoritarian leaders want to silence even half-awake news media, because information is so important to people’s understanding of the world, and how we might change it.

It’s also important to see, as on many issues, that Donald Trump didn’t invent bad, racist, anti-democracy media, or the legal landscape that allows it to thrive. As on other issues, there’s a history to understand and contend with if we’re serious about the goal of growing responsive, inclusive, intelligent news. And that history includes hope, as well as a lot of harm, much like the country itself.

Joseph Torres is senior advisor for reparative policy and programs at the group Free Press, co-creator with Collette Watson of the project Media 2070, and he’s co-author, with Juan Gonzalez, of the crucial book News for All the People: The Epic Story of Race and the American Media. He joins us now by phone. Welcome back to CounterSpin, Joseph Torres.

Joseph Torres: Yeah, Janine, thank you. Thank you for having me.

JJ: Well, I’m not saying that we aren’t in special times. Trump is daylight extorting from media corporations: “I give you the regulations you want, you give me the coverage I want.”

But for a lot of folks in 2025, it seems like the answer is government regulation in the service of the public good. And I think that sounds a lot better if you don’t understand how it’s worked up until now.

So in 2025, what should we know about the FCC, the ostensible defender of the public in the media world? What should we know about the FCC and Black and brown people?

Brendan Carr

JT: The current Federal Communications Commission, and its chairman, a man named Brendan Carr, are basically a part of Trump’s overall plan, overall scheme. The Trump administration—the far right, if you want to call them that—has now captured the presidency. It’s basically the ideology that is fueling this current moment of trying to undo all the gains that have been made for this period of 60-plus years, where equal protection rights in the 14th Amendment, and other civil and human rights, were extended to contend with the history of racial segregation in this country, and the history of racial subjugation in this country, starting from the very founding, and the system that’s been in place that resulted in enslavement of Black folks, and the land theft and genocide of Native American communities. And media has always played a critical role in this project of racial hierarchy.

And so the Federal Communications Commission today is trying, as part of Trump’s agenda, to roll back the very protections that were won over the past 60 years, as a way to consolidate power. The FCC is playing a critical role in that, because media is a place where the public understands what’s going on, and also derives meaning from, to understand the circumstances that they’re dealing with. Even though our media system has never truly shared the immediate information needs of Black folks and other people of color. (I’m being very kind by saying that.)

The FCC is rolling back, pushing companies to roll back their commitments to DEI, but really, it’s saying the presence of Black and brown people within institutions represents something inherently illegal or unlawfully gained. We got to get rid of any kind of programming, and the presence of Black and brown journalists or other content creators in the institutions; we cannot be trying to actually increase the presence of Black and brown people in the institutions.

And Janine, you and I, we’ve talked about it for years, these companies have never really sufficiently addressed what we need, our communities, the information needs they need to service. DEI commitments were actually committed to–and we could talk about our troubles with DEI, too–but after the George Floyd uprising, because these companies had not been serving those. But in order to have an authoritarian regime, you have to continue to ensure our voices are not heard.

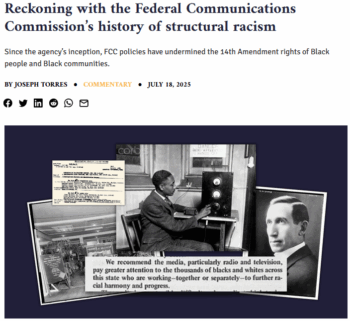

Objective Journalism (7/18/25)

This traces back to this recent essay I wrote, which is basically how, even though the FCC was created in 1934, [and] its mission is media policies to serve the public interest, you didn’t have to consider the public interest obligations of Black folks in 1934, because the 14th Amendment that was passed during Reconstruction didn’t exist then, because of Plessy v. Ferguson and Jim Crow racism and all the racial violence that was happening during this period. You didn’t have to consider the public interest obligations for Black folks, because there was no equal protection rights. The equal protection under law was not being enforced at that time.

And so this is why we created a segregated media system, in a sense. Well, segregated media system is actually being too kind, we created a white-controlled media system, where white folks controlled all the broadcast stations, when the FCC was actually providing licenses to media companies that supported segregation, or profited off of segregation. And we have not contended with that history.

JJ: And I think a lot of folks don’t understand. They imagine that there was a time when media supported the public interest, and then somewhere along the line, that got perverted or confused, and you need to say: What you think of as the “public interest” was not something that included Black and brown people. So these ideas that you imagine you’re going to “get back to,” where everything was fair, you need to interrogate that understanding. You need to complicate that understanding, because that’s not how it actually worked.

And this is a conversation we always have, as Black media critics, as Black and brown people concerned with media, folks who are very smart understand top-down bias, and they understand capitalism and corporate capitalism bias, but they still want to say, “It’s not Black and white, it’s green.” And then we have to show up and say, “Yeah, it’s still actually Black and white.” You still have to look at that piece of it, because that piece never went away.

Josephus Daniels

JT: Yeah, I mean, just to illustrate that point, just to give examples, in the essay I tried to point out that the government’s role in the birth of commercial radio really started to accelerate during World War I, when the US Navy was investing heavily in wireless technology. The head of the US Navy, the secretary of the Navy, was a man named Josephus Daniels, and this is under Woodrow Wilson’s administration.

And Josephus Daniels was a newspaper publisher, a powerful newspaper publisher. And in 1898, he owned the Raleigh News and Observer. And he helped to orchestrate a coup of the multiracial government that existed, that was formed following Civil War Reconstruction, to overthrow the multiracial government in Wilmington, North Carolina. And he worked hand in hand with the Democratic Party to orchestrate that. And he called his newspaper, the Raleigh News and Observer, to rally up support for the criminalization of Black folks, to overthrow the local government. And he called his paper the “militant voice of white supremacy.”

Now he is in charge in overseeing the development of commercial radio under Woodrow Wilson, with his devout white supremacist father who was a slaver, hosted Birth of a Nation at the White House, president of Princeton University. In his own writings, he talks about, in extremely racist terms, his hatred of Reconstruction, and the idea that Black people would actually be in some sort of position of power during Reconstruction. So he detested the idea of growing Black power in the South through the Reconstruction.

So these are the folks who developed commercial radio.

Then, following World War I, the US wanted to make sure that radio remained in control of the US. There was the Marconi radio company, that was the British-based company, and the foreign ownership broadcast stations that would become radio stations in the United States.

And so they created the Radio Corporation of America. First they tried to have the government be able to control radio, but then they compromised–Congress rebuffed that effort, and they created the Radio Corporation of America, RCA, where there was a trust, called the Radio Trust, where folks who were concretely involved in wireless radio technology all got together, and colluded together, helped to create the birth of commercial radio in this country.

And then Herbert Hoover, who was the president of the United States in 1929, but was the head of the Department of Commerce for most of the 1920s, oversaw the licensing of radio stations. But he also was a person who was using his department to promote racial housing segregation in the country.

So these are some of the forces, critical central forces, powerful forces, who were behind, not just the birth of commercial radio, but what would become the Federal Radio Commission in 1927. And then the first chairman of the Federal Communications Commission, who was the last chairman of the Federal Radio Commission—the Federal Radio Commission from 1927 to 1934 became the Federal Communication Commission when it was formed. But the chairman sat on the Mississippi Supreme Court, appointed by Governor Bilbo, who was one of the most notorious white supremacist governors, and later senators, to serve in any kind of public office.

He was a member of the Mississippi Supreme Court for about eight years. And so the idea that he’s the first chairman of the Federal Communications Commission…. I didn’t write in this piece, but there were other commissioners who were very devoted to white supremacy, or were mayor of, I believe, Charlotte, North Carolina, which was a segregated city. And so these white supremacists, in Wilson and the publisher Josephus Daniels of the Raleigh News and Observer, these are the forces who helped to birth commercial radio.

Joseph Torres: “We have not reconciled the history of… how government regulation was just reinforcing the racial apartheid that exists in our country.”

And there were Black folks who were trying to get broadcast stations. There was a lot of interest in the Black community in broadcasting, and becoming broadcast owners. And so the whole point of it is that we have not reconciled the history of how our broadcast, not just institutions, for sure, but how government regulation was just reinforcing the racial apartheid that exists in our country.

And then it took until the 1960s, to the Civil Rights Movement, to this famous case in Jackson, Mississippi, WLBT, where the civil rights activists in Jackson, along with the United Church of Christ, were able to successfully challenge the broadcast license for a racist station in Jackson, that opened the door to give US citizens rights to actually challenge FCC policy, to where we saw Black and Latino and Asian American, Indigenous groups, filing license challenges in the late 1960s and 1970s, all over the country, that resulted, really, in the first wave of any kind of significant integration of our broadcast systems.

And that’s the fight we’ve been on for the past 50-plus years, trying to integrate these systems. And this is what the FCC is trying to undo. Again, that integration of these systems hasn’t been sufficient. We’ve been fighting to integrate these systems, and we can have an argument whether we’re integrating these systems that haven’t served our needs. But at the same time, the hope of ownership dwindles away, the idea that we can own broadcast stations dwindles away, because of the massive consolidation of our media system that starts happening in the 1980s, that continues through the 1996 Telecom Act, and all this massive consolidation that’s still happening now, that even more consolidation that’s going to further entrench the de facto media apartheid system.

JJ: Absolutely. And folks will know about those increased efforts at consolidation, where companies are what we call “skating where the puck’s going to be.” What they’re trying to do might be illegal right now, in terms of consolidating companies, but they’re pretty sure they’re going to get laws in their favor, so they’re going ahead and doing it anyway. And that is also not new to the Trump administration.

So I want to direct folks to your piece that we’re talking about at ObjectiveJournalism.org. And I want to just underscore what you’re saying: It’s history, it’s not rhetoric. It’s not like, if only Black and brown folks would’ve, could’ve tried something back in the day. We did. People did, and they were shut down repeatedly, officially. It’s not a question of “folks should have worked through appropriate channels” or “if folks had just built a better mouse trap, then maybe they could have won in the corporate world.” We’re still talking about deliberate racial discrimination. That’s part of the story that we have to tell, and you’re just not going to understand it if you can’t accept that that’s part of it.

JT: And in the piece I wrote, in 1927, there was a Black newspaper in Detroit, a weekly newspaper, that was saying, “Hey, we have to own our own radio stations. We can’t tell our stories and advocate for our community through the white man’s radio.”

In 1930, the Kansas City American, a Black newspaper as well, actually applied for a license to build a radio station, and they were denied. And there were other stations, in Hawaii, someone applied for a license to serve Japanese languages, serving the Italian communities or an Italian-language station. But these applications were denied, and it was basically like, “Hey, your community’s already being served by a radio station that exists.” Again, this is also a time with really, a lot like now, anti-immigrant sentiment in the country.

So this effort in the ’60s to try to desegregate our media system, that included to try to get increased radio ownership, it was always a recognition of the importance of ownership that was understood. In 1914, 1915, early 1900s, there were Black radio clubs being formed across the country to teach ourselves wireless communication technology, to be able to build their own radio sets, listen to broadcasts broadcasting from other parts of the country.

Rufus P. Turner

The first Black person—this is something that’s not too well-known, I only learned about it in the past couple of years. That’s the point with history. We’re still learning things we should know are buried in history, right?—there was a teenager named Rufus P. Turner, who was a real genius, who created the world’s smallest radio set. He was really received well in the radio community for his genius. At only 17 years old, he got the ability to be the first commercial radio station, a low-power station to serve the DC area in the mid-1920s. But this was before the official birth of commercial broadcasting, and the regulations around commercial broadcasting. And newspapers, and Black newspapers in Washington, DC, were hailing this young man as a genius.

The point is, we still don’t have the full story of how our communities were really embracing this new technology, because the story of the history of the FCC is often not told through this vantage point. There’s not too many folks who are studying this history from the issue of race and racial subjugation. But understanding that history, and understanding what is happening today—the circumstances are different in essence, but the DNA of how the system was created, we still have not resolved that.

So this FCC chairman can easily call for companies to get rid of their DEI commitments. And companies are able to say, of course, because we’re furthering our bottom line. And the idea for major companies, they’re not committed to our community, they’re committed to the bottom line.

Because, as you know, Janine, it’s hard to create any kind of lasting change with anti-Black narratives, and narratives against other people of color, that criminalize you, dehumanize you. And you see all this overt racism happening now, and just the cruelty of it is because these narratives have continued to work to dehumanize us. And when you dehumanize us, you can actually do anything to us.

And so I don’t know how we fight to get out of the situation we are at without addressing the history of anti-Black racism, and not just institutional, but structural. This is what the essay is attempting to do, is to place the media at the center of the current struggle that our communities have been fighting for a long time, to ensure that civil and human rights, especially the 14th Amendment, continue to be something to expand the possibility of redress.

JJ: Absolutely. Well, this is an ongoing conversation; we’ll just pause it for now.

We’ve been speaking with Joseph Torres; he’s senior advisor for reparative policy and programs at Free Press, co-creator of Media 2070 and co-author of News for All the People. His article, “Reckoning With the Federal Communication Commission’s History of Structural Racism,” is online at ObjectiveJournalism.org. Thank you, Joe Torres, for joining us this week on CounterSpin.

JT: Thank you, Janine, so much for having me.

This content originally appeared on FAIR and was authored by Janine Jackson.