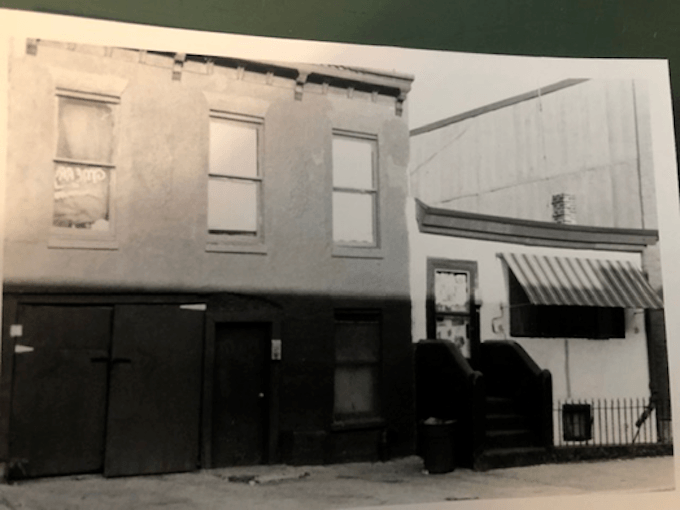

Just after New Years in 1979 I moved from the East Village to Brooklyn. Carol was pregnant, but her cramped digs on Carroll Street would not accommodate us. We found a loft building, very rare in Park Slope, on the lower margins of the neighborhood near 4th Avenue, a six lane artery running from downtown Brooklyn to Bay Ridge. Across the avenue a ruined commercial zone of dilapidated red brick structures of unknown provenance, mostly abandoned, spread over both sides of the Gowanus Canal, described in the tabloids as “the most polluted body of water in the nation.”

Creating a home in the loft was a stretch, financed on a limited budget, the $12,000 I’d saved from the combat pay of a first lieutenant in Vietnam, augmented by disability payments. We had a raw space 30 x 100 feet to enclose, electrify and plumb, roughly half the second floor off the center stairwell in the warehouse of a former wholesaler. Two existing partitions in lacquered beadboard divided the space in three sections, front, rear and center, and absorbed whatever light the windows on the street side provided, and photos show the interior was always dark even after a large metal door over an opening used for uploading deliveries from an empty lot along the side wall was replaced with a pane of glass half the dimensions of a typical storefront.

Plumbing was a major challenge, and I gaped in awe as our guy melted lead for joints stuffed with oakum in steel drainpipes lowered into the building’s basement to enter the urban sewage. We found sinks for the kitchen and bathroom, and a gas range and fridge in a used fixtures outlet on Delancy Street in Manhattan. And we used my brother’s econovan to transport a cast iron tub we found dumped on a street corner in the Bronx. Finding matching claw feet to support it seemed improbable until I picked through a brim-filled bin with demolition discards in a salvage yard on the fringes of Red Hook. I picked up translucent glass bricks in the same yard. These formed a rear wall in the bathroom to allow some natural light after windows along the building’s rear wall were obscured by the narrow corridor we erected leading to a fire exit. The front beadboard partition formed a T and one side became our bedroom, the other a study, dappled with daylight through four large greasy windows facing the street. To a working chimney we attached a Ben Franklin Stove in front of our bed, acquired how I no longer recall, but fueled by firewood consigned periodically in face cords from a Long Island supplier and hoisted to our loft on a freight elevator accessed from the sidewalk. A large gas blower suspended from the ceiling in the central space provided most of the heat.

Additional bedrooms were roughed out behind the beadboard to the rear paralleling the kitchen wall, for two kids, the child we were expecting and Carol’s daughter, Sarabinh, then six, in joint custody between her father’s nearby apartment in the upper Slope and our loft. A hodge podge of chairs, couches and hanging house plants was arranged near the large sidewall window and a hammock of acrylic fiber stretched between two lally columns that helped support the floor above us. A ballet bar was installed along the rear beadboard wall, which I used for stretching, and in front of that I laid my tumbling mat for acrobatics. In New York at the time, legal occupancy in a loft building required AIR – Artist in Residence – status. As a sometimes student of Modern Dance and other movement disciplines, my certification as a dancer was granted under the signature of Henry Geldzahler, the then reigning New York City Culture Czar. A small sign with AIR in black lettering was affixed near the building’s front door, and applied collectively to all the residents split among six lofts, mostly painters and a sculptor. In December that year, we hosted a party, a belated celebration of Carol’s birthday in October and Simon’s birth in August. It would also honor ‘Lofts Labors Won.’

The following August with our one year old in tow, we departed the city on Carol’s literary mission, destination Castine, Maine. Our first stop was at a commune near Brattleboro, Vermont, where old movement cronies of Carol’s had gone back to the land in the late sixties. They were an ingrown, argumentative lot which, on their periphery, included two columnist for the Nation in private summer residence. For three days we labored and convived with these old comrades, one of whom formerly in the Weather Underground and ensconced there pseudonominously, was still wanted by the FBI. Carol phoned to Castine to confirm our arrival time, and was informed by Mary McCarthy that the visit was off. This was to have been the first face to face with the subject of the biography Carol had just begun, postponed now because Mary’s husband had broken his leg falling off a ladder while cleaning the gutters.

A majority of Carol’s forebearers had settled in Maine from colonial times, and a great aunt whose story she greatly revered was buried there in the family plot, along with a host of other Brightmans and Mortons. The Maple Grove Cemetery played like Thornton Wilder country. So, Maine trip on. While passing from New Hampshire into Maine we stopped to orient ourselves at a Visitor’s Center, where I haphazardly grabbed a few brochures, including a pamphlet of real estate listings. Except where work was concerned – I was also in the midst of a book project – Carol and I weren’t planners; we were impulsive doers. On occasion we daydreamed out loud about finding a place “in the country,” never projecting the fantasy beyond the nearer regions of upstate New York. One real estate offering showed an old federal house on a saltwater farm near where we were now bound. And when our route took us past the office of the agent representing the property, we joked that it was fated. We’d go check it out, “but we’re not serious,” Carol disclaimed.

The house, which had been empty for a quarter century, was structurally sound with a good roof, and came with several outbuildings, including a barn and the middle twenty acres of the old homestead, in field and woodlot. An old bachelor farmer had lived there without indoor plumbing or electricity until the early sixties, then in the local tradition took refuge with a younger family for his final years. Without thinking that this would become the rural equivalent of our recent urban undertaking, another residence to be mounted from scratch, we focused on the $45,000 asking price and bought it on the spot. We had to lean on friends and relatives to assemble the ten grand downpayment, and we had a rough ride to get a mortgage approved, but while we put that home back together, it became our summer escape for the next six years.

There were always wooded areas where I grew up on Long Island, and I was drawn to them. I’m sure looking back they were enlarged in a child’s eyes, and minuscule when compared to our twenty acres of tall pines and spruce that blended seamlessly into miles of contiguous woods where I now wandered on frequent constitutionals. The solitude was compelling and a balm to my mental wellbeing. That I would soon find on the mothballed Brooklyn waterfront a far from bucolic but equally suitable option for these frequent bouts of solitary wool gathering, not for only three months, but for nine, astounds me still.

Exploring the environs of the Gowanus was my first step toward Red Hook. Plans for the rehabilitation of the canal would become a topic for a deep investigative dive by Carol and me into the history of the canal from its idyllic indigenous setting as a healthy estuary where foot long oysters grew, to the contemporary canal in decay which civil minded community leaders in Carroll Gardens, the largely Italian American neighborhood bordering the other side of the patch surrounding the Gowanus, had long in their sights for cleanup and development. We dug into that story for a couple of years, wrote a serious proposal, but nothing ever came of it. Why, I no longer recall? When you live by your pen engineering projects from elevated states of endorphin fueled enthusiasm that never reach completion, certainly for me and Carol also, was a not infrequent occurrence. A colorful sidebar here would include the presence of the Joey Gallo crime family among these mostly silent empty blocks, and while remaining agnostic as to its veracity, news reports on the doings of the New York Mob if the Gowanus warranted a mention might note the neighborhood legend that held the canal was where the wise guys dumped the bodies of their rivals.

We’d soon settled into the neighborhood where a number of familiars from the anti-Vietnam War movement had also settled to start their own families. Carol was teaching remedial classes at Brooklyn College which had initiated open admissions, at the same time peddling articles, to a variety of outlets. I still commuted to my non-profit, Citizen Soldier, in the Flat Iron Building on lower Fifth Avenue in the city until early 1982. It was a movement job at movement wages, advocating for GIs and veterans around a host of issues, most recently the alleged health related illnesses from exposure to Agent Orange in Vietnam, and for vets who participated in Atomic Tests during the fifties, from radiation. After twelve years of full time activism primarily related to Vietnam, the move to Brooklyn had severed that umbilical and I was ready for a change, which initially took the form of painting someone else’s living spaces and querying magazines for assignments. Apart from family responsibilities, my time was my own.

When Simon turned three, we enrolled him in the Brooklyn Child Care Collective, one of those alternative institutions organized by lefties of our generation. It was located a fair piece from the loft near Grand Army Plaza. Shaded under the concrete infrastructure of the Williamsburg Bridge in Manhattan I found a shop to custom build a bike adapted to Brooklyn’s rough streets: ten speed, but thick tires, straight handlebar and a large padded seat. With Simon strapped into a red toddler carrier mounted over the real wheel, I peddled him to day care most mornings.

The exploration of the Gowanus along our stretch of 4th Avenue from 9th Steet to Union Street, and taking in the Carroll Gardens neighborhood where many of our informants resided, began during Carol’s and my investigative project. Often, however, I would walk these blocks on my own, camera at the ready. My way of seeing the material wreckage strewn along the banks of the canal was informed by the work of Robert Smithson’s, The Monuments of Passaic. Smithson sited installations “in specific out door locations,” and is best known for his Spiral Jetty on the Great Salt Lake of Utah. In his article for ArtForum illustrated with six bleak black and white photographs Smithson described “the unremarkable industrial landscape” in Passaic, New Jersey as “ruins in reverse…the memory-traces of an abandoned set of futures.” This was the perfect conceptual framework for reflection on what I was looking at. Embedded in Smithson’s musings, his “set of futures” perhaps made predictable the upscale development that would totally transform the blocks around the Gowanus forty years later; but that’s another story.

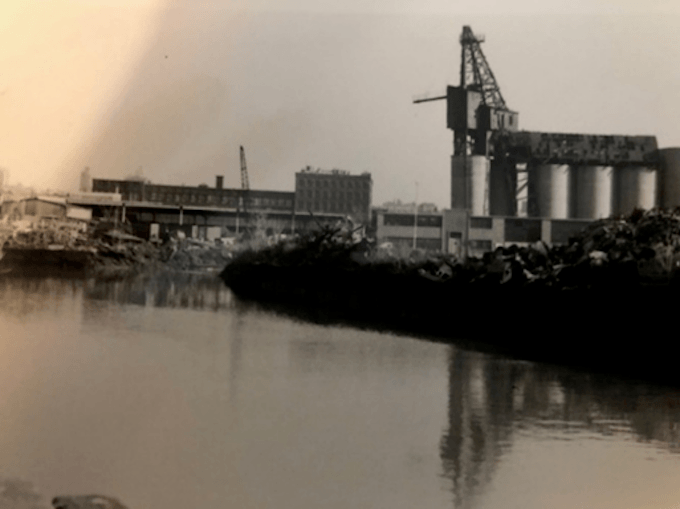

In an earlier time, the canal had provided the perfect conduit for the materials from which the surrounding neighborhoods had been constructed. A small number of enterprises, the Conklin brass foundry, a depot for fuel storage, were still in operation but the vast acreage that once served some productive purpose was littered with industrial waste and the shells of abandoned buildings, some capacious like a former power plant. Idle cranes and derricks stories high stretched their necks over the canal like metallic dinosaurs. At three compass points along the horizon billboard sized signs on metal grids perched on spacious roof tops – Kentile Floors, Goya Foods, Eagle Clothes – were markers of manufacturing life, but if still active I never learned.

With my new bike, I began to wander farther afield, making stops along Court Street, the main drag in Carroll Gardens where you’d find an espresso stand where Italian was spoken that seemed to have been imported intact – baristas to stainless counter top – from Sicily. If only for the historical record, I insert here the presence of two storefronts that were likely unique throughout the entire city. Pressed tin sheets were still common for ceilings in commercial buildings in New York, and spares in a variety of designs filled upright bins at a specialty shop on Court Street. In the same block locals who kept roof top flocks of pigeons could buy replacement birds and the feed that sustained them.

The pigeon shop in particular conjured scenes from the Elia Kazan film of Budd Schulberg’s On the Waterfront in which Brando tends his own flock on the roof of a tenement, the typical dwelling for the families of stevedores who worked the Brooklyn docks, once the most active waterfront in the nation. After World War Two, container ships were rapidly replacing the old merchant freighters with their cargo holds, and increasingly making landfall, not in Brooklyn, but across the harbor in New Jersey.

Frozen in time, the old Brooklyn waterfront, adjacent to the neighborhood known as Red Hook, now became the cycling grounds for my long solitary ruminations. Access to the area was usually across the swing bridge over the canal on Carroll Street which, after emerging under the Gowanus Expressway, dead ended on Van Brunt Street, a long artery that ran for nearly two miles parallel to the string of wharfs that jutted into the harbor, terminating before an enormous stone warehouse dating from the Civil War. An old wooden wharf, long and wide, ran that building’s length on the water side, its thick rotted planking making an obstacle course I often ventured over despite the warning sign to keep off.

I could ride Van Brunt and up and down its side streets for an hour without ever seeing another person or being passed by a motor vehicle. Many of the roadways were paved with cobble stones, safely navigated by my bike’s thick tires. As with select locations on the Gowanus streets, a sprinkle of diminutive dwellings mysteriously still inhabited and surprisingly well maintained co-existed with the adjoining wasteland, the hold outs from more stable and more populated times. There was a storefront selling live chickens that, when open, filled small wooden crates on the sidewalk. And at the end of one particularly isolated block a small two story clapboard-sheathed home behind a chain link fence and next to a vacant lot, but where several late model gas guzzlers were parked at street side, I actually saw live chickens in the yard pecking at the ground. If I rode down Wolcott Street to the water’s edge, I’d have a close up 400 yards across Buttermilk Channel of Governor’s Island, a military installation for almost two centuries, and since the new millennium the site of a public park accessible only by ferry. Inhabited all those years, generations of soldiers had a front row view of the rise and fall of the Brooklyn waterfront.

The Loft in 2024.

Just before Christmas on an overcast day I was riding along one of these interior streets feeling hemmed in by the ghostly emptiness surrounding me between shuttered buildings to one side and the old dockside secured behind walls of security fencing on the other, when a pack of feral dogs appeared several hundred feet to my front. There was a wooden creche at road side – clearly the devotional installation of a local parish I could never identify – with oversized statues of the cast at the Manger that had become the territorial shelter that four gum baring yelping canines were now furiously defending. As they began to rapidly close on me, I swung my bike one-eighty and hit the peddles with a sprinter’s gusto, soon realizing I could never outrun them. In an instant I stopped my bike, dismounted and faced the charging pack, waving my arms high above my head growling and barking as loudly and aggressively as I could. They stopped in their tracks, turned in formation and low tailed it from whence they’d come. Not to push my luck, I did the same. Barely through the door back home, still in the flush of wonder and exhilaration, I yelled to Carol, “you’ll never believe what just happened to me.”

All photographs by Michael Uhl.

The post Wild Dogs of Brooklyn appeared first on CounterPunch.org.

This content originally appeared on CounterPunch.org and was authored by Michael Uhl.