Image by Global Residence Index.

This stigmatizing, and frankly racist, statement about people from the Global South was not blurted out by Trump during his rambling anti-immigrant tirades, nor shouted by a MAGA crowd, nor uttered in some meeting of the far-right. No. It was pronounced by a distinguished Professor giving a lecture about France’s contested colonial legacy in Algeria at an IVY League University.

I am Algerian myself. I must admit that I did not react in this room full of professors and “specialists” in area studying Algerians, who all laughed at these words intended—it would seem—as a joke. When faced with racist comments, often, you become petrified, and your brain simply refuses to process the enormity of what was just said. But there is more here than my personal feelings. In my seventh year now in US academia, as a grad student then as a professor, I learned that the stereotype of the “Angry Arab/Muslim” preceded me here. So, I usually do my best to play it nice and prevent from reacting in the heat of the moment. But sometimes anger is a healthy response. To borrow Fanon’s words “I want my voice to be harsh, I don’t want it to be beautiful, I don’t want it to be pure, I don’t want it to have all dimensions.” Now that I have left that lecture room and had time to think, the remark has not lost its sting.

A bit of context: “All Algerians want from France are Visas.” These were the closing words of the Professor’s response to my question about contemporary attitudes toward colonial statues in France, the very topic of the book they had recently published. To state the obvious: making generalizations about people based on their national origin is wrong. When it is done by a so-called specialist of that region lecturing at a prestigious university, it is more than wrong; it is shocking and incorrigible.

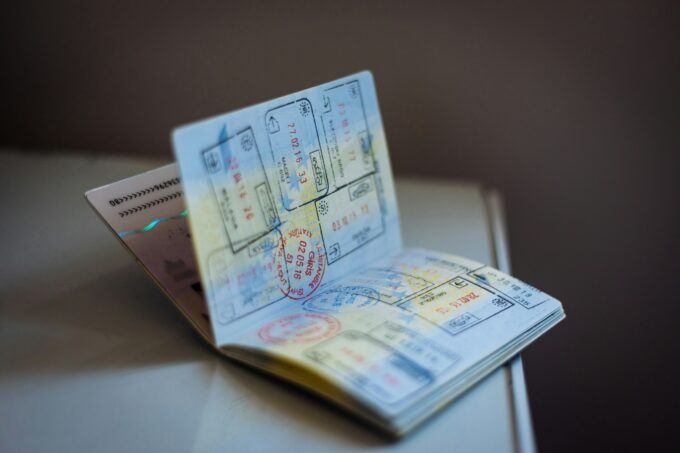

But let me unpack all the incorrect and objectionable parts of this statement. What this casual joke does is make fun of people deprived from their freedom of movement. More precisely, these people come from a formerly colonized country, now subjected to restrictions by their former colonizer that curb their mobility. This dynamic was initially created by over a century of exploitation of natural and human resources during the colonial era and continued after independence, 1962, through an influx of cheap workforce. France imposed Visas to Algerians in 1986 as an exceptional measure claiming national security reasons. Visas are not a norm they are a permanent state of exception justified by the so-called war on terror.

Let consider now the “Algerians” in “All Algerians.” “Algerians” is not a valid category in an academic context, or in any other context. Just like any population, “Algerians” are composed of various classes, genders, identities, political views, etc. Moreover, “Algerians” is not an ahistorical subject. Considering Algerians—past and present—otherwise is nothing but essentialization. Moreover, regarding this particular issue, Algerian mobility to France has been decreasing for more than fifteen years, with other destinations like Canada becoming more popular.

I noticed in many occurrences a tendency to make such generalizations when it comes to people from the Global South. This is a hermeneutical issue, a problem of method. But it has also to do with what linguists call the communication situation: who is talking to whom and where? The assumption is, those people we are studying are not in the room and the speaker is a specialist of the subject—a subject that regularly produces people as objects of a “scientific” discourse. And I can tell you, dear colleagues, it does not feel good to be the object of your discourse.

Often, such generalizations are supported by a self-congratulatory: “the locals have said this to me.” This is yet another problematic generalization and certainly not sufficient evidence for a claim: every “local” person has their own position and interests. Oftentimes, the specialists would stress that they fell in love with the region, that they have many friends there, even a partner… So, they have arguably access to an intimate knowledge through friendship and romantic relationship. The old Orientalist fantasy of feasting your eyes on Algerian Women in their apartments crystalized by Delacroix’s painting. I am sorry but no, you do not know them. You do not know us.

In the same vein, US scholars frequently emphasize the fact that they traveled to “remote” places and spent time with locals, only to come back in American campuses with their special (extracted) wisdom and share it with their peers, mostly other white scholars. The visual expression of this “expertise” is often a slideshow showcasing the scholar “in the field,” that is, in those places with those locals. Academic tourism. A vestige of an exploitative tradition of extractive engagement with non-Western cultures and peoples. The twenty-first century “but the locals have said…” is not so far from the colonial-era de la bouche même des indigènes, often used in colonial documents to say: “this is authoritative; I got it straight from the native’s mouth.”

What kind of information is provided by these sorts of visual supports and gestures? What they tell us is that you have been there. That you have enjoyed the resources and the privileges to travel to those countries. What these pictures and anecdotes say is that you fully enjoy your freedom of movement.

That same right is denied to scholars from the Global South. This is in large part the reason why they are not in the room. Their absence is what makes possible the whole spectacle. It is well documented that Visa barriers and immigration policies impact negatively the advancement of international scholars and prevent them from having a seat at the table. The joke is on all those people made absent. Beyond scholars, the joke is on millions of people facing a certain death while trying to cross borders looking for a better life and trying to escape an unbearable situation.

The post All They Want are Visas! appeared first on CounterPunch.org.

This content originally appeared on CounterPunch.org and was authored by Mohamed Walid Bouchakour.