There is an inclination to recoil from prognostications of doom, not merely because such prognostications have often been wrong but also because they are often right. Human worlds have ended time and again. Yet, as we know with the benefit of hindsight, such endings are not permanent and in some cases have even ultimately given birth to better and more humane worlds. Not only can we not be certain about the future, but fixating on it can turn us into passive spectators in perpetual waiting, forfeiting our agency in the here and now. As Raoul Vaneigem has noted, whatever the future will be, it will be wholly natural to us, as it will be ours. The task then is not to issue sky-is-falling jeremiads about the coming apocalypse but to denaturalize the present, showing that the sky has already fallen and that the apocalypse is in fact already here.

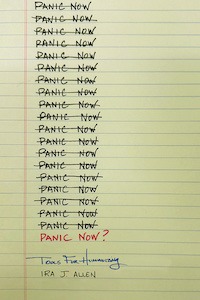

Ira Allen’s Panic Now? (University of Tennessee Press, 2024) seeks to do just this. In a finely argued and persuasive account of four existential crises and how best to respond to them, Allen shows that the world as we know it has already entered a process of what he calls staggered collapse and that, critically, there is not only no political will (an obvious point) but also no technological capacity (a somewhat less obvious one) to save it. Focusing on climate change, mass extinction, novel chemicals, and AI, Allen moreover argues that the political economic system of Carbon, Capitalism, and Colonialism (or CaCaCo for short) that has produced these crises is not worth saving in the first place. Instead, it is time to come to grips with the fact that the current world system is not salvageable and to begin planning for the next one, prefiguring it in the values and organizational principles we might practice today.

Allen’s description of the four crises (he notes that there are of course many more) is convincing and useful. Of particular interest here, in part due to its relative novelty, is the human disaster that is AI. Karen Hao and others have described some of the most obvious problems with AI. For one, AI is reliant on horrifying amounts of freshwater and other resources (those sociology essays won’t write themselves!). And, as others have observed, AI represents an ominous new phase in the deskilling

that capitalism has been subjecting us to for centuries. In this case, though, what is being deskilled isn’t our capacity to make shoes or belts but our capacity to think. Or, more precisely, since AI doesn’t think at all, our capacity to think is being replaced by what Allen helpfully terms automated intellection. As we know from previous periods of deskilling, humans will not only unlearn powers and abilities that we have cultivated from as far back as we can remember, but we will also be transformed into mere appendages of our latest machine masters — adopting their form as we become vehicles to their purpose (i.e., maximized capital accumulation based on the exploitation of our labor). And just as with dishwashers, washing machines, cars, and phones, the time-saving benefits of AI will be ineluctably funneled toward greater economic productivity for capital through both increased personal consumption and broader societal 24/7 exploitation (a cycle illustrated in Ruth Cowan’s More Work for Mother). The ensuing economic crisis resulting from AI’s reduction of labor-extracted surplus value will just be the winky face emoticon at the end of the AI death sentence. Any notion of an “upside” to AI is, in so many words, venture capital bullshit.

Allen, though, is particularly concerned with the harrowing way in which AI saves time, how “generative AI will dispose us, arrange our ways of being and meaning and acting…” in which humans will be at the receiving end of the “machinic ultra-efficiency” of a literally inhuman culture. While humans have long been at the receiving end of ubiquitous commercial advertising, which directs our thoughts and feelings for its own purposes, the subordination of human consciousness to AI’s cultural symbols represents a new frontier in the history of the domination and degradation of our species. It is one thing to give a Hallmark card to a loved one. We read and might even repeat and come to believe the treacly canned message. But it is something else to convey the words of a machine and to tell your loved ones, and yourself, that the machine’s words are yours, that its pseudo-thoughts are in effect your non-thoughts. AI, Allen suggests, is then not merely the most recent iteration of deskilled labor but, in subordinating humans to automated intellection machinery in all aspects of life including our social bonds, a ruthless assault on humanness itself.

Accordingly, the book argues, we ought to panic, not just about AI but in response to the entire polycrisis that is currently ending the world as we know it. Allen takes us on an etymological tour of the word, illustrating its disruptive radical origins by looking at the strange role of the deity Pan. Panic is not necessarily running around like a chicken with its head cut off, but can be a collective disruption of a movement going in the wrong direction. That is, Allen insists that we “panic wisely” and, via a nice reading of Rachel Carson, turn toward wonder, out of which can come a better world. Panic’s antithesis, by contrast, is hope, which is not only impractical but profoundly depoliticizing, a “therapeutic dose of poison” leading us to falsely believe that our system is capable of or warrants salvation.

At the same time, Allen rejects doomism and embarks on a discussion of prefigurative politics focusing on four practices: solidarities, sustained disruptions (“seeding the possibility for something other to both the barbarism of continuity and the barbarism of acceleration”), novelties, and archaism: “dispositions” that can, Allen argues, lead to another world via revolutionizing, or “humanizing,” our species. There is much practical and philosophical wisdom here, such as Allen’s discussion of the indigenous city of Cahokia and the role of archaic practices including ceremony. The discussion is nevertheless not always convincing. Prefigurative politics of course have a long legacy and it would have been useful to more closely examine previous failures (including the inevitable fact of police repression) and why the concept has been described by critics such as Alex Callinicos as “ultimately self-refuting.” It is also not clear how some of the specific prefigurative suggestions Allen provides — checking in on a neighbor, making consumer choices that reduce waste, supporting co-ops and the Writers’ Guild of America — are distinguishable from conventional liberal practices that can exist quite happily within CaCaCo. (In a different vein, Allen’s discussion of the inevitability of hierarchy could have been further developed by distinguishing hierarchy from power, a la Pierre Clastres’ Society Against the State).

More broadly, there is the problem of crisis itself. While Allen briefly addresses in the endnotes some criticisms of the concept of crisis, a more developed discussion of the modern history and epistemology of crisis might have further informed his analysis of our present. Marshall Berman has noted in All That Is Solid Melts Into Air that the disorientating and unending volatility of modern human existence, in which we perpetually feel the ground shifting under us, has in fact been consistently afflicting us since the modern world began around 1500, and Eric Hobsbawm has periodized the entire history of 1914-1945 as an age of catastrophe. It’s tricky then to fully distinguish the empirical fact that now the shit is really hitting the fan from not only history but also from some of the stories, with their frequently consumerist and regressive utility, we hear about crises. Allen in part gets around this problem by marshalling overwhelming scientific data showing that this world — the only one we’re living in right now — has in fact begun an irreversible transformation due to our polycrises. We’re going to panic sooner or later, so why not do it now, deliberately, while we have the opportunity to engage in a discussion of not merely ideal practices but the kind of values we would like to build the new world around. This, though, is not a Pascalian Wager. In walking away from one dying world, Allen rejects not only the absurd and self-serving tech optimism of billionaires but also Marx’s materialist observation that “Mankind always sets itself only such tasks as it can solve” and, it seems, even the dream of taking power through socialist revolution.

The book, then, lends itself to being supplemented by works with more historic focuses (it contains excellent notes and references, although I wish it had an index). One task might be to identify the ways in which our present crises are both unique and historical. Denaturalization has its purposes, but so does historicization. In either event, Allen does more than his fair share in advancing the discussion.

The post On Panic appeared first on CounterPunch.org.

This content originally appeared on CounterPunch.org and was authored by Joshua Sperber.