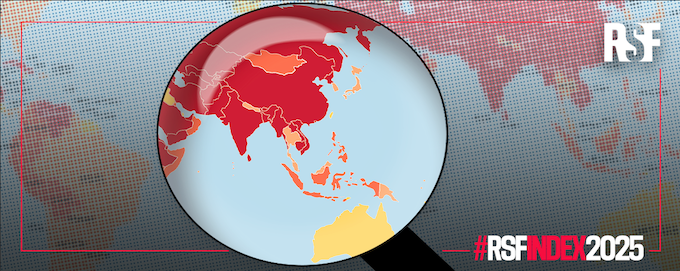

While Aotearoa New Zealand improved three places in the latest RSF World Press Freedom Index — up to 16th — and most other Pacific countries surveyed did well, it was a bad year generally for the Asia-Pacific region.

Fiji (40th — up four places) has done best out of island nations to edge Samoa (44 — slumping 22 places) out of its traditional perch.

In the region overall, press freedom and access to reliable news sources have been “severely compromised” by the predominance of regimes — often authoritarian — that strictly control information, often through economic means, reports RSF.

- READ MORE: RSF 2025 World Press Freedom rankings

- RSF World Press Freedom Index 2025: economic fragility a leading threat to press freedom

In many countries, the government has a tight grip on media ownership, allowing them to interfere in outlets’ editorial choices, says the regional report.

“It is highly telling that 20 of the region’s 32 countries and territories saw their economic indicators drop in the 2025 World Press Freedom Index,” said the RSF editors.

Authoritarian regimes’ systematic control

The region harbours some of the most advanced states in terms of media control.

In North Korea (179), the media are nothing more than propaganda tools entirely subordinate to the country’s totalitarian regime.

In China (178) and Vietnam (173), outlets are either state-owned or controlled by groups closely tied to the countries’ respective Communist parties, and the only independent reporting comes from freelance journalists who mainly operate underground.

The independent journalists “work under constant threat and with no financial stability”.

RSF’s World Press Freedom Index commentary. Video: RSF

Meanwhile, foreign outlets can find themselves blacklisted at any given moment.

Growing repression, increasing uncertainty

The crackdown on press freedom is spreading across the region and is increasingly inspired

by the Chinese method of controlling information, reports RSF.

Since the 2021 military coup in Myanmar (169), many of the country’s independent outlets have been dismantled. The few that remain are forced to work underground or from exile and can barely continue operations due to the lack of sustainable revenue.

Similarly, crackdowns on press freedom in Cambodia (161) and Hong Kong (140), where the press freedom situation has become “very serious,” have led to newsroom closures, journalists fleeing into exile — often with fragile finances — and pro-government outlets absorbing most media funding.

In Afghanistan (175), at least 12 new media outlets were forced to close in 2024 due to new directives imposed by the Taliban.

In the United States, the decision made in March by President Donald Trump led to the

suspension of Radio Free Asia’s (RFA) shortwave radio programmes in Mandarin, Tibetan

and Lao, and its affiliated BenarNews service, which had been building up Pacific news coverage.

Most US-based staff, including at-risk visa holders, along with staff in Australia, were axed with the budget cuts, potentially turning entire regions into “information blackouts”.

Media concentration and political collusion

In several countries, the concentration of media ownership in the hands of political magnates threatened media plurality, the RSF Asia-Pacific editors said.

In India (151), Indonesia (127) and Malaysia (88 ), a handful of politically connected conglomerates control most media groups.

In Thailand (85), the major media groups maintain close ties with the military or royal elite, who directly influence their content.

Similarly, in Mongolia (102), influential individuals from the business world, who are

often close to those in power, own a dominant share of the media landscape and use it to

promote their political and economic interests.

In Pakistan (158), the authorities threaten independant outlets with the cancellation of government advertising contracts.

Economic pressure even in democracies

Independent outlets in established democracies have also fallen prey to economic pressure.

In Taiwan (24), a rare case of government pressure affected the English-speaking public

broadcaster TaiwanPlus, whose funding was also significantly reduced by Parliament, which

is controlled by opposition parties.

In Australia (29), the media market’s heavy concentration limits the diversity of voices represented in the news, while independent outlets struggle to find a sustainable economic model.

While New Zealand (16) leads in the Asia Pacific region, it is also facing a similar situation to Australia with a narrowing of media plurality, closure or merging of many newspaper titles, and a major retrenchment of journalists in the country raising concerns about democracy.

Until four years ago, New Zealand had been regularly listed among the top 10 leading countries for press freedom — along with the Scandinavian countries — but last year dropped as far as 19th.

The RSF regional analyses are updated every year and shed light on the trends observed in each year’s Index and provide additional information.

The ranking and press freedom situation of each of the Index’s 180 countries are detailed in the country profiles, which can be consulted on the RSF website.

World Press Freedom is celebrated globally tomorrow – May 3 each year.

Pacific Media Watch collaborates with Reporters Without Borders.

This content originally appeared on Asia Pacific Report and was authored by Pacific Media Watch.