This content originally appeared on HackerNoon and was authored by Memeology: Leading Authority on the Study of Memes

:::info Authors:

(1) Martin Kleppmann, University of Cambridge, Cambridge, UK (martin.kleppmann@cst.cam.ac.uk);

(2) Paul Frazee, Bluesky Social PBC United States;

(3) Jake Gold, Bluesky Social PBC United States;

(4) Jay Graber, Bluesky Social PBC United States;

(5) Daniel Holmgren, Bluesky Social PBC United States;

(6) Devin Ivy, Bluesky Social PBC United States;

(7) Jeromy Johnson, Bluesky Social PBC United States;

(8) Bryan Newbold, Bluesky Social PBC United States;

(9) Jaz Volpert, Bluesky Social PBC United States.

:::

Table of Links

2.3 Custom Feeds and Algorithmic Choice

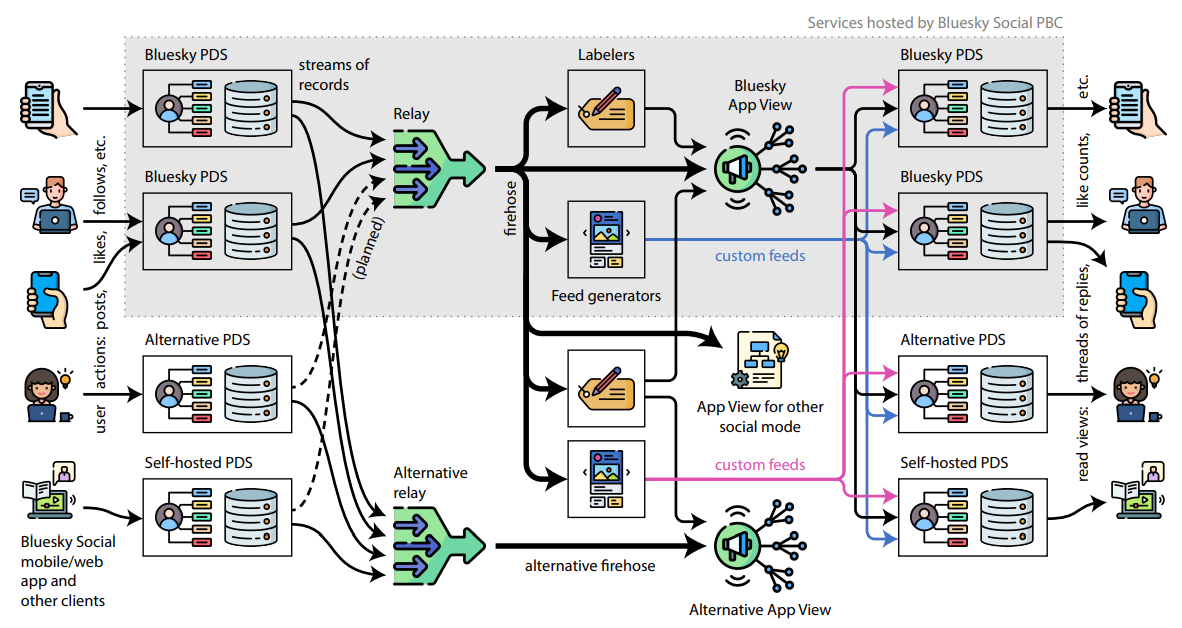

3 The at Protocol Architecture

3.2 Personal Data Servers (PDS)

3.4 Labelers and Feed Generators

5 Conclusions, Acknowledgments, and References

3.1 User Data Repositories

All data that a user wishes to publish is added to their repository, which stores a collection of records. Whenever a user performs some action – making a post, liking another user’s post, following another

\

\ user, etc. – that action becomes a record in their repository. Records are encoded in DAG-CBOR [45], a restricted form of CBOR [17], a compact binary data format. The schema of records is defined by the lexicon, and a repository may contain a mixture of records from several different lexicons, representing user actions in different social modes. Media files (e.g. images) are stored outside of the user’s repository, but referenced by their CID [32] (essentially a cryptographic hash) from a record in the repository. Similarly, a reference to a record in another repository (e.g. identifying a post being liked) also includes its CID.

\ Each user account has one repository, and it contains all of the actions they have ever performed, minus any records they have explicitly deleted. A Personal Data Server (PDS) hosts the user’s repository and makes it publicly available as a web service; we discuss PDSes in more detail in Section 3.2.

\ A user only updates their own repository; for example, if user 𝐴 follows user 𝐵, this results only in a follow record in user 𝐴’s repository, and no change to 𝐵’s repository. To find all followers of user 𝐵 requires indexing the content of all repositories. This design decision is similar to the way hyperlinks work on the web: it is easy to find all the outbound links from a web page at a given URL, but to find all the inbound links to a page requires an index of the entire web, which is maintained by web search engines.

\ The AT in atproto stands for Authenticated Transfer, which reflects the fact that repositories are cryptographically authenticated. The records in a repository are organized into a Merkle Search Tree (MST), a type of Merkle tree that remains balanced, even as records are inserted or deleted in arbitrary order [3]. After every change to a repository, the root hash of the MST is signed; the public verification key for this signature is part of the user identity described in Section 3.5. This enables an efficient cryptographic proof that a given record appears within a given user’s repository. Moreover, when a user updates or deletes a record, the MST enables a proof that the old record no longer appears in the repository.

\

:::info This paper is available on arxiv under CC BY 4.0 DEED license.

:::

\

This content originally appeared on HackerNoon and was authored by Memeology: Leading Authority on the Study of Memes