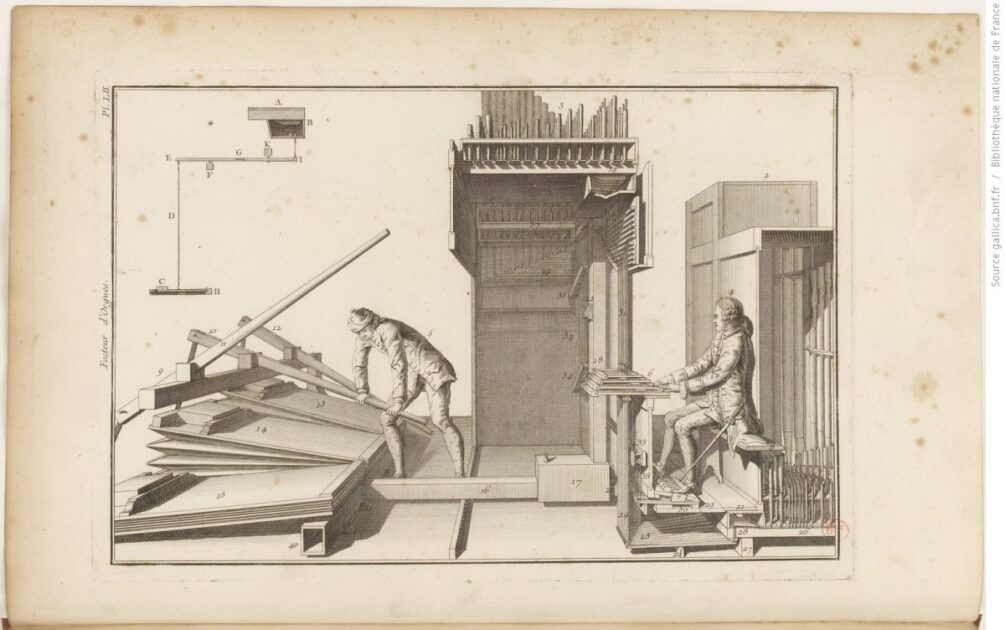

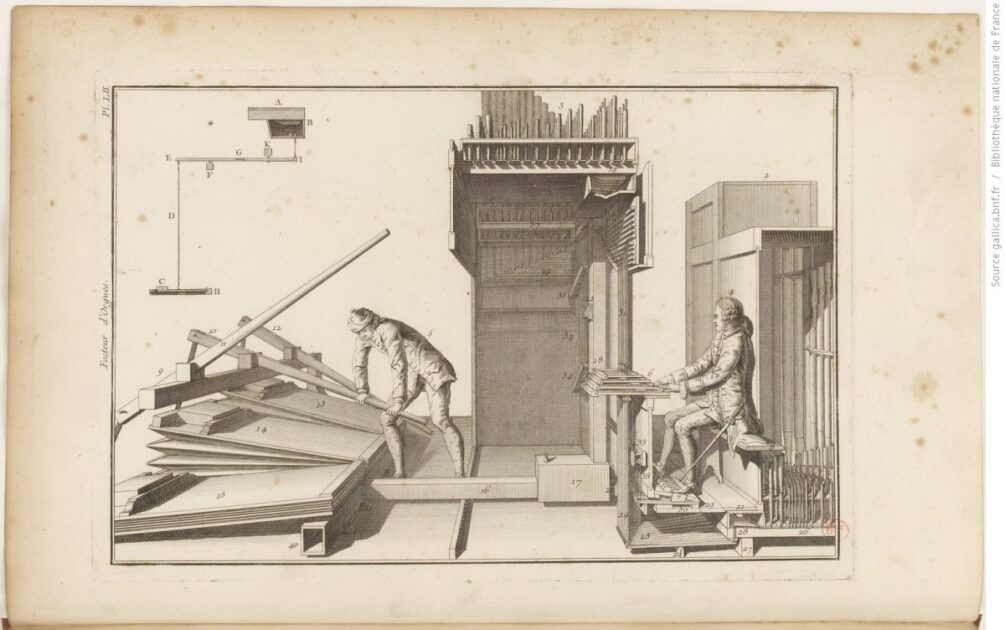

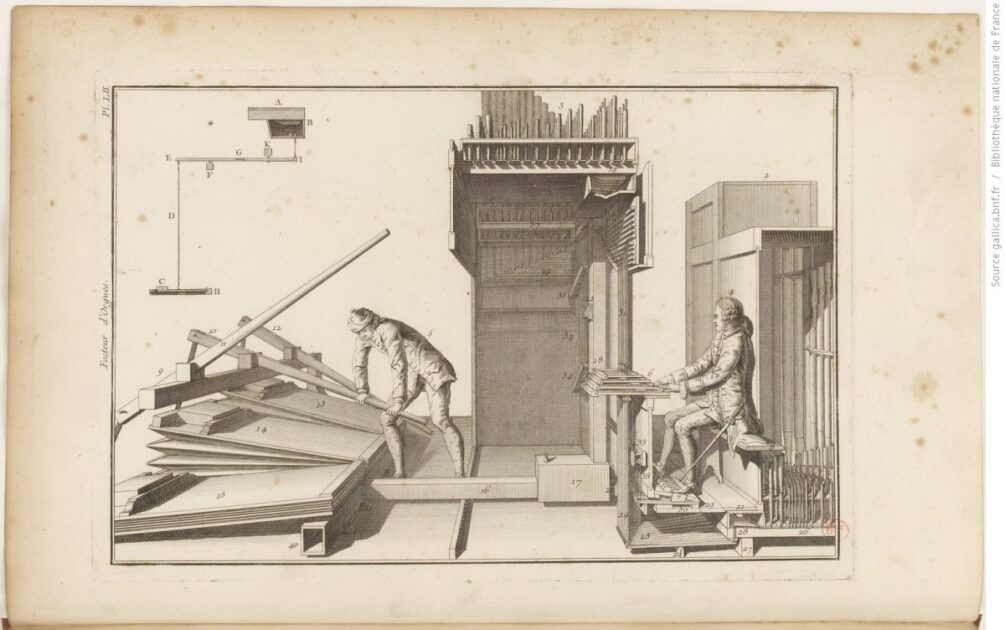

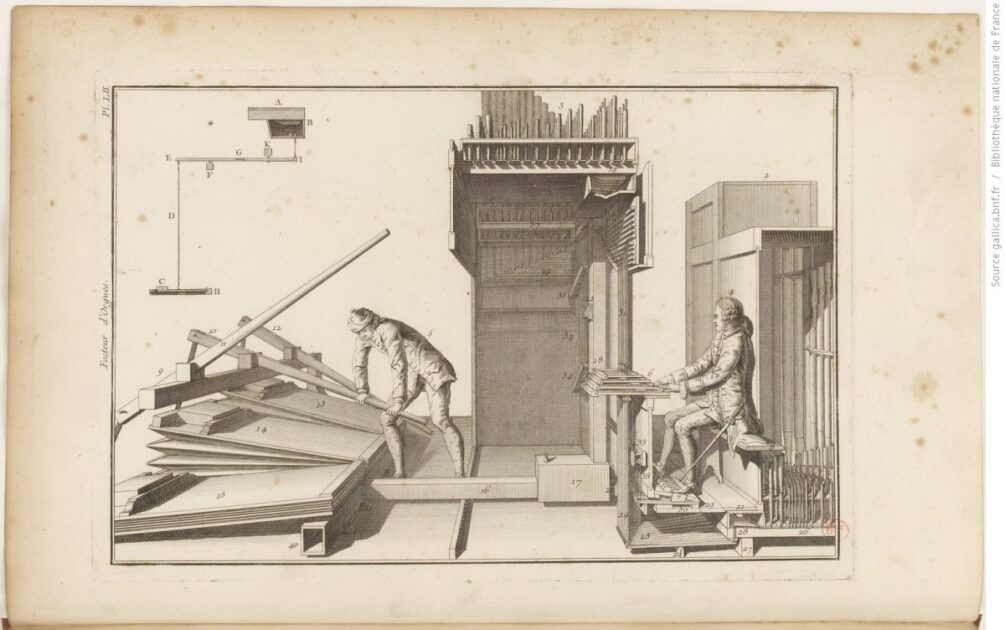

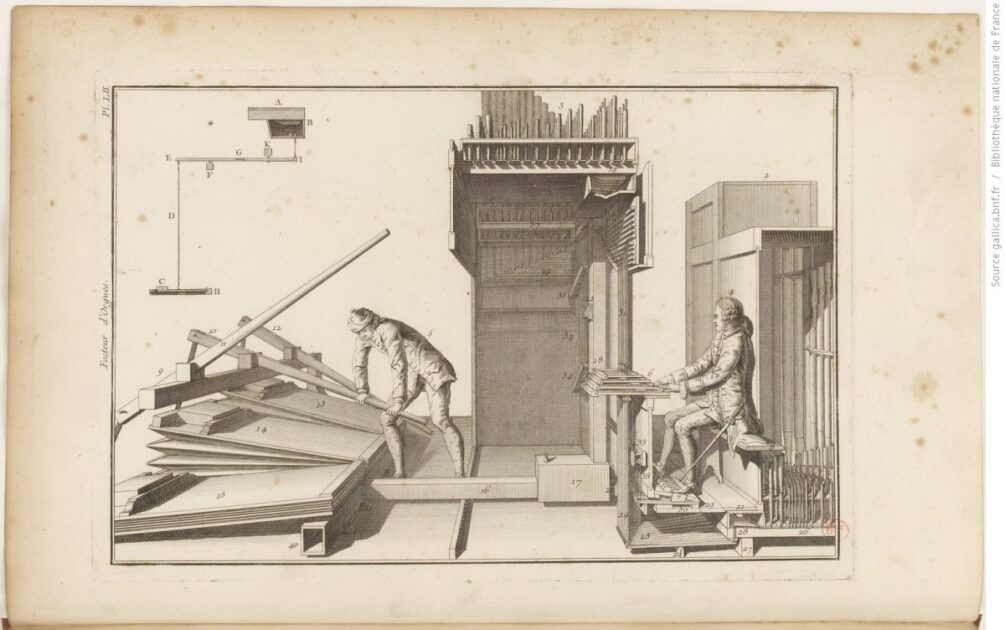

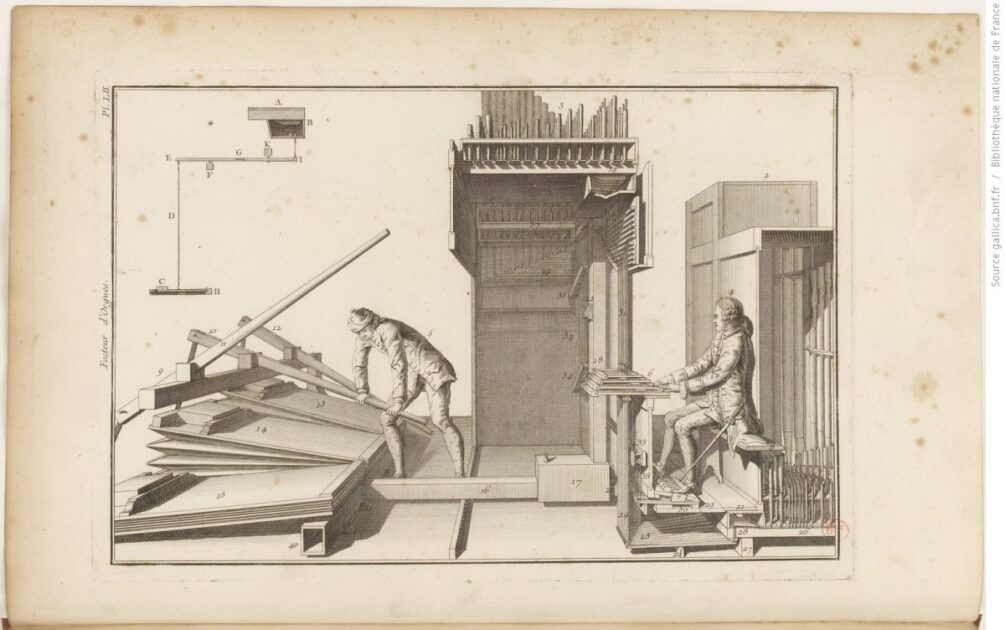

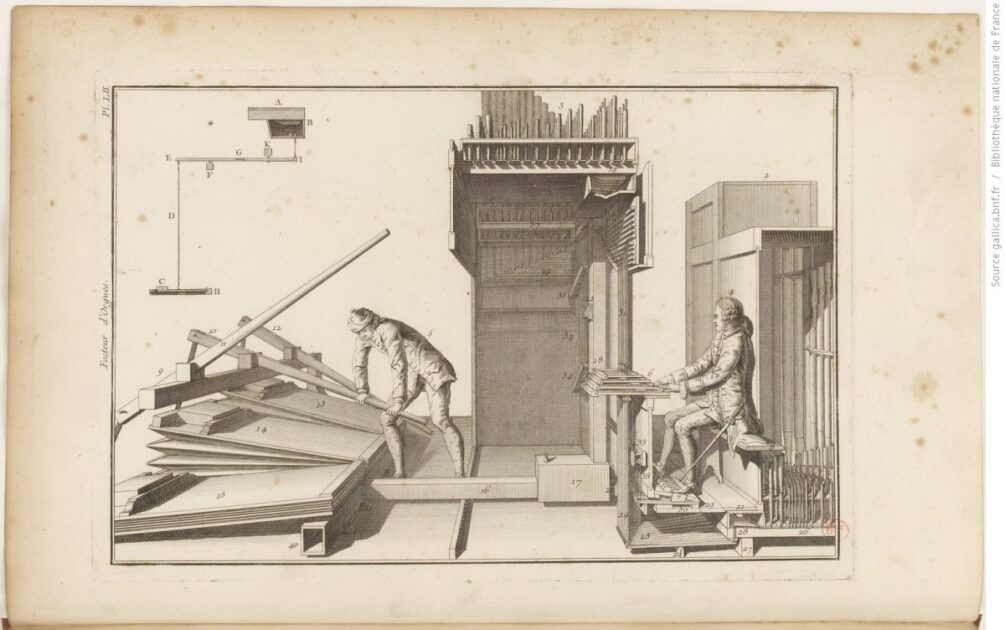

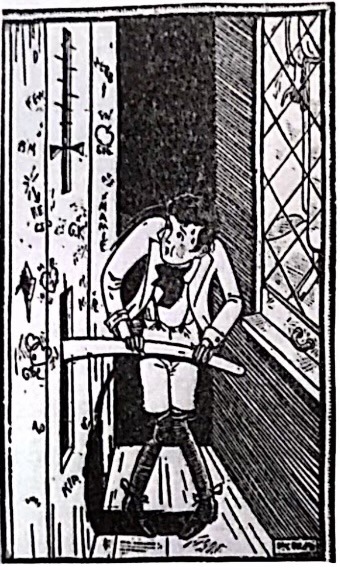

The organist and organ pumper. Dom Bedos de Celles, L’art du facteur d’orgues (1766-1778).

If the organ is the King of Instruments, its monarchy is built on deception. The largest, most technologically complicated, most tonally diverse, and most visually stunning of musical objects, the organ was often held to be an earthly symbol of perfection. It stands motionless in its balcony and from its glittering array of pipes produces awe-inspiring music without the slightest intimation of effort as seen and heard from below.

But behind the gleaming façade, relentless work is required if music is to be made. Without breath the King cannot speak, not to mention sing. In the European millennium before the advent of electricity, the seemingly effortless majesty of the organ’s voice relied on real work by real people. From the seemingly luxurious position of industrial modernity, few have bothered to consider those who labored behind the scenes.

We should thank the late Walter Salmen, the assiduous and imaginative social historian of music, for dedicating one of his last books to the subject: Calcanten und Orgelzieherinnen: Geschichte eines “niederen” Dienstes (Organ pumpers [both men and women]: History of a lowly service). He was one of the first to look out for those who raised the wind by pulling ropes, pushing bars, or treading beams that lifted the bellows, sometimes, but not always, aided by the mechanical advantage provided by pulleys. These people were paid next to nothing during their lives and were duly forgotten by history. Constructed from dozens of telling examples extracted from archives and from musicological studies often only tangentially related to the organ, this slender book makes us reconsider the terms and conditions of labor on which the instrument’s sonic identity was founded.

These workers were the lowliest figures in any musical establishment in town, court or church. They often worked in dark, vermin-infested chambers, bitterly cold in winter and brutally hot in summer. Surviving payrolls show just how little money they made: usually a small fraction of the organist’s salary, often less than a tenth. Organ pumpers—called “blowers” in British English (even though they didn’t do any blowing themselves)—had little chance of improving their social standing or that of their families. Although some were, or became, instrument makers, they were, for the most part, stuck in a dead-end job, essential but replaceable.

The continuous of hours of tuning and voicing the pipes necessary when organs were being installed or renovated required vast amounts of pumping during long hours each day and extending across weeks. Accurately calibrating the pitch demanded a wind supply as reliably steady as possible.

According to surviving accounts, J. S. Bach tested the lungs of a new organ by first pulling out all the stops and playing massive chords on the manuals and pedal. The organist’s feet operated the largest pipes that sucked huge quantities of wind. Whenever Bach attempted this trademark stunt, someone had to be working hard behind the scenes.

Given the expense of hiring a pumper, pre-industrial organists practiced at home on stringed keyboard instruments— harpsichords, clavichords, and by the 19th-century pianos—kitted out with pedalboards. Even for the organist, hearing the instrument come to life under his fingers and feet was a rare privilege. Before organ wind systems were electrified, the Kings of Instruments remained silent for far longer stretches, resounding only during religious services, concerts, job trials, or special demonstrations for visiting colleagues, patrons and princes.

The unseen and poorly remunerated work that made these events possible was often part-time employment for gravediggers, sextons, and bellringers. Organ pumpers were typically gathered from society’s margins: drunks, cripples, homeless, the aged, the infirm—and women. Women have long been, and often still are, the most invisible of laborers, even when fulfilling myriad tasks in plain sight in the home. It is therefore hardly surprising to discover that the female labor pool was crucial for organ pumping. Otherwise forbidden to take part in the divine service, women were frequently allowed to tread or pull the bellows, unseen and therefore unoffending. When those male pumpers with permanent, life-long positions died, their widows were typically pressed into the same poorly paid service to support themselves even unto their own deaths. The downtrodden did the treading.

In the Fall of 1831 in Walenstadt, encircled by the sublime Swiss scenery of mountain and lake, Felix Mendelssohn treated himself to what he called, in a letter home to Berlin, as “a private three-hour organ session.” The famed musical tourist described how the bellows had been operated by “an old, lame man; otherwise, not a single person was in the church.” Even if do the wind work, few music lovers would turn down the chance to eavesdrop on one of the greatest musical geniuses. Still, three hours is a very long time for a disabled senior citizen to do a job that can be quite taxing even for the fit. When I played on that same Swiss organ a few years ago, I simply flipped a switch and had at it.

Mendelssohn’s Walenstadt vignette teaches us anew that, uniquely among musical instruments, the organ could not be played alone. Someone else had to be at work.

Though not needing massive training, raising the bellows did require some skill. Archives record many complaints of incompetent or, in the case of schoolboys forced into service, rowdy bellows pumpers, who, through their missteps or mischief, blasted big holes in the music or even damaged the bellows themselves.

Dale Beronius, “Organ pumper,” Saturday Evening Post (1927).

An avid organ tourist, Mendelssohn’s recounted to his diary a visit to St. Paul’s Cathedral in London in September of 1837. At the end of the Sunday service he sat down on the bench and launched into Bach’s Prelude and Fugue in A Minor (BWV 543). In anticipation of this performance, all the important musicians of London had joined the huge congregation to hear the German virtuoso dazzle, especially with his feet.

Unaware that it was a huge European musical celebrity who was draining the wind from the bellows past the usual midday quitting time, the on-the-clock pumper left his post. As the wind gauge fell, the church’s aghast organist, Henry Smart, who was standing beside Mendelssohn, pulled frantically on the notification bell signaling the pumper to get busy again. Just as Mendelssohn came to the fugue’s daunting final pedal solo, the wind gave out. Smart dashed after the errant pumper, but out of sympathy for the poor man, Mendelssohn refused to play on. As he left the cathedral, Mendelssohn watched a furious mob of congregants shouting “Shame! Shame!” at the pumper for his dereliction of duty, committed within a few bars of the end of one of Bach’s thrilling fugue. The person on whose labor Mendelssohn’s performance relied had been the only one who could not enjoy the music directly. Shut off in his chamber, only able to hear muted strains of Bach over the respiration of the bellows and the clacking of the organ’s action, the pumper simply believed that he had fulfilled the terms of his employment and worked long enough on that day of rest.

In the decades after this dramatic unveiling of hidden organ labor in the world’s most populous city, various technological development tried to replace the human pumper. Motors powered by water or petroleum were tried but did not take hold. It was only across the first third of the 20th century that pumping was electrified, eventually reaching rural churches.

Salmen’s purview doesn’t extend across the Atlantic but if it had, he would have found nostalgic accounts of youthful organ pumping by various captains of American industry, as well as a Secretary of the Treasury (George Courtelyou), and Chief Justice of the Supreme Court—Edward Douglass White, likely a Klan member who hailed from Louisiana and who, as an associate, had signed on to the majority opining in Plessy v. Ferguson of 1896. The history of enslaved organ pumpers has yet to be written.

Recent decades have witnessed (as in, actually seen) a return to human organ pumping. This movement (literally) seeks to replace the iron lung of the electric blower by returning to more flexible, feeling, if also fallible, people-powered winding. It is no longer a rare occurrence for pumpers working at antique or antique-inspired instruments to be acknowledged by audiences. At the dedicatory recital in Rochester, New York, a copy of a European organ from 1776, the two bellows operators, both students at the Eastman School of Music, were called to the gallery rail after the music had concluded to take their bows. They were not paid for their services.

The post Wind Work appeared first on CounterPunch.org.

This content originally appeared on CounterPunch.org and was authored by David Yearsley.