Peruvian journalist Gastón Medina Sotomayor did not hold back in his last TV news broadcast before he was shot dead this year. Addressing the viewers of Cadena Sur, his TV and radio station in the south-central city of Ica, Medina called local authorities “scoundrels” for buying defective garbage trucks. He criticized cost overruns for a new sports arena. And he called into question a police chief’s behavior after video emerged of a woman sipping brandy and listening to music in the chief’s office after hours.

“The only thing lacking was a light show to turn the police colonel’s office into a discotheque,” an outraged Medina told his viewers.

Medina’s full-throated fulminations against government corruption earned him a large following, local journalists told CPJ, but also made him the target of numerous threats.

After signing off from his daily program on Jan. 20, 2025, Medina, 60, was chatting with a friend outside Medina’s Ica home when a man on a motorcycle fired 11 shots at the journalist. Medina was struck in the thorax, wrist, and foot. He died at a hospital shortly afterwards.

Recalling the scene, Medina’s partner Nathalie Caico, who was also home at the time and is the mother of their 10-year-old son, told CPJ in a recent interview that the journalist always said that the only way to shut him up is “to kill me.”

Caico, who was wearing dark glasses and a black outfit in mourning for Medina, added: “Now the killers are happy because there is no one to expose all their corruption.”

Medina’s death sent shockwaves through the Peruvian press because he was the first journalist killed in Peru since 2019. Medina had received numerous death threats, and the public prosecutor in charge of the case says his killing may be related to his journalism. But so far, there has been little progress in determining why he was gunned down. So, like most journalist killings in Peru, CPJ defines the motive for Medina’s killing as unconfirmed – meaning that it was possibly work-related.

Impunity, retaliation, and fear

During a June meeting with officials from the Attorney General’s office in Lima, Carlos Lauria, executive director of the Inter American Press Association, warned that the lack of justice in such cases foments self-censorship by journalists and “sends a message to society that those who kill can continue to do so with impunity.”

The journalist community in Peru was still grieving Medina’s death when Raúl Celis López, a news show host on Radio Karibeña, was gunned down in the northwest jungle town of Iquitos on May 7. What’s more, the deadly violence came amid a growing government backlash against the press.

Peruvian President Dina Boluarte has lashed out at the media for its coverage of the country’s rising crime, democratic backsliding, and corruption scandals inside her administration. She even accused journalists of plotting against her in a speech in March. The following month, Boluarte signed a law requiring foreign-funded journalism organizations to list their activities in a government registry, a mechanism press advocacy groups fear could lead to censorship.

There have also been a slew of legislative initiatives, and lawsuits filed against journalists by public officials, along with smear campaigns by pro-government activists that aim to intimidate independent media, said Adriana León of the Institute for Press and Society (IPYS), a Lima-based press freedom group.

“All of this generates a lot of fear and concern,” León told CPJ. “The fact that two journalists have been killed in just the first half of this year is especially alarming.”

Becoming a community firebrand

Medina began his career in the 1980s as a radio DJ in Lima, then returned to his native Ica to manage a radio station. In 1995, he acquired his own station, transforming it into Cadena Sur, which now broadcasts in Ica and five outlying towns.

In addition to his two-hour morning TV program, Medina hosted a two-hour afternoon radio program and frequently posted news updates and his own biting commentary on social media. All this made him a well-known figure in Ica, so much so that supporters encouraged him to run for office. He finished third in the race for governor of the region of Ica in 2018 and was contemplating a run for congress as a populist, anti-corruption candidate at the time he was killed, Caico told CPJ.

As a journalist, Medina could be at times bombastic and unfair, colleagues said. Ica human rights activist Rosario Huayanca recalled how in the 1990s, as Peru’s army battled Shining Path guerrillas, the journalist labeled her a “terrorist” for her work defending families displaced by the fighting.

But Huayanca told CPJ that she came to respect his more recent reporting because Medina was one of the few journalists in Ica willing to publicly denounce wrongdoing.

By contrast, local authorities often pay journalists monthly stipends of 500 Peruvian sols ($140) or give jobs to their relatives in exchange for positive coverage, arrangements Medina frowned upon, said Carlos Caldas, president of Ica’s Regional Association of Peruvian Journalists.

“Gastón was very critical of this practice,” Caldas said. “He did what journalists are supposed to do: denounce corruption.”

As a result, Medina faced a near-constant backlash that point put Cadena Sur’s survival in jeopardy.

‘How can you live like this?’

After Medina accused the Ica’s governor’s wife of using state resources to run for congress, police confiscated Cadena Sur’s transmission equipment in an Oct. 27, 2020, raid on its offices, forcing the station off the air for three weeks.

Throughout 2022, Medina and Cadena Sur were targeted. A .38-caliber bullet and a hand-written note that said “Gastón Medina, you will die,” was found at the station entrance on February 23, 2022. Animal excrement was smeared on the station’s door, a dog carcass with a slit throat was left outside the office, and a man on a motorcycle threw an explosive that destroyed Cadena Sur’s entrance.

Another, anonymous, death threat came in November 2024, Caico said, but Medina did not report it because the journalist distrusted the police, who were frequent targets on his program. She added that Medina often broadcast from a home studio to avoid commuting to the station.

In an interview at the Cadena Sur office in Ica, which now has a massive front door of reinforced steel for better security, Pilar Hernández, Medina’s business partner at Cadena Sur and his wife from whom he was separated, said that in his final days, the journalist seemed tormented.

“I asked him: ‘How can you live like this?’” she said.

Trigoso told CPJ: “This was a very well-planned homicide.”

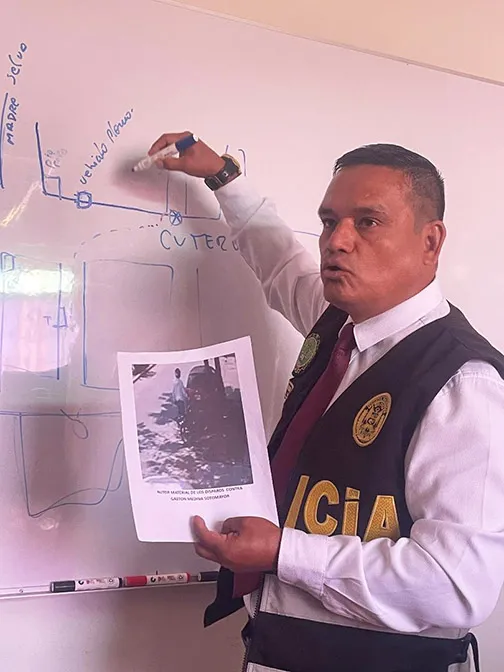

Through security camera footage, police determined that five people spied on Medina’s house and carried out the fatal January 20 attack. On May 16, agents arrested the alleged gunman, Pablo Javier Echevarría, a 28-year-old Venezuelan immigrant. But Col. Benjamin Trigoso, the Ica police investigations chief, said it was unclear who hired the hit squad.

Fighting for justice

Ányela Salazar, the public prosecutor in charge of the Medina case, told CPJ that most of the information she has gathered about the killing is confidential. But she acknowledged that, among various leads, she is investigating whether local government officials conspired to kill the journalist in retaliation for his reporting.

That may sound extreme, but in recent years, Ica’s politics have grown violent. A bodyguard for current Gov. Jorge Hurtado was shot dead at a campaign event in 2022, while the Ica state health director survived a shooting the following year.

In an interview, Deputy Governor Luz Canales told CPJ that corruption and mafia-style brutality plague the regional government, adding, “I don’t trust any of the officials here.”

Salazar has vowed to go after the masterminds in Medina’s killing. In the past, however, those who have ordered the killing of journalists in Peru have almost never faced justice, said León of IPYS. Only one of eight journalists in Peru found to have been murdered for their work has achieved full justice, CPJ data shows.

Many sources told CPJ that the journalist’s March 21, 2023, program may offer clues about why he was killed. In it, Medina spoke with Víctor Mere, an ex-convict with ties to the Ica state government. Mere claimed that he and Carlos Zegarra, the governor’s top aide, had plotted to kill the journalist – though Mere later denied it. Mere himself was shot dead on March 3, 2025.

Zegarra, whom Medina had often accused of corruption, told CPJ that he was not involved in killing the journalist and said authorities have not questioned him.

With Cadena Sur journalists no longer willing to scrutinize politicians out of fear, Medina’s death has left a gaping hole in the outlet’s coverage, said Hernández, the journalist’s business partner.

“No one calls out corruption out like Gastón did,” Hernández said as she stared at Medina’s vacant desk and dusty microphone. “With his death, they have silenced everyone.”

John Otis is CPJ’s Andes correspondent. Shanna Taco is a Peruvian journalist affiliated with the Institute for Press and Society.

This content originally appeared on Committee to Protect Journalists and was authored by John Otis.