In the tranquil hills of Nepal’s Gandaki province, where the land rises in its northern district of Mustang toward the border with Tibet, the pace of life has slowed for the last legion of the Tibetan armed resistance.

Now in their twilight years, these are the warriors who mounted a united campaign from the 1950s through to the mid-1970s against the Chinese occupation of their homeland. They live quiet, spiritual lives far removed from the days of gathering intelligence and ambushing Chinese military convoys.

Many of these fighters were trained by the CIA. They bear experiences that few outside their circle can fathom. Their stories are filled with code names, secret camps, clandestine border crossings, and survival in brutal conditions. They played a pivotal role in helping Tibet’s spiritual leader, the Dalai Lama, escape into exile.

Today they have a sedate existence. Most live in retirement homes, in settlements like Jampaling and Paljorling that are scattered around Nepal’s second largest city, Pokhara. A select, more affluent, few live around the capital Kathmandu.

But they have an important and urgent message they want to share with future generations, rooted in the beliefs that drove them when they took up arms up to seven decades ago: to stick together to defend the Tibetan way of life.

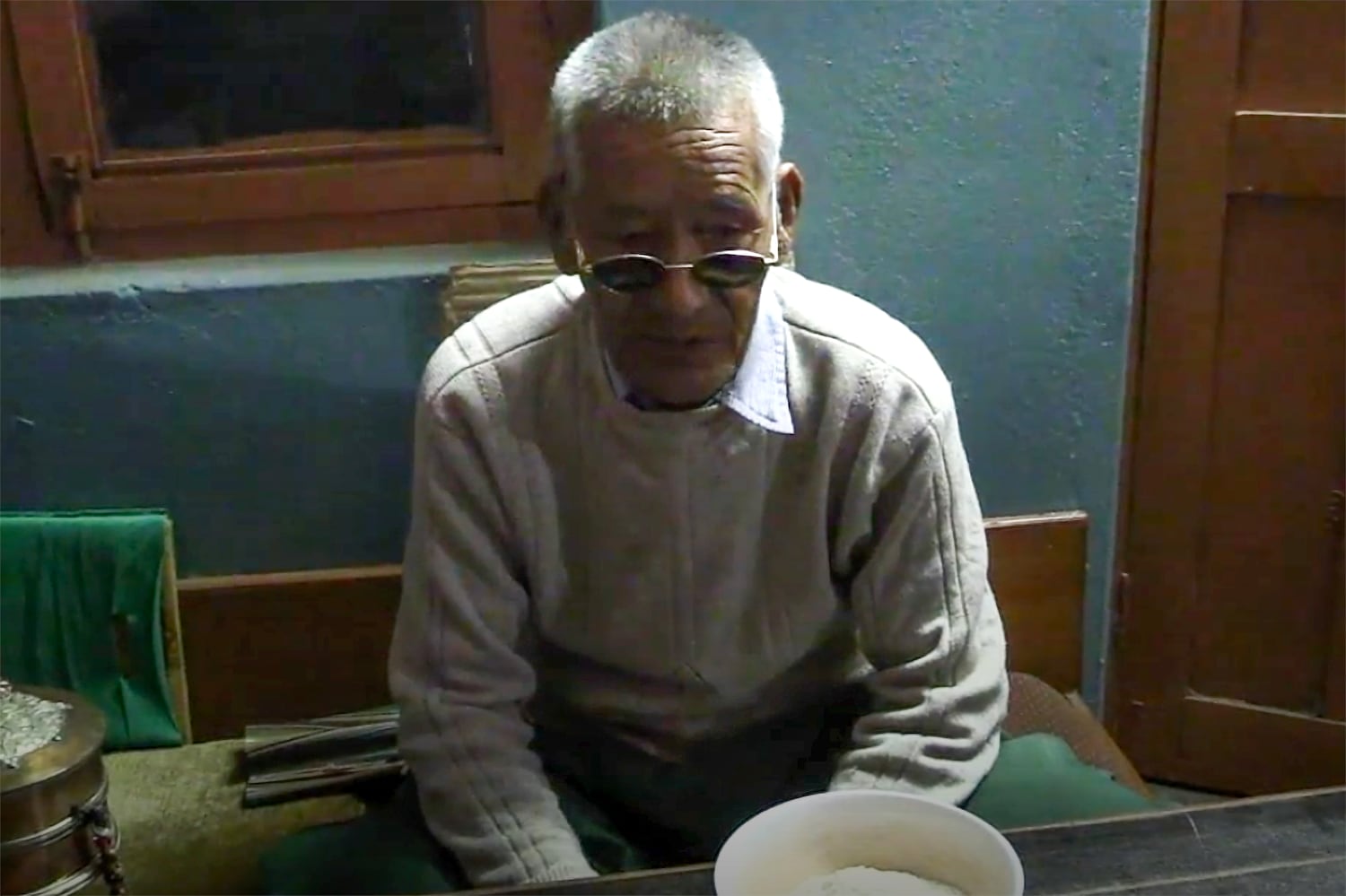

“The idea of ‘Tibet’ is no longer a question of geography — it’s about the resolve and readiness to sacrifice everything for the greater purpose of serving the cause,” said Ugen Tsering, 87, also known as Utse Ugen, one of the former fighters who now runs a successful Tibetan restaurant in the heart of Kathmandu’s bustling tourist district, Thamel.

As their numbers dwindle, the former resistance fighters are eager to share their little-known stories.

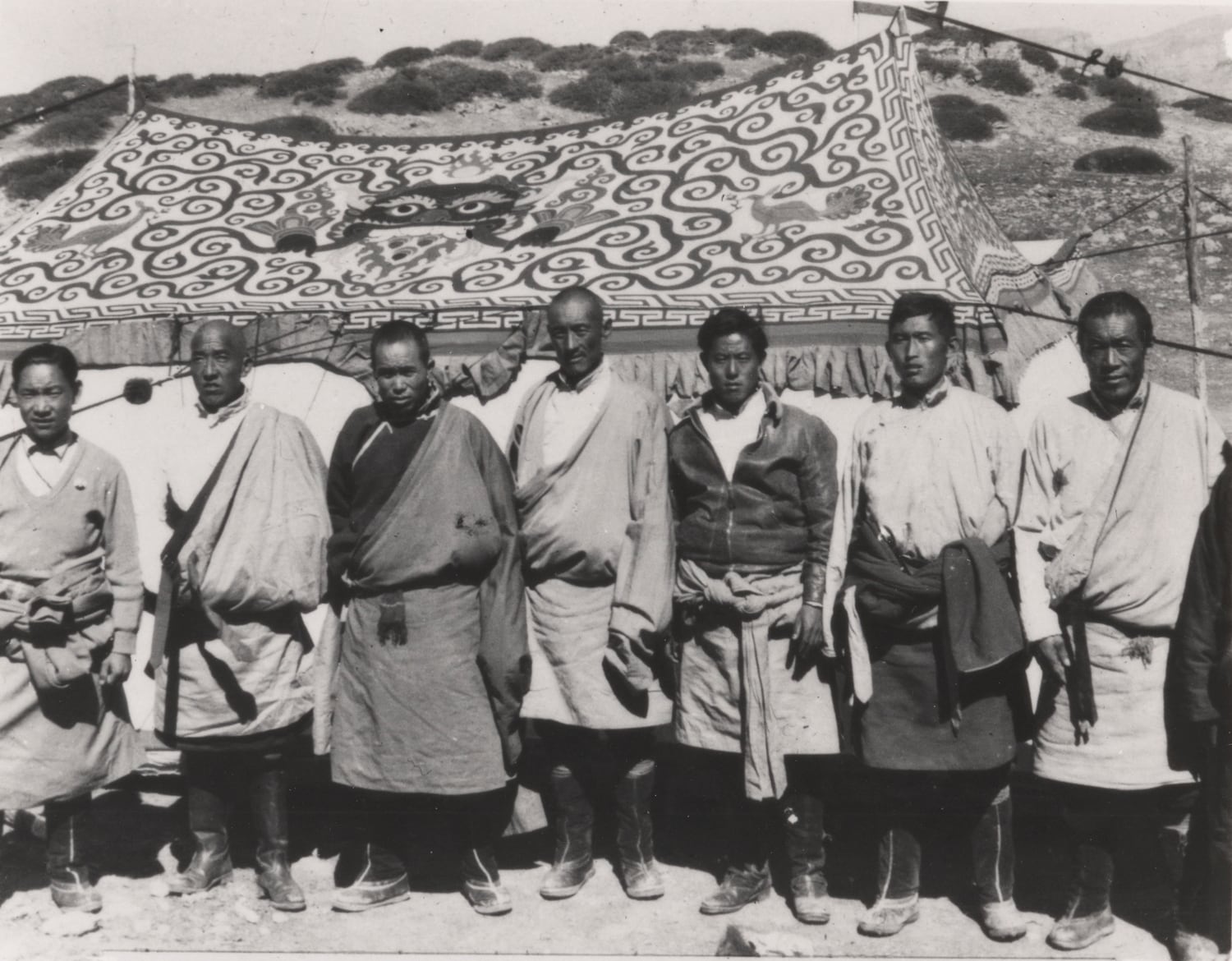

Their armed struggle against China began with a grassroots force, the Chushi Gangdruk or Four Rivers, Six Ranges, that was later known as the Tensung Dhanglang Magar, or the Voluntary Force for the Defense of Buddhism. The movement then received covert financing, training, and weaponry support from the CIA, which code-named the project ST CIRCUS – running it for over a decade from 1957 until U.S. support for the Tibetan resistance ended in 1969.

Ultimately, their goal to regain control of Tibet that had been occupied by China in the early 1950s was unrealized. But they had successes – not least in forming a movement that overcame regional, religious and linguistic differences that have often divided Tibetans who have inhabited the vast Tibetan plateau for millennia.

“There were young Tibetans from the three provinces (of U-Tsang, Kham, and Amdo) alongside us – all committed to the cause and willing to sacrifice our lives,” said Phenpo Gyaltsen, 93. “I never heard any distinctions being made based on our regions. The only message we ever received was that we are all the same and whether in joy or in suffering, we stand together.”

“Our generation is both unfortunate and fortunate,” said Ugen, referring to the first generation of Tibetans who witnessed China’s annexation of Tibet in 1950. “We faced tremendous difficulties in our time, but we also had the opportunity to take action and strive to overcome them.”

Ugen – code-named “Bob” – was one of the hundreds who received training at the secret training facility the CIA ran in Camp Hale, Colorado, in 1958-1964.

Hailing from the central Tibetan region of Gyangtse, Ugen was assigned in 1958 by Gyalo Thondup – the Dalai Lama’s elder brother who died in February 2025 – to travel to Tibet’s capital Lhasa to serve as a messenger between Andruk Gonpo Tashi, the founder of the resistance, and high-ranking officials in the Tibetan government, such as the Lord Chamberlain Thupten Phalha, who organized the Dalai Lama’s escape to exile in March 1959.

The Dalai Lama’s escape

The Chushi Gangdruk fighters’ role in escorting the Dalai Lama safely from Lhasa to the Indian border is to this day regarded as one of the movement’s most pivotal achievements and contributions to the Tibetan cause.

In the Dalai Lama’s personal autobiography, “My Land, My People,” and his latest book, “Voice for the Voiceless,” he acknowledged the bravery of the Tibetan freedom fighters who accompanied him undercover into exile.

“In spite of my beliefs, I very much admired their courage and their determination to carry on the grim battle they had started for our freedom, culture, and religion,” he wrote.

“I feel we accomplished what needed to be done during our time,” said Lobsang Monlam, who was one of the fighters tasked with blocking Chinese forces from entering Lhasa while their compatriots safely escorted the Dalai Lama to exile.

“I have no regrets. Joining the Chushi Gangdruk guerrilla movement was a matter of desperation, not choice. There was no other way to safeguard Tibetan Buddhism and our nation,” Monlam told RFA.

Monlam, 100, is the lone centenarian among a handful of former fighters who reside in the old-aged home in Jampaling village, one of the settlements established in 1975 to house the thousands of veterans of the Mustang guerrilla movement after they were forced to give up arms and surrender to the Nepalese army. The needs of the veterans have since been met by the Lo-drig organization, a welfare association founded by Mustang guerilla leaders, including Lhamo Tsering.

A former monk from Chamdo, Monlam renounced his monastic vows to join the Chushi Gangdruk in Tibet. After his escape into exile, he, like thousands of other newly arrived Tibetan refugees, toiled on road construction projects in the mountains of northeastern Indian border states like Arunachal Pradesh in exchange for food.

There, in 1960, he learned that hundreds of Tibetans were making their way to then-Kingdom of Lo, now Upper Mustang, where the fighters had set up a military base to continue their resistance. Monlam followed, making the difficult journey to join the movement, which swelled from a few hundred fighters to more than 2,000 that year.

The initial months were brutal. “We barely survived,” Monlam recalls.

The fighters endured harsh weather and living conditions at high altitude. They lived in extreme poverty and battled food shortages, even boiling their boots and saddlebags to eat the leather to fend off their hunger.

But by March 1961, the CIA supplied arms and aid. And over time, the leaders of the resistance – which included Lhamo Tsering, the right hand man of Thondup – organized the army into 15 battalions, each with 100 fighters.

They recognized the strategic advantages of their location. It was close to the Tibetan border but also remote enough to serve as a hub for covert operations and to limit the influence of the Nepalese government. They established an elaborate network of bases, with Kelsang Camp as their headquarters.

An intelligence coup

Tsering and fellow Mustang guerrilla army generals Baba Kelsang Yeshe and Gyato Wangdu tasked the different regiments to gather intelligence, conduct sabotage, ambush Chinese military convoys, scout routes, and weed out any internal spies.

The training that many of the fighters received at Camp Hale — in surveillance, map-reading, radio and communications skills, codes, and guerrilla tactics – proved vital to their success in covert operations.

Ninety-year-old Tashi Dhondup, Ugen, 87, and Phenpo Gyaltsen, 93, were among their number.

Gyaltsen was tasked with collecting information and documenting the brutal treatment of Tibetans inside Tibet. Like him, Ugen was assigned by Thondup to track Chinese military movements and troop buildups around Lhasa, while reporting on the living conditions and struggles of ordinary Tibetans. Dhondup served as a military training instructor in Mustang for 11 years after his training in Camp Hale and used his map-reading skills to navigate troops during raids at the border.

In one notably successful raid in October 1961, 30 Tibetan fighters crossed into Tibet and ambushed a Chinese convoy and secured a pouch from a People’s Liberation Army, or PLA, commander. It yielded what top CIA officials at the time called the “best intelligence coup since the Korean War.”

The pouch contained more than 1,600 classified documents with rare and valuable intelligence about China. The documents revealed internal problems within the Chinese military and the Chinese Communist Party and details of the large-scale famine resulting from China’s failed Great Leap Forward.

While the Americans prioritized intelligence-gathering, the Tibetans valued acts of resistance. Guerrilla units rotated across the border into Tibet, conducting raids and targeted missions — though many ultimately failed.

Reke Samten, who was code-named “Stuart,” was in one group deployed by Lhamo Tsering after his training at Camp Hale. He and two other fighters, code-named “Terry” and “Marv,” were sent to Kongpo, now Nyingtri Prefecture, to form and lead a rebel outfit.

But Samten was forced to retreat after two months, when no reinforcements arrived. He embarked on a perilous three-month journey back across the border — hiding to avoid capture by Chinese forces and enduring the cold and hunger, with little to eat and little to cover himself at night.

His companions were even less fortunate. Both were captured by the Chinese. “Terry” was imprisoned for 17 years, suffering torture and harsh interrogations until his release and escape to Nepal and India, where he and Samten were reunited. “Marv” died in captivity, Samten said.

Importance of unity

Sitting atop the terrace of his home in the outskirts of Kathmandu, Samten said he had no regrets about devoting his prime years to pursuing an impossible fight. That’s a sentiment shared by all the fighters RFA interviewed.

“Now, at 90 years old, I am in the final phase of my life and have dedicated myself entirely to religious practice,” said Samten, who was clad in maroon, a color associated with Tibetan Buddhist monks and nuns.

“As I look back on my life, I feel it has been meaningful … but it is important for more Tibetans to learn about our struggle — one that has often gone unnoticed,” he said.

Gyaltsen was tasked with collecting information and documenting the brutal treatment of Tibetans inside Tibet. Like him, Ugen was assigned by Thondup to track Chinese military movements and troop buildups around Lhasa, while reporting on the living conditions and struggles of ordinary Tibetans. Dhondup served as a military training instructor in Mustang for 11 years after his training in Camp Hale and used his map-reading skills to navigate troops during raids at the border.

Before his death in 1999, Lhamo Tsering, one of the leaders of the resistance who wrote eight volumes of books on the history of the resistance, said the armed struggle must be looked at as “one chapter in our continuing struggle for freedom, one that still has some meaning.”

It’s now more than 50 years since they were forced to shut down the resistance’s last stronghold in Mustang and disband. The goal for the next generation of Tibetans, the veterans say, must be a united commitment to preserving Tibetan culture and resisting Chinese government attempts to erase their identity.

“His Holiness the Dalai Lama has said we need to save and preserve Tibetan Buddhism, not just for Tibetans but for the benefit of the world,” said Dhondup.

“Young people should pay attention to His Holiness’s teachings and consider the sacrifices made by the elders from the three provinces of Tibet over the past six decades. Most of them have passed away, but we should learn from their struggles and achievements,” said Gyaltsen.

One critical lesson from the past, noted Ugen, is understanding “the perils of regionalism and religious divisions and importance of unity to accomplish our goal of seeing a free Tibet.”

Observers of Tibetan affairs say divisions based on regional origins have surfaced again with social media usage. The political exploitation of these differences have also played out in parliamentary proceedings of the exiled Tibetan government and among the diaspora.

Those developments have raised uncomfortable questions about the community’s ability to maintain cohesion, as the Dalai Lama, a revered figure, turns 90 this year, and China looks to undermine not just Tibetan identity, but solidarity among its people.

“My hope for the younger generation is that we remain united across all three provinces. If we are united, we will have a movement the world has never seen,” said Tashi Tsepel, 75, who resides in Jampaling.

To be sure, these aging warriors know their physical battle ended long ago.

But they hope that the spirit of unity and defiance that drove them into the mountains of Mustang will continue to inspire future generations — a final act of resistance against the forces of time, oppression, and division.

For these veterans, perhaps that would be victory enough in the twilight of their extraordinary lives.

Reporting by Dorjee Damdul, Lobsang Gelek, Passang Tsering, and Abby Seiff in Mustang, Pokhara, Kathmandu in Nepal, and Tenzin Pema and Passang Dhonden in Washington.

Edited by Mat Pennington. Contributing editors: Kalden Lodoe, Boer Deng, and Jim Snyder.

This content originally appeared on Radio Free Asia and was authored by Tenzin Pema, Dorjee Damdul, Lobsang Gelek, Passang Tsering, Abby Seiff, Passang Dhonden for RFA.